How 3D video chat and sound is shaping up

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When talking about the prospect of 3D telephony, it's easy to get distracted by the newest 3D phones like the HTC Evo 3D and the LG Optimus 3D. However, while impressive, these devices don't let you make calls in 3D. What are the odds of

video chat happening?

When (if ever) will we be able to recreate that famous scene from Star Wars in which R2-D2 plays Princess Leia's holographic voicemail message? Disappointingly, we're a long way from being able to beam 3D video from pico projectors in our phones or laptops, but the technology exists.

Scientists at the University of Arizona in Tucson have created a system to capture a 3D image and transmit it (in near real time) anywhere in the world. According to Nature journal's website, the team's system "captures 3D information by filming an object from multiple angles, using 16 cameras that each take an image of the object every second. The 16 views are processed into holographic pixel data by a computer."

The resulting three-dimensional holograms are small and slow, but you could have one in your home by 2020. Can't wait that long? Video conferencing specialist TrueConf has developed a 3D version of its popular business software, which can broadcast a 3D video stream thanks to twin cameras mounted on PC monitors. Conference participants need to don Nvidia 3D shutter glasses to get the full effect. TrueConf 3D will be available late 2011 with a price tag of $5,000 (around £3,000).

3D sound

Think that surround sound is 3D sound? Think again. While traditional 5.1 and 7.1 speaker setups can produce a rich soundstage, the audio is mixed to conform to specific channels and speaker placements. The closest you'll get is sitting in the sweet spot of an 11.1 system, which consists of five front speakers (two of them at height), four side speakers, two rear speakers and a subwoofer. It's not ideal for most homes.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

What we really need is a virtual solution, and Edgar Choueiri, Professor of Physics at Princeton University, is close to giving us one. Disappointed with the realism of traditional surround sound systems, Choueiri developed an audio filter that works with standard stereo speakers.

"With 3D audio, I can get a fly to go around your head," he told the BBC's Today programme. "Or if you want to really scare somebody, you can put a sound inside their head."

Professor Choueiri's work has the potential to revolutionise home audio, and he has recently formed a partnership with Cambridge Mechatronix (CML) to develop the Dynasonix 3D sound system.

According to CML, the technology works by focusing a pair of sound beams on each of several listeners' ears, tracking their positions in realtime with a camera and delivering cross-talk cancelled 3D audio to each listener. As a result, each listener gets their own individual sound field.

"This gives you a comparable sound experience to headphones, but without the headphones," says CML.

When 3D goes wrong…

Autostereograms

What do you do when you want 3D without glasses, but you can't simply project a 3D image? If you're sensible, you wait 20 years for technology to catch up with your plans. If not, you ask people to squint until patterns of dots coalesce into shapes at around 30 frames per second.

This is how 3D was simulated in Magic Carpet, a game from 1994, and if you could play it like that, you deserved a prize. That prize: a lifetime supply of paracetamol for the headaches you'd soon be all too familiar with. Most players soon gave up and returned to the regular 2D graphics, and not without cause.

Virtual reality

The concept was brilliant - a helmet that puts screens up to your eyes, immersing you in a full 3D world. The downsides? Heavy equipment, nausea from having no actual sensation of movement, and very primitive computers handling the grunt work.

The most common VR machines, found in arcades in the early '90s, were powered by an Amiga 3000, and were too limited to be anything but a novelty. Several attempts were made to reignite the concept, but with the intrusive nature of even the slimmest headsets and little to no actual software support, they never caught on.

Virtual Boy

The first major 3D games console to hit the market was also the last until this year, when Nintendo launched the 3DS. Being too big and heavy to be portable, too loud to be ignored, and with practically no games support would have been a killer for any system, but the Virtual Boy went one step further by only using a single colour in its graphics, and that colour was red.

Rarely has a system been so painful to use for any length of time, or so badly conceived. It lasted a single year on the shelves, but retains its reputation as one of the worst consoles ever created.

VRML

The problem with the Virtual Reality Markup Language wasn't simply that it was slow and unimpressive, but that its supporters misjudged what the internet would be. VRML was the language of cyberspace, where we'd walk around a web of 3D mansions and supermarkets, recreating interactions in a virtual context.

Instead, the world realised that clicking on hypertext was easier, and cheaper. After attempting to convince everyone otherwise, the software industry saw sense and surrendered.

Ecstatica

Most games are built around triangular polygons because they're what 3D accelerator cards were originally built to use. There have been other technologies over the years, including voxels (pixels with depth, originally used to create landscapes in games like Commanche, and which can still be seen in games today) and the hilarity that was ellipsoid-based modelling.

This began and largely ended with Ecstatica and its sequel; two horror games full of torture and Satanic plotting (rated 18) rendered hilarious by being, quite literally, a load of balls.

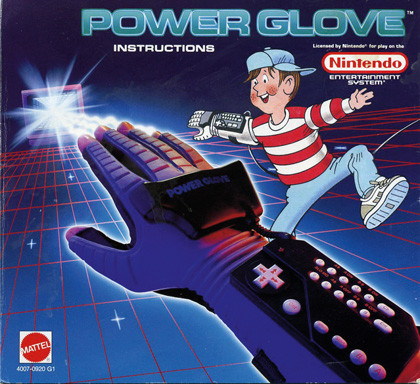

3D controllers

There have been a few brave attempts to create 3D alternatives to the keyboard and mouse. Mostly, these have failed for two reasons: it can be very tiring to have your hands constantly hovering or gripping a controller, and even if the technology is up to scratch (unlike the Power Glove, above, which used ultrasonic sound to detect its position), there's no haptic element to help you sense items in the space.

Add in a tendency to be imprecise yet unforgiving, and it's no surprise that the keyboard and mouse are still the tools of choice.