It couldn't happen here

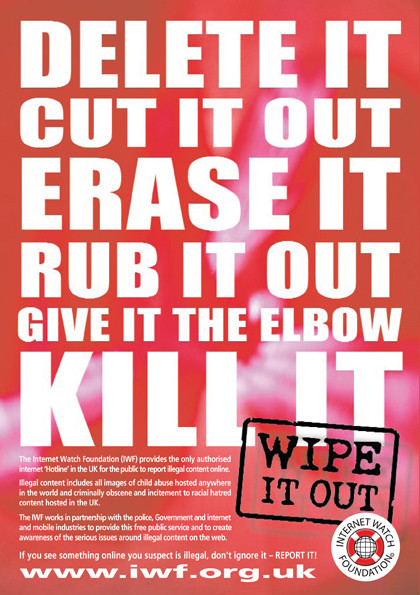

Could censorship happen here? It already does. Around 95 per cent of residential internet connections pass through filters that compare requested URLs with the Internet Watch Foundation's blacklist, a secret list of sites that host child pornography. However, despite concerns about the IWF itself, there's no suggestion or evidence that the IWF list deliberately blocks anything other than illegal porn.

It's not compulsory, either: ISPs don't have to use the blacklist if they don't want to. That doesn't mean that things won't change in the future, though. In Australia, the government proposed – and then shelved – new legislation which would have introduced mandatory filtering of all online content to prevent X-rated material (that's content that would be classified R18+ or X18+ in the UK) from being seen by minors.

Any such content that wasn't protected by an age verification system would be deleted if hosted on Australian servers, or the site blocked if the files were hosted somewhere outside of the country. As the Australian proposal demonstrates, protecting children from smut can easily lead to heavy-handed censorship. Could the UK implement similar filtering? The Scots might.

England, Wales and Northern Ireland recently criminalised downloading of 'extreme' – that is, violent – pornography, but the Scottish Government intends to go further. Its new Criminal Justice Bill doesn't just criminalise actual violence; it would also make it illegal to possess images that "realistically depict life-threatening acts and violence that would appear likely to cause severe injury [or] non-consensual penetrative sexual activity."

The difference between the Scots legislation and the rest of the UK raises the faintly absurd prospect of Porn Police checking Englishmen's laptops at airports and train stations. It also shows the problem of instigating any kind of censorship, no matter how well-meaning: if the IWF blacklist were forced to follow the Scot's criterion, it would arguably have to block clips from Hollywood movies such as Hostel 2, which realistically depicts life-threatening violence in a sexual content, or Irreversible, which features a protracted rape scene.

IWF: The IWF blocklist filters illegal porn – but ISPs don't have to subscribe to it if they don't want to

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Keep calm and carry on

Over the years, pressure groups have demanded that UK ISPs filter pro-anorexia websites and other potentially dangerous content, and copyright owners want filesharing sites such as The Pirate Bay blocked.

However, even when blocking particular kinds of content is unlikely to cause public outcry, the British government shies away from outright censorship. For example, in April it emerged that the Home Office was taking steps against websites that promoted anti-Western, extremist views. It wasn't blocking them, though: rather, it was teaching search engine optimisation to the webmasters of pro-Western, moderate websites so that their sites would become more visible.

It may sound bizarre, but the recent Damian McBride email scandal typifies the government's attitude to the internet: faced with strong criticism from right-wing blogs, government insiders tried to fight back by circulating smears about their opponents. The plan was many things – including reprehensible, morally bankrupt and doomed to failure – but it wasn't censorship.

In some countries, the government would simply have rounded up the most critical bloggers and made them disappear. In the UK we're lucky enough to live in a country where our internet access is largely unimpeded, and where we have the freedom to launch online petitions, copy all our emails to Alan Johnson and write angry blog posts about real or perceived threats to our privacy without fearing either persecution or a prison sentence.

That doesn't mean that we shouldn't be vigilant, of course – never underestimate the power of a newspaper 'ban this sick filth' campaign or a 'terrorists are using Twitter' scare story – but perhaps we should be counting our blessings at the same time.