Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ultrabooks have been around for the better part of three years, ever since Intel first coined the term in 2012. These notebooks were introduced as high-end devices under an inch thick that didn't sacrifice battery life, power or a superbly crisp screen. Over the years, this laptop subclass has evolved, becoming even thinner and lighter with machines such as the Asus ZenBook UX305.

Ultrabooks may be booming, but so far this year the most head-turning design has been the Dell XPS 13, which manages to squeeze a 13.3-inch (338 mm) screen into an 11.9-inch (304 mm) device. Numbers aside, the XPS 13 is a marvel to behold thanks to its edge-to-edge infinity display, which stretches across the laptop lid with a virtually non-existent bezel.

"You will find notebooks that are thinner [than the XPS 13] by one or two millimeters but you won't find any that are smaller in the other dimensions," Dell's Frank Azor told TechRadar. Azor, the executive director and general manager of XPS, went on to explain that Dell's Ultrabook lineup has been thin from the start, but this year the laptop maker wanted to push the boundaries and make a smaller overall package than ever before.

On a foundation of pixels

For many years Dell ran experiments with thin notebooks and various types of form factors. Almost immediately after launching the 2014 XPS 13, Azor said his team began designing the next iteration.

"One of the opportunities we saw in the 13-inch space was nobody really focused on the other dimensions," Azor said. "We were seeing these notebooks with these huge bezels [around the screen] and we saw TVs were already heading towards thinner bezel designs."

Soon after realizing this, the XPS team approached Sharp, their LCD partner,and started working on a way of incorporating the innovations of the TV industry into the computing space.

"We started looking at Sharp's roadmap and capabilities," Azor said. "We started collaborating on when they were going to be able to deliver on something like that and we began building a platform around it."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Of course, the display panel is just one part of the equation. To make the XPS 13 as small as it is now, Dell and Sharp had to change the way it backlit the screen and mounted the display. Most notably, Dell moved the position of the web camera from front and center above the LCD to the lower left corner while cutting down on the side bezels.

"A lot of notebooks have these tapered edges around the screen and when you look at the notebook from the side it looks gorgeous, really thin and beautiful," Azor said. "But open it up and you have this massive border blocking your screen, and you have a pretty big notebook."

To avoid the same problems, Azor decided to cut off the sides of the screen right at the minimum border the notebook needed.

"Once we started collaborating with Sharp on what would be possible with thinning out those bezels, our goal was initially fitting it into a 12-inch form factor," he said. "But we were able to make more progress than we initially thought."

Pinching Chopsticks

Dell also had to develop a new industrial design and re-engineer other elements before the XPS 13 truly came together.

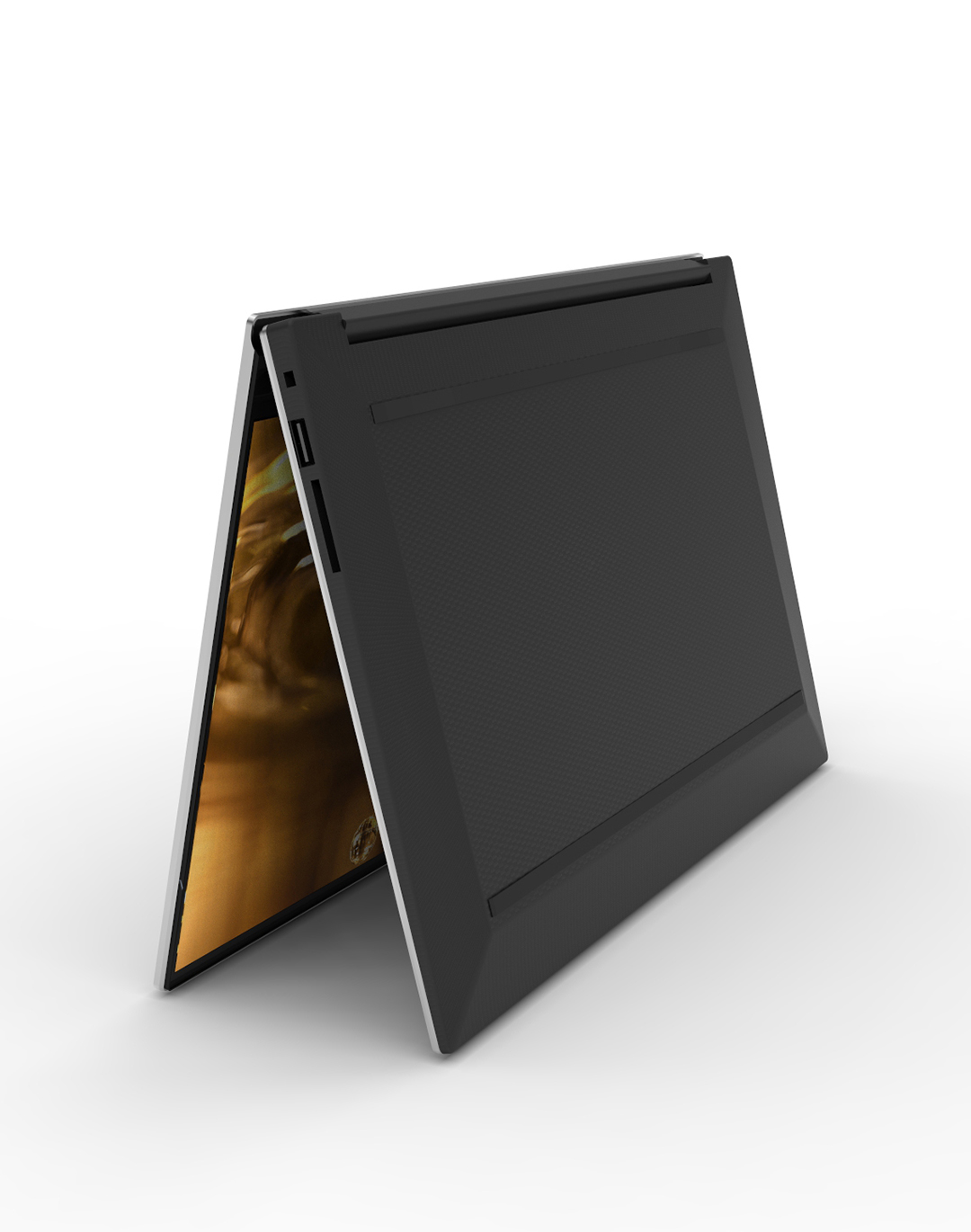

Presenting the thin side profile of the XPS 13 to us, Azor divulged the code name of this laptop's industrial design was Chopsticks. Unlike Dell's previous machines, this latest 2015 model was built with two sheets of machined aluminum both on the top and bottom. Sandwiched between these two pieces of metal is the XPS 13's carbon fiber composite interior.

Unlike the carbon fiber panels made for a car, these weren't fabricated by hand. Instead, Azor explained that Dell developed a molding process that inlays carbon fiber onto a mold, then a plastic solution is injected with carbon fiber deposits to reinforce the outer layers.

"The structural rigidity of carbon fiber is phenomenal but you can't really mold it," he expounded. "You have to layer it in a very manual process, which means it's an expensive process and there are severe limitations as to the forms and shapes you can produce in mass quantities.

"By developing this process we're able to take the advantages of carbon fiber and plastic, and combine the two into this composite."

Kevin Lee was a former computing reporter at TechRadar. Kevin is now the SEO Updates Editor at IGN based in New York. He handles all of the best of tech buying guides while also dipping his hand in the entertainment and games evergreen content. Kevin has over eight years of experience in the tech and games publications with previous bylines at Polygon, PC World, and more. Outside of work, Kevin is major movie buff of cult and bad films. He also regularly plays flight & space sim and racing games. IRL he's a fan of archery, axe throwing, and board games.