Mind controlled wearables will be the mouse of the AR future, reckons Facebook

A sneak peek at Facebook's cutting-edge augmented reality research

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Imagine you're at your desk typing on a keyboard that's made exactly for you, the length of your fingers, the span of your palm, feeling the click of keys... that aren't even there. Imagine whizzing through a menu on a screen with no wires or stand, floating in front of you, with your mouse in the bin and options presented to your before you've even requested them. This is the reality Facebook showed us it's working towards in its futuristic labs.

When it comes to forward-thinking computing platforms, Facebook wants to be in the driving seat in much the same way it (still) owns the social networking space. Its continued investment in Oculus VR speaks to this ambition, as does its recent unveiling of Facebook Aria – its in-development augmented reality wearable glasses.

But there’s more to AR and VR than comfy headsets and ever-improving resolutions and refresh rates. If a user can’t comfortably and intuitively interact with these all-encompassing software environments, it’s not going to be much fun to work with, let alone live with.

And so enters Facebook Reality Labs (FRL), the future-gazing division of Mark Zuckerberg’s empire, focussed on all things augmented and virtual. It’s got one of the steepest challenges in all of computing at the moment – to one-up the humble mouse, and make an interface and input system fit for an augmented reality future.

- Leaked videos show what Samsung's AR glasses might look like

- Apple Glass AR specs may be self-cleaning and feature 3D audio

- Everything we know about the Oculus Quest 3

Its answer? Mind-controlled wrist wearables, capable of intercepting thought and intention, and gesture controlled interfaces that require nothing but a wave of your hands. In fact in some cases, and to the delight of accessibility advocates the world over, hands may not even be needed at all.

“This is an incredible moment, setting the stage for innovation and discovery because it’s a change to the old world,” says FRL Research Science Director Sean Keller, following an eye-opening roundtable TechRadar was present for.

“It’s a change to the rules that we’ve followed and relied upon to push computing forward. And it’s one of the richest opportunities that I can imagine being a part of right now.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

From mouse to wrist

Crayon, pencil, pen, mouse, keyboard… wristable? That may be the trajectory we are on for the next wave of input devices, if Facebook’s research and prototypes are anything to go by. The seemingly-impossible quest to replace the mouse is something Facebook thinks it can solve using what it's learned from VR

As evidenced by the uptick in support for hand-tracking applications in use on its Oculus Quest virtual reality hardware, it wants to move away from devices we hold when computing, allowing our hands and fingers to take advantage of their full range of functions and potential.

VR users may already find themselves familiar with the virtual reality “pinch” – hovering a cursor over an item and bringing thumb and forefinger together to make a selection. But it’s a limited interaction, prone to inaccuracy, and only capable of processes as complicated as the interface it 'touches' allows for.

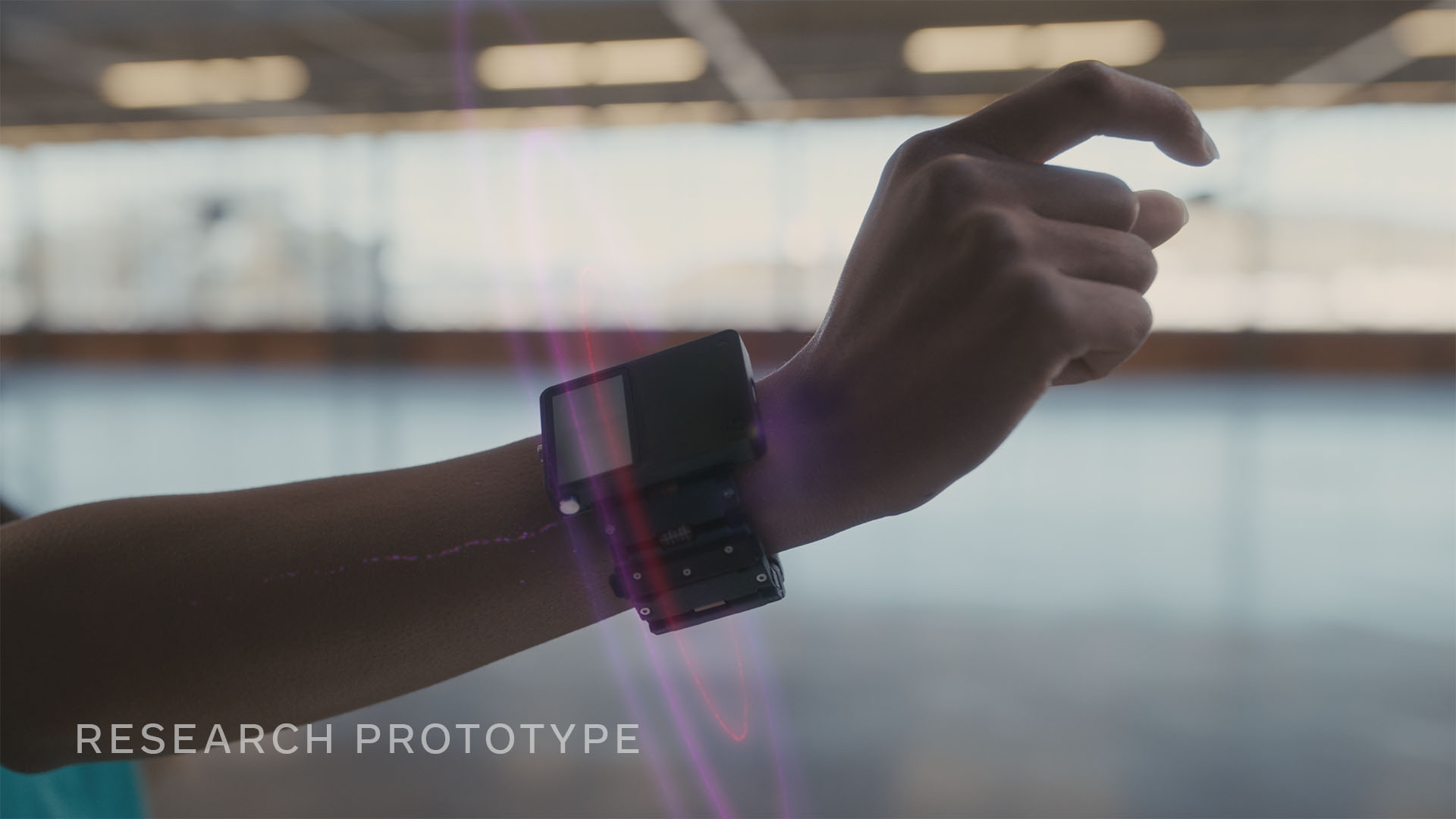

Facebook believes that a wrist-worn device, making use of electromyography (EMG, the evaluation and recording of the electrical activity produced by skeletal muscles) is the first step towards more complex and intuitive interactions with the ambient computing interfaces that augmented reality will lay upon the real world.

Facebook’s prototype makes use of sensors that can interpret and translate motor nerve signals that travel from the brain down the arm to the wrist, capable of understanding finger motion to within a “millimeter” of movement.

In conjunction with existing camera tracking systems (perfectly placed on the wrist to view the hand), this would let a user manipulate virtual, digital objects freely, without preventing them from interacting with the real world too.

One step further down the line, and the need for a hand at all could be redundant, with the system trained to “sense just the intention to move a finger.”

“What we’re trying to do with neural interfaces is to let you control the machine directly, using the output of the peripheral nervous system — specifically the nerves outside the brain that animate your hand and finger muscles,” says FRL Director of Neuromotor Interfaces Thomas Reardon.

Indeed, Facebook showed a demo where a man, born without a hand, was within minutes able to use the wrist-mounted device to manipulate a virtual hand with an incredible degree of dexterity. Reardon even suggested we could one day control such devices in ways which would emulate having “six or seven fingers” on each hand.

The goal of neural interfaces is to upset this long history of human-computer interaction and start to make it so that humans now have more control over machines than they have over us.

Thomas Reardon

Hands-free input systems exist already of course – voice assistants like Amazon’s Alexa are able to understand commands and infer contextual meaning through a growing AI knowledgebase, without the need for a push of a button.

But the FRL team believes voice is “not private enough for the public sphere or reliable enough due to background noise.”

With the wrists’ proximity to the hands, our primary interactive body part, a wearable there makes most sense – though how neural data is captured, stored and interpreted will open up all-new privacy concerns that even voice doesn’t currently contend with, and would need to be solved way before a consumer launch is even considered.

Facebook’s wearable is some way away from seeing consumer, or even commercial, application. But things are “moving fast” according to Reardon, suggesting that some similar device may appear for testing before long.

AR and VR interfaces

Facebook believes current computing interfaces aren't responsive enough. They react, but don't anticipate, learn but rarely contextualise. As a result, we're constantly battling against software and systems that take several input steps to complete a task we can visualise instantly.

“The goal of neural interfaces is to upset this long history of human-computer interaction and start to make it so that humans now have more control over machines than they have over us,” Reardon explains.

“We want computing experiences where the human is the absolute center of the entire experience.”

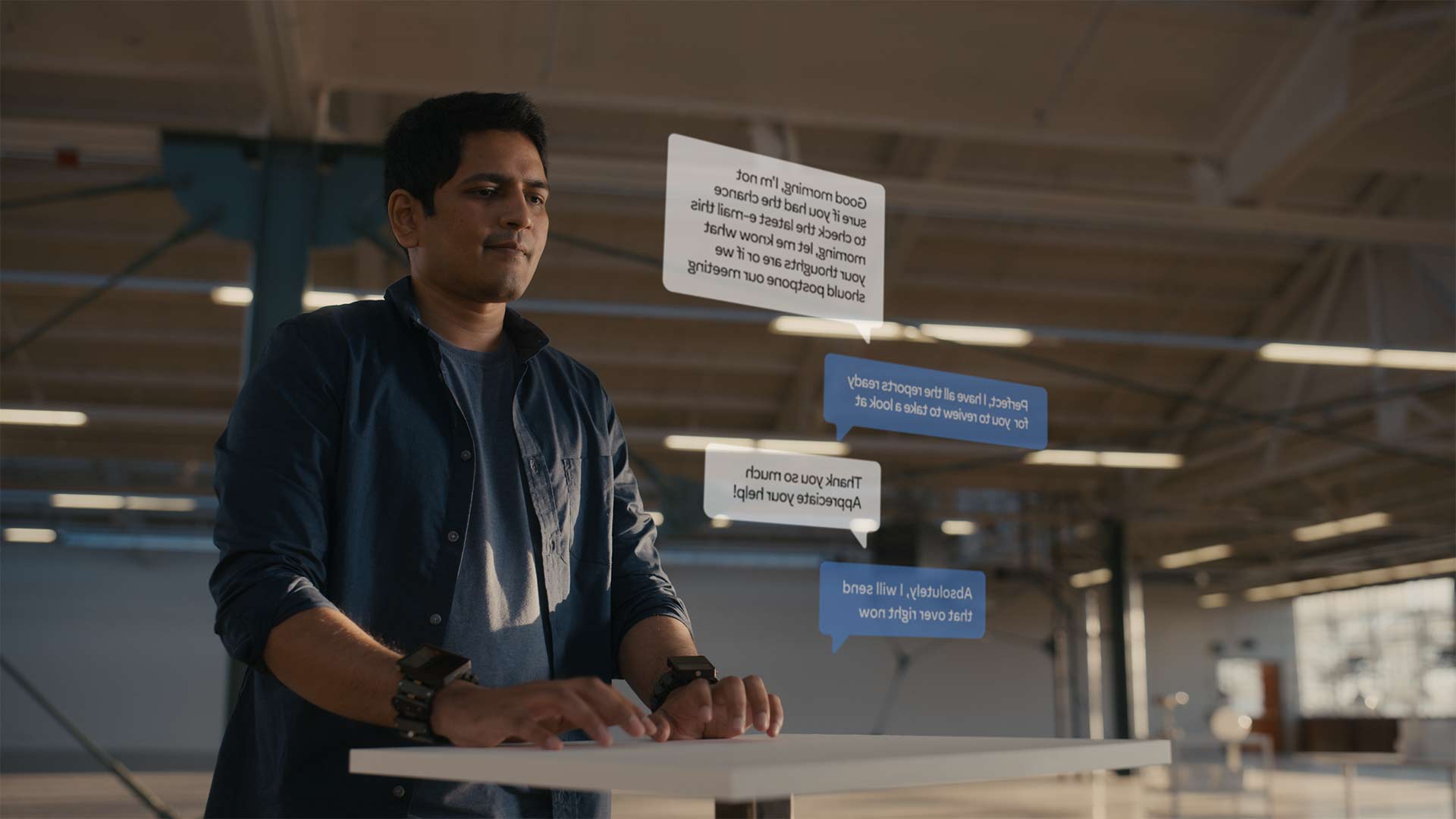

But such a goal won’t be possible without an interface to match. AR glasses like Facebook Aria, will be offering up information at all times in our field of vision, and will be pulling in data from all sorts of sources in order to adapt to a current need.

Pulling in location data, ambient sensor data like temperature and room layout, and even something as simple as time of day, the aim is to have the AR interface understand context to present only what is needed, pre-empting the express intent of a user.

“The underlying AI has some understanding of what you might want to do in the future,” explains FRL Research Science Manager Tanya Jonker.

“Perhaps you head outside for a jog and, based on your past behavior, the system thinks you’re most likely to want to listen to your running playlist. It then presents that option to you on the display: ‘Play running playlist?’ That’s the adaptive interface at work.

“Then you can simply confirm or change that suggestion using a microgesture. The 'intelligent click' [the tap of the AR interface that's presented you information relevant to your current needs without having first summoned it] gives you the ability to take these highly contextual actions in a very low-friction manner because the interface surfaces something that’s relevant based on your personal history and choices, and it allows you to do that with minimal input gestures.”

The beauty of augmented reality is that it can instantly create the perfect device for you. Imagine a digital keyboard, shaped and sized down to the millimeter to fit your hand size and typing patterns, rather than the generic off-the-shelf size that physical manufacturing necessitates.

Physical feel in a digital environment is crucial though, as even the best-sized digital keyboard will be unsatisfying to use without some sense of force beneath a push.

The FRL team showed off two devices looking to answer issues around haptics on the wrist. The first is the “Bellowband,” a wristband containing eight pneumatic bellows which can be controlled to provide pressure and vibration patterns.

The second device is the Tasbi (Tactile and Squeeze Bracelet Interface), which makes use of six “vibrotactile actuators” which squeeze on the wrist. In conjunction, the two can provide feedback that give the sensation of pushing virtual buttons or brushing against differing textures.

At present, neither is ready for the prime time, being cumbersome to wear and requiring external power supplies. But they point towards the sort of sensations that Facebook believes will be critical for an intuitive and believable interaction with digital items.

The ultimate goal then is not just for the world of computing and reality to co-exist, but to coalesce. While the smartphone may have lowered the barrier to entry for computing, AR aims to remove the barriers completely.

Finding a natural user interface and the means to interact will be key to removing the friction between the digital and physical worlds, and these kinds of experiments Facebook is performing are certainly greasing the wheels.

Gerald is Editor-in-Chief of Shortlist.com. Previously he was the Executive Editor for TechRadar, taking care of the site's home cinema, gaming, smart home, entertainment and audio output. He loves gaming, but don't expect him to play with you unless your console is hooked up to a 4K HDR screen and a 7.1 surround system. Before TechRadar, Gerald was Editor of Gizmodo UK. He was also the EIC of iMore.com, and is the author of 'Get Technology: Upgrade Your Future', published by Aurum Press.