Exposed: the great password scandal

How some sites are taking a cavalier attitude to your security

Before reading this article, please pause and take a few minutes to send us your email address and password. We're doing some research to see how many of our readers are friends-of-friends. We'll only log in to your account to look at the address book. Honest.

No? You'd be surprised how many people happily do this via websites each and every day.

Last September, a service called My Name is E launched, promising to solve the 'social network portability' problem – taking the hassle out of adding friends on social networks by aggregating your friend lists on to one site.

You could add a friend on My Name is E, which would then update your contacts across the other sites. Nifty, eh?

People were quick to sign up, eagerly handing over multiple usernames and passwords so My Name is E could do its stuff. Judging by the number of recommendations it was receiving on Twitter, it was clearly an outstanding service.

But there was something odd about these messages. Every recommendation was phrased the same: "I'm now using My Name is E to add friends to my Twitter account! More info on http://hellomynameise.com".

It soon became apparent that My Name is E was logging in to Twitter as each of its users and sending these recommendations as them, but without their permission or knowledge.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"The autotweet was a kind of viral marketing, implemented by one of our developers for teasing our followers on Twitter," says Andreas Creten, My Name is E's lead developer. "Unfortunately, we forgot to disable the feature before we launched."

Angry backlash

The backlash was immediate, with angry complaints on Twitter and customer support forums. "We disabled it as soon as users started complaining," says Creten.

"We were surprised at the response – it was a good lesson. Since we had people's passwords we could take full control of their accounts, but people don't like it when someone else uses their account to do something."

Many of them not only felt angry at My Name is E, but also embarrassed that they were so publicly outed as being careless with their passwords.

A typical message on Get Satisfaction came from Paul Downey, chief web services architect at BT: "Thanks for making me look and feel stupid – it's me that gets to Twitter, not your password phishing bots!"

Says Twitter's API lead, Alex Payne: "We've always advised users to only give their passwords to websites they feel they can trust. Any website runs the risk of compromise, so giving out your credentials is always a gamble. There's little risk in using a desktop Twitter client, but we've cautioned users against handing out their passwords to web-based services that are higher-value targets to attackers."

No big deal?

You may be thinking that this is no big deal. After all, it's only a Twitter password, not your bank details.

But this thinking is flawed. "[Hypothetically] we could easily have logged into people's mail accounts, intranets ..." says Creten, referring to the fact that many people use the same login details across multiple different sites.

Of course, in many cases if a hacker has access to your email account then they have access to all your accounts, because this is where your registration details for different services will have been sent.

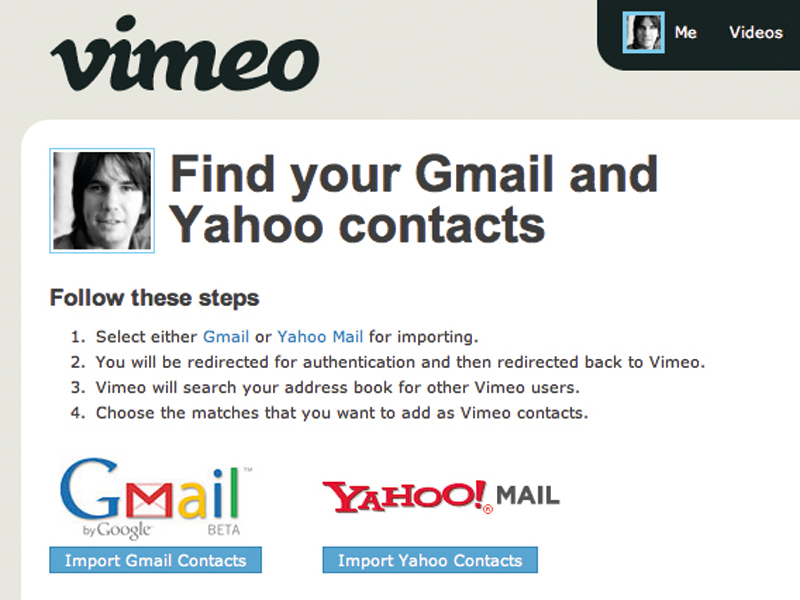

Yet the "give us your email username/password to add your existing friends on this site" routine is becoming more and more common. Twitter does it. So does Get Satisfaction, Linked In, Yelp, Plaxo, Ning, FriendFeed, Orkut, iLike. Hell, giants like MySpace and Facebook do it. They can't all be wrong, surely?

Jeremy Keith, technical director of user experience consultancy Clearleft, is unequivocal: "The message is being sent out that it's okay to hand out passwords from one site on a completely different site. If – or should I say when – this practice becomes commonplace then phishing and identity theft become so much easier: it teaches people how to be phished."

"That should be rephrased 'has taught users how to be phished'," argues Simon Willison, technical architect at Guardian News and Media. "The Facebook thing isn't a smart way of connecting members, it's a horrible precedent."