The smartphone is changing the life of those with hearing disabilities

Digital hearing aid technologies have matured – but what impact will they have on the wider world?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Approximately 360 million people globally have a ‘disabling’ degree of hearing loss, which is just over one in 20 of us.

The World Health Organisation estimates that twice that number – one in 10 people – has some form of hearing impairment, while the UK medical journal Lancet estimates that latter figure to be even higher – 1.3 billion people, nearly one in five. Whichever numbers you go by, it’s a lot of people.

Hearing loss isn’t an inconvenience – it’s a major health condition that can lead to cognitive, physical, social and psychological problems.

“Untreated hearing loss is positively correlated with social isolation, depression, cognitive decline, cardiovascular disease (hypertension, stroke, diabetes) and a host of other factors,” says Dr Dave Fabry, VP of Global Hearing Affairs at Starkey Hearing Technology.

As with so many things in our lives, the smartphone (and other technology) is having a huge impact in this area.

Some smartphone manufacturers are aware of the ability of a hadnset to become an ‘assistive listening device (ALD)’ - for example, Apple has integration with advanced Hearing Aids as standard, including hearing aid management.

It also has a Listen Live function, which allows users to use their iPhone as a microphone feeding direct to their hearing aid.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Hearing Aids Today

Jesal Vishnuram is a Technology Officer at the Action on Hearing Loss charity.

“Current ALDs...aim to improve the signal to noise ratio so people with hearing loss better manage in noisy situations and where hearing aids can be limited,” she says.

This is where the smartphone is perfectly placed to help out: for instance, Starkey Hearing Technology’s Halo2 is an MFI (Made For iOS) device that can stream any audio directly from any iOS device, amplifying and balancing it where necessary.

For tinnitus sufferers, it also includes audio masking to minimize the ringing in their ears. It’s an example of how much modern hearing aids have changed from a few years ago, as Starkey’s Dr Fabry explains.

“[Hearing aids] have evolved from the bulky, beige devices that were worn decades ago. Virtually all hearing aids sold in the U.S. [now] use sophisticated digital technology to process sound with great precision to assist those with hearing loss.

“Few people realize that virtually all custom hearing aids have been manufactured using 3D printing, with over 10 million pairs made to date.”

Yet, those with measurable hearing loss don’t always use hearing aids. Dr Fabry points out that in the US only 30% of those with limited hearing wear them. “Cost, stigma, convenience, and a host of other factors are barriers to use,” he tells us.

Even in countries where hearing aids are free, the usage rates are only between 40-70% - so if hearing aids could be offered to work more cheaply (and easily) with a smartphone then they might become a lot more attractive to the users who need them.

Of course, there are some people who don’t benefit from traditional hearing aids, but need surgical implants in their cochlea (the auditory portion of the inner ear), an idea originally conceived by science fiction writer Hugo Gernsback in 1923.

They bypass much of your sound-receiving system, directly stimulating the inner ear itself using electrodes and an external hearing aid.

“Typically, this means individuals who have a severe-to-profound degree of loss,” says Dr Fabry, “but there are other conditions such as auditory neuropathy or hair cell dyssynchrony that also may benefit from cochlear implants.”

Here, again, the smartphone is capable of helping improve the lives of those with hearing loss: a US project from the Cochlear Implant Lab attempted to improve the speech recognition of the implant for those with the implant by using a smartphone to offer different modes depending on the conditions the user was in.

There are other, more technological solutions available that move beyond the smartphone and into the world of wearables.

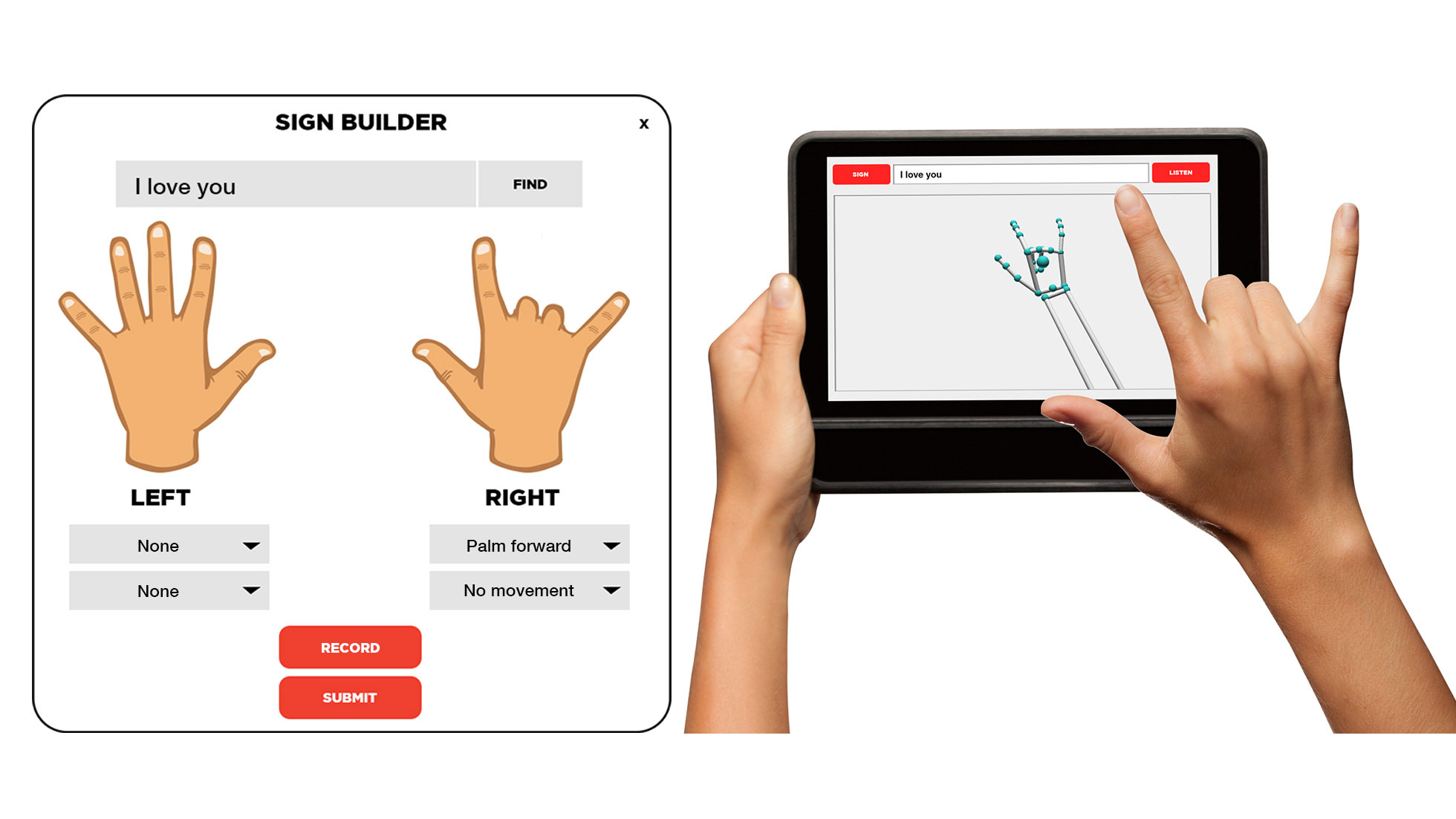

For example, the Motion Savvy Uni is a two-way communication tool for the deaf which uses motion detection to display signs as speech or turn speech to text or signs.

Google Glass might have vanished into the ether, but for deaf users, its integration with 121 Captions means that deaf users can have the world effectively subtitled.

This is particularly helpful to the sections of the deaf community who want to preserve their unique culture, which they see threatened by implants and medical devices.

What's coming?

As we said earlier, hearing aid tech is fairly mature now, having caught up with the mainstream.

Yet there’s much room for growth, as small wearables become specialised and mobile devices get yet more powerful, meaning those wearing ALDs could become even more connected than those without hearing issues.

Action on Hearing Loss’ Vishnuram is optimistic about how advances in hearing technology will assist the disabled community in new ways.

“Wireless and streaming devices are already becoming more available and this is likely to replace traditional technologies such as hearing loops.

“Wearables are starting to compete with traditional devices by incorporating hearing health with other health devices which monitor daily exercise, heart rate and other health conditions as well as apps to act as listening devices through smartphones,” she told TechRadar.

“With improvements in speed of processing sounds, mainstream technologies may be suitable to compete with traditional [hearing aids] for milder hearing losses in the near future and possibly more complex hearing losses in the long term.”

Starkey’s Dr Fabry strongly agrees. “Certainly, there are many exciting developments in [this] field, including the development of ‘hearable’ technology that measures biometric information (HR, body temperature, glucose levels, pulse oximetry, etc.) in addition to amplifying sound.

“The ear is tremendous real-estate for measuring biometric data, and we believe strongly that ‘the ear is the new wrist’ for extending the benefits of ‘wearable’ technology to the ear.”

And there’s always room for even weirder elements. Lovers of TED talks might remember David Eagleman’s impressive VEST.

It’s a conceptual piece of clothing which detects sound waves through a microphone and replicates them in a series of vibration motors all around the human body.

Neural plasticity means the brain would be capable of developing these impulses into new senses, effectively augmenting one’s hearing, which would be excellent for disabled communities.

The wider world of hearables

Meanwhile, Microsoft was rumored to be entering the hearables space with the Cortana Clip.

This functions as a smart voice-operated personal assistant, much like Siri on iOS, and integrates with Windows Phone, iOS and Android, as well as their associated home control systems, like Nest, and would be created with a more jewellery-like design in mind.

That said, the Clip was rumored back in the latter end of 2015, and nothing has officially appeared from the Redmond brand, so it might be that the project was canned.

Other hearables are appearing on the market though. Doppler Labs’ Here earbuds take much of the tech of headphones and hearing aids, and give you control over your audio environment - blocking out all sound except those elements you choose to listen to.

The Motorola Hint and Bragi Dash are similar to this, as are the Samsung Gear IconX and Sony Xperia Ear.

Waverly Labs’ Pilot, by contrast, is an automated translation device, like Douglas Adam’s Babelfish, translating all the nearby speech you hear into whatever language you want - great both if you don't speak a language, or want to learn a new one at home.

And there’s more that takes hearables away from the ear, like Eagleman’s vest.

The Sonna is a prototype device that lets the wearer experience selective data from the environment as a three-dimensional soundscape. It was developed by a team from the Royal College of Art and Imperial College. Allison Rowe was a designer on the project.

“It’s a type of augmented audio reality,” says Rowe. “Every second there are countless streams of information, and our only access is to a small portion of this through screens, dashboards, signs, and other visual representations.

“We want to allow you to tap into them intuitively. So we convert this data into sound - a form you can process in parallel with your other mental tasks - and provide it via a bone-conduction headset, which does not occlude your usual hearing.”

Users choose a data source - the city bus network, say, or your family’s geolocations - and they can constantly ‘hear’ these key locations as a background seventh sense. The bone conduction means it’s suitable for the hearing disabled as well as being relevant for the visually impaired.

“Rather than relying on voice-based turn-by-turn directions, and feeling like she is at the mercy of her device, the wearer would instead have an intuitive sense of where and when to turn as well as the location of the final destination,” adds Rowe.

Sadly, Sonna is only a prototype currently and isn’t due to have a commercial release - with the team still hoping to partner up with other firms to bring it to market.

While there are laudable efforts to rid the world of diseases like deafness - include gene therapy - Rowe is confident that this is only the start and that advances in artificial intelligence will lead to smartphones and other device intelligent enough to fully communicate their surroundings to the user.

“In a simple example, a hearing person on a loud and crowded train presents the same issues as a hearing impaired user - voice control and speech-based responses are not ideal,” she says.

“More nuanced than this will be personalizations that take into account far more than simple “preferences” - the ability to tune into and out of different voices so that I can hear the person I’m conversing with but not be distracted by the couple at the neighboring table.

"We’re excited about new ways in which people interact and engage with each other and the world around them, and technology that pushes us closer rather than farther apart.”