Going online in countries where internet censorship is common is rather like visiting a parallel universe run by the world's strictest, most bigoted parents. Entire sites disappear without warning.

YouTube is frequently blocked for hosting content that some regimes don't want their citizens to see, and online translation services, blogging platforms and even VoIP utilities like Skype often fall foul of censors.

Local sites are also very selective about what they publish or link to. Bloggers rot in jails for daring to criticise politicians or religious leaders, while millions of people are denied internet access altogether, limited to an incredibly narrow selection of officially approved pages or subjected to constant and chilling levels of surveillance.

Restrictions on freedom in some parts of the world put the UK's situation into context. When we worry about plans to monitor our online activities or make certain kinds of content illegal, we're complaining of a headache to someone who's just been decapitated.

In these countries, keyword filtering and ISP blacklists prevent you from accessing any sites that the government doesn't think you should see. Depending on where you are, the list can be a very long one; among sites blacklisted are those dealing with women's rights and general human rights, different political or religious points of view, Western pop music, foreign news sources, gambling, mentions of alcohol or drug use, stories that portray the ruling regime as less than perfect and even information sites such as Wikipedia.

China is one of the world's most infamous internet censors. In addition to the Great Firewall of China – a large network of filters that blocks content and scans messages for 'subversive' keywords – Chinese internet users have become familiar with JingJing and Chacha, two cartoon police officers who pop up on their screens to remind them of the rules.

INTERNET POLICE: Meet JingJing and Chacha, the friendly faces of Chinese state censorship who pop up regularly to remind people of the rules

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Sites that raise sensitive subjects are either blocked, criticised in official media, fined, ordered to dismiss webmasters or shut down. China is far from the only country that censors content. Tunisia blocks sites known to be critical of its government.

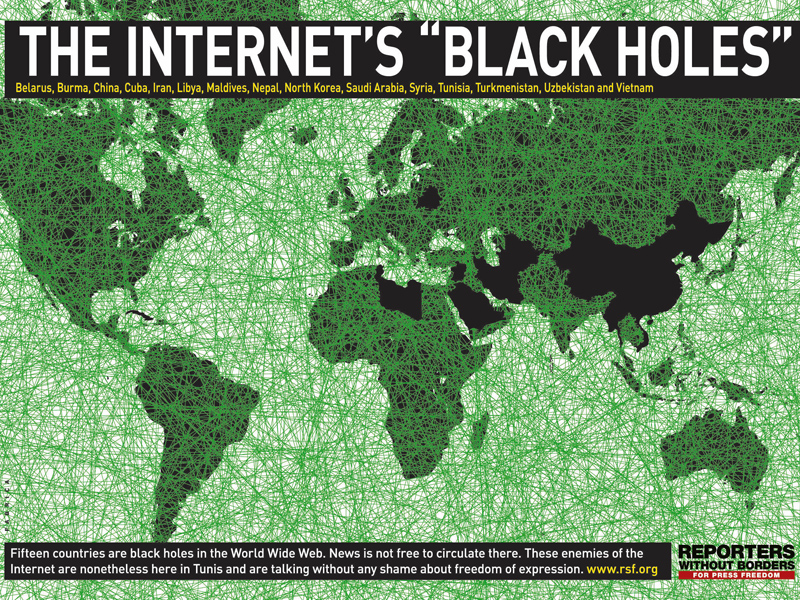

Saudi Arabia filters content to the extent that some 400,000 sites are blocked due to 'immoral' content; campaigning organisation Reporters Sans Frontieres (www.rsf.org) notes that the censorship is so strict that it's effectively impossible to search for basic health information, such as advice on breast cancer.

Iranian website owners have to register with the government before publishing online, while 'immoral' sites such as Flickr and YouTube are banned, and ISPs must ensure that prohibited content is not available via their servers.

Access denied

Governments don't just limit what people can see online – they also limit how they get on to the internet in the first place. Iran banned high-speed connections in 2006, partly to protect its creaky network infrastructure, but also to prevent Western cultural products – music, movies and so on – from becoming easily accessible.

In Cuba, citizens have to use government-controlled access points that monitor the keywords they search for and the sites that they visit. In Vietnam, reports claim that 'cyberpolice' monitor people's activities in internet cafes.

In 2007, the Burmese government responded to antigovernment protests by shutting down internet access for the entire country. And in South Korea, citizens have to provide their official ID numbers in order to gain access to many websites.

Sometimes the gates to the web are closed by accident. In 2006, Zimbabwe's internet connectivity suffered a major setback when the state telecoms company didn't bother paying its bills. Satellite communications firm Intelsat promptly cut off 90 per cent of the country's internet access.

It's doubtful that Robert Mugabe's government was greatly worried by this; even where people can get connections, ISPs must help the government to locate the authors of any messages considered 'harmful' and 'take the necessary measures' to prevent illegal material from being published. Even when countries don't use blanket censorship or beat up bloggers, the climate can be chilling.

In Belarus, legislation passed in 2007 forces the owners of cybercafes and computer clubs to report anybody visiting 'sensitive' websites to the police, while sites critical of the government have an unfortunate tendency to succumb to distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks.

Tunisian cybercafe owners are responsible for the activities of their users, which means users are often asked for ID before logging on and then warned away from 'subversive' sites. The penalties for breaking the rules can be severe.

In Egypt, Hala Al-Masry's Cops Without Boundaries blog attracted the attention of the authorities. She was harassed by government officials, her father was mysteriously beaten up, and she and her husband were arrested and forced to shut down the blog.

In Burma, Maung Thura is serving a 59-year jail sentence for publishing footage of the aftermath of the devastating 2008 cyclone. In Iran, Omidreza Mirsayafi was jailed for insulting the country's religious leaders; he died in prison in mysterious circumstances.

In Syria, Waed al-Mhana faces jail for criticising the government's decision to demolish a historical market, and China has jailed 48 bloggers for 'inciting subversion'.

Current page: Blocking sites and controlling internet access

Next Page Who is colluding with the censors?