Google Glass is back, but for these people the AR wearable never went away

The failed consumer wearable has been reborn for business

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Google Glass arrived three years ago. Like most, TechRadar's Matt Swider found it an interesting piece of technology, but one that did little and cost a lot. It was a neat proof of concept that you couldn’t imagine many people buying, and few were surprised when Google stopped production in 2015.

Except it didn’t, really.

Last month Google announced its intention to sell Glass Enterprise Edition to businesses across the world, and it's now on sale. However, companies are already using an enterprise/business version of Google Glass, out of the public eye, and have been working with Google on developing for Glass since it first appeared.

There’s hidden magic going on, and we’ve talked to some of the people and companies innovating with Glass to see what we’ve been missing, from building jet engines to helping out with invasive surgeries.

Who’s using Google Glass?

I have my own memories of Google Glass, having written about the headset when it first arrived. At one point I ended up wearing it while wandering around a small town in the east of England called Bungay. It may have been the first, and last, time Bungay saw Google Glass.

Taking terrible photos, receiving even worse navigation instructions and looking for hate in the eyes of small town passers-by made up the bulk of the Google Glass experience. It’s no wonder the wearable has enjoyed more success as a sort of heads-up display for businesses, who don’t need Glass to be fun or packed with functions.

“It’s a common question actually: what do smart glasses do fresh out of the box? The answer is not much,” says Brian Ballard, CEO of Upskill, a company that makes enterprise software for augmented reality devices. “They have a pretty stripped down OS designed for networking and loading an application.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Upskill is the company behind Skylight, a platform that fills the somewhat empty circuit board sandwich that is Glass. The scale of its operation gives you some idea of how much Google Glass action we’ve missed. “We’ve got 35 Fortune 500 customers, and a handful more across the global 2000. I’m not sure if we’re in Africa right now but we’re in every other continent,” says Ballard.

Some of Upskill's biggest clients are aviation giants like Boeing and GE Aviation, whose engineers and mechanics use Glass in their work maintaining jet engines.

“Say I walk up to my workstation, I look at a code that identifies I’m building a sub-assembly for a jet engine. Our software reaches out, pulls down all the data, translates it into work instructions and makes that visible to the person,” Ballard explains. “As they’re going through the job they don’t constantly have to have someone to say ’go to the next step’, It’s just part of their workflow.”

Skylight breaks the job down into a to-do list the mechanic can refer to just by looking up and right, rather than heading to a manual on a work bench.

The more you hear about how Google Glass is used, the more it sounds like a form of human automation, turning us into robots before the actual AI robots turn up; Ballard calls it “lowering the cognitive load”. However, any Skynet overtones evaporate when you think about Glass being used in a retailer's warehouse, which is another use for the headset, rather than a jet engine facility.

“We do a lot in material handling, pick and pack in a warehouse; it’s what everyone imagines amazon.com looks like,” says Ballard. “There are endless rows of shelves, and I’ve got a barcode gun that tells me to go to row 45, shelf 13, bin 4. And the average person’s like ’I don’t know where on earth that is’. Smart glasses could tell you really quickly where you’re going – you remove all the confusion and wasted time thinking is it left or right?”

Ballard also confirms the glasses Upskill is working with are the enterprise sets we’ve just heard about, rather than the classic consumer version. “The glasses, a consumer would recognize. But there are tweaks to it. It’s foldable, and there’s tool-less removal of the glasses part, so if you want to switch different frames it’s easy,” he says.

Google Glass vs jet engines

After getting a primer from Ballard and Upskill, we went to the source and talked to Ted Robertson, Manager of Maintainability & Human Factors Engineering at jet engine manufacturer GE Aviation, about how the company uses Glass.

While Upskill has worked with Google since Glass arrived, Roberton and his team only started in early 2016, when to most Glass was fossilizing as a tech memory. At that time GE held a competition across its many arms, including medical, automative and the energy-related sides of General Electric, to find a good use for Glass. GE is a major investor in Upskill, and has a vested interested in making Glass useful.

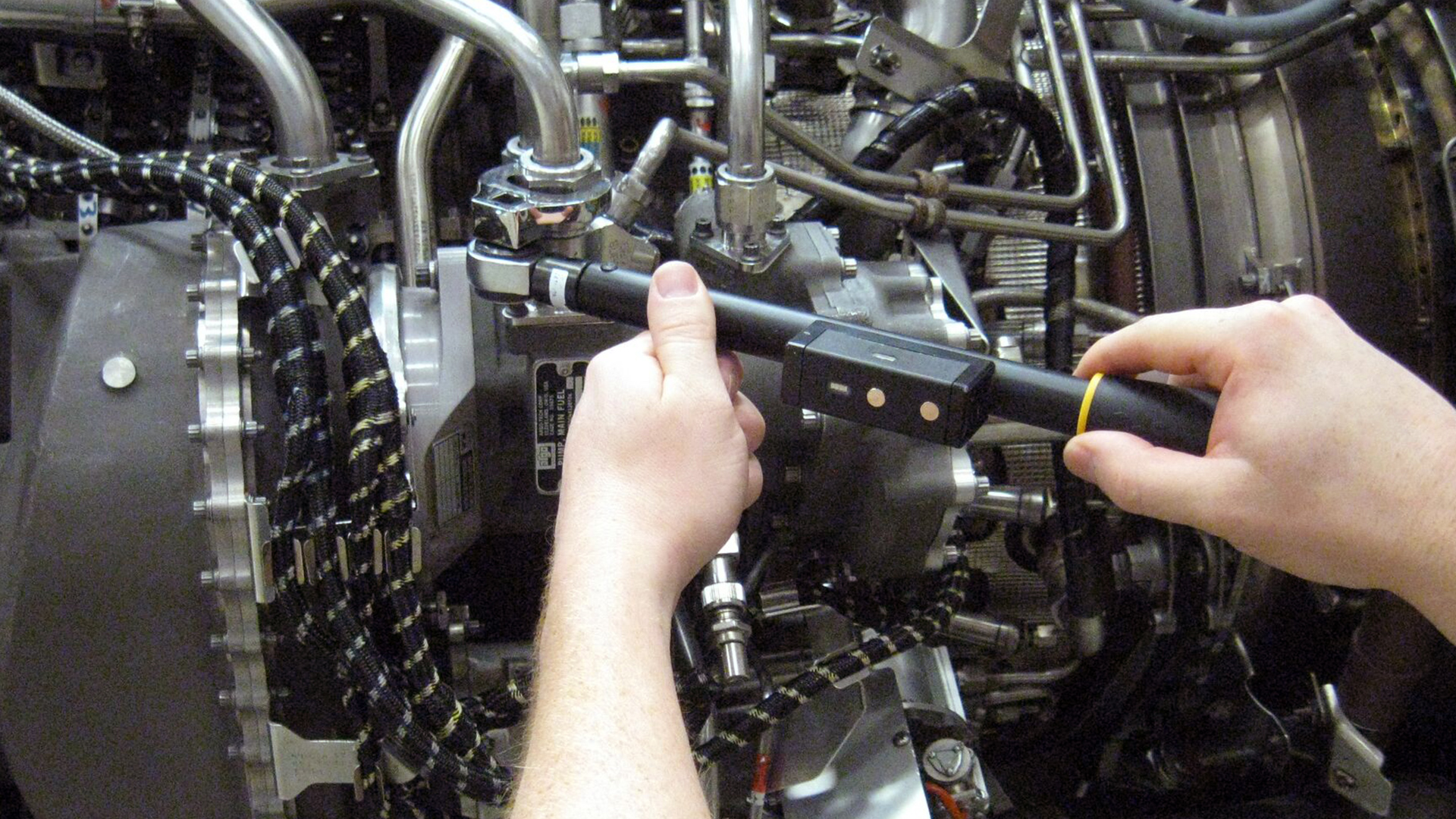

GE Aviation’s idea was as nerdy as you’d hope from a bunch of jet engine engineers. “The novel part of what we wanted to do was to take a smart torque wrench… and integrate the wrench with Google Glass and the Skylight software, so there is a real-time display of the torque [the engineers] were applying,” says Roberton.

A torque wrench is what mechanics use to tighten bolts in a jet engine assembly. And, as you might guess, a smart wrench has Wi-Fi, enabling it to wirelessly relay the force applied.

As they’re working on a giant engine assembly, a mechanic can just look up and right at the Glass display to see whether they’re about to shear off the thread, which can cause a ’leaking oil line’ according to Roberton.

It’s not quite the cool side of AR headsets most of us thought about on first seeing Google Glass, but it’s pretty important. “Any time you’re flying on a commercial aircraft or regional jet there’s a good chance you’re being propelled by a GE engine,” says Roberton.

So far, GE Aviation has performed a 15-engineer trial of Google Glass with Skylight, and, adds Roberton “we think we can employ this essentially in any place we’re doing assembly”. It’s not hard to imagine an army of engineers all wearing Glass. But as Roberton goes on to explain, we’re not going to see a sudden company-wide roll-out in somewhere like GE. It has over 300,000 employees in total. It’s no agile startup.

Cutting you open with Google Glass

It takes a smaller operation to move more quickly with something like Glass, and for that take we talked to Paul Szotek, a surgeon based in the US state of Indiana, and one of the pioneers of using Google Glass as a medical tool.

Szotek's experiments with the headset go back to its earliest days. At the time he worked as an EMS (emergency medial services) doctor at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, home of Indy 500 motor racing. He experimented with the headset, using it to stream video from each corner of the track, communicating between the on-site emergency medical crew and the local hospital.

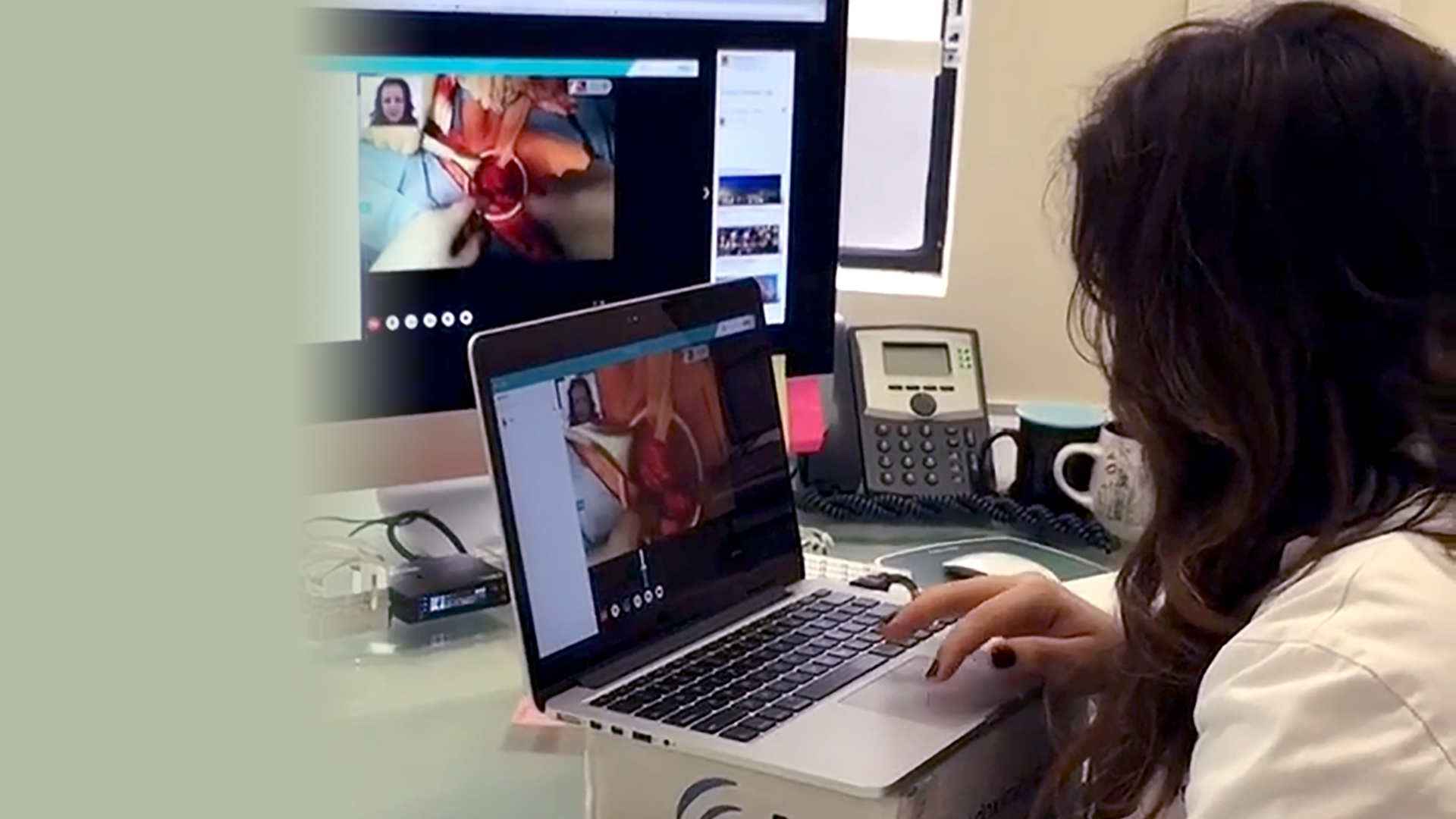

Szotek now runs a hernia repair center, and works with a company called AMA, which makes Google Glass platform Xperteye. This enables a Glass headset to broadcast video of what the surgeon sees, and allows them to consult with other medical staff or surgeons to receive ’telestrations’, which in this case might be annotated patient scans, as they work.

“When I’m travelling I’ll have my nurses wear the Xperteye solution, so if I have a patient come by with a wound problem I can visually guide them through how to change the wound VAC,” says Szotek. A wound VAC is a rather involved form of dressing often used in cases of burns, where a negative pressure vacuum is used to draw out fluid to prevent infection. Just don’t think about it too much if you’re squeamish.

Szotek has used it for his own surgical work too. “I had been referred a patient who had a recurring abdominal wall tumor. I loaded up the MRI with landmarks into the Google Glass and put in on a loop. We were able to look at it while I was in the field, continually refer to it, without actually leaving the table,” says Szotek. “That was one of the first augmented reality tests in the operating room, to guide better patient care. That was in the winter of 2015.”

While the current version of Google Glass has a relatively low-resolution sub-HD display, you can already picture a medical procedural TV show reproducing this like the heads-up display of a fighter pilot. Which is actually not too far off the reality.

Szotek sees one of the main benefits of using Glass as something simpler, though. “We train surgeons all the time from the opposite side of the table,” he says. “You’re learning in a mirror image from what you’re actually doing. That’s very difficult.”

“They can’t actually coordinate verbal cues with visual cues,” he adds, and by giving us the surgeon’s-eye view, Glass fixes this problem. Szotek compares it to teaching your child how to tie their shoes: it’s much easier if they’re on your lap rather than in front of you.

The future

Talking to these ‘hidden’ Glass users, there’s a definite sense this is just the beginning. But unlike with consumer gear, enterprise users are waiting for the tech to progress, rather than being dragged along by the sheer pace of it.

One thing Szotek is after, for example, is to be able to “take the laparoscopic feed and combine it” with the standard information feed. That’s the video from a tool put inside a patient without cutting them wide open. But this isn’t easy.

Szotek worked on this project with a former partner, but found that lab-condition tests rarely translated into great real-world results. “I’ve dealt with several shady startup tech companies, and every time you go to use it in the OR, it doesn’t work,” he says. ”You’re like: you don’t get it, it can’t not work, it needs to work 100 percent of the time. This is people’s lives. The reality of it is the technical demand is significant.”

His vision for Glass is far in excess of what we have right now. “You need to be able to integrate lab data, vitals, somebody telestrating for you, radiology,” he says. ”Those are all the key things we need, along with what’s coming in the future: image guided surgery, which is taking a big look into the future because we’re not there with the tech.“

But, as Szotek says, it needs to work 100%, of the time.

GE itself did some Google Glass future-gazing back in 2013, with a mock-up video showing the headset recognising engine parts and bringing up schematics. Four years on, we’re still not there yet.

“If you looked at an engine it would not be able to display pinpoints of all the different parts, where the component are,” says GE Aviation’s Roberton. “That would take a lot more sensors, a lot more computing power. But it would be nice if we could get there one day. I’m sure we will.”

Andrew is a freelance journalist and has been writing and editing for some of the UK's top tech and lifestyle publications including TrustedReviews, Stuff, T3, TechRadar, Lifehacker and others.