How to break the internet

Just as our dependence on the web is growing, so are the threats

What is the internet? This might sound like a stupid question, but perhaps the best way of describing it isn’t – as one US congressman once put it – as a series of tubes – but rather as a tool of liberation. As internet connectivity has grown it has empowered billions of people. We can now carry around the collective brain of humanity in our palms, and this is completely normal.

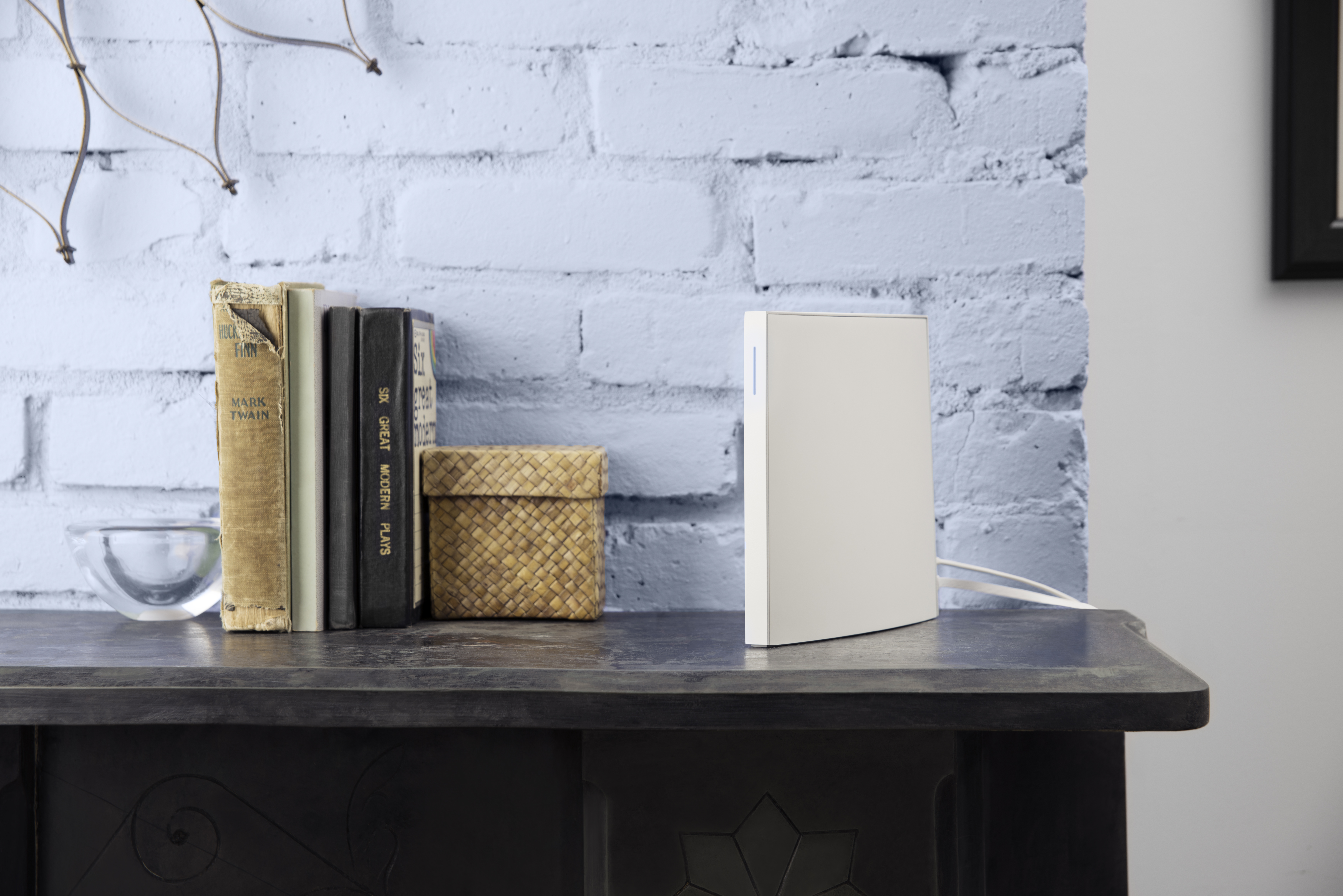

And this is also why it’s absolutely infuriating when the lights on your BT Home Hub turn from a reassuring blue to an angry orange. The vast majority of the time, of course, they’ll switch back a few moments later, so you only have to spend a few brief moments disconnected from the rest of the world.

But what if your connection goes down for longer? And what if it wasn’t just your connection but those of thousands, millions or even billions of people? Could this even happen? It’s almost too scary to contemplate but... is it possible to break the internet?

TechRadar spoke to leading online security experts to learn more about some of the internet’s biggest vulnerabilities.

The Dyn attack

The internet, of course, has no single ‘off’ switch; it’s a patchwork of networks, servers and nodes, all of which can operate independently of each other – but that doesn’t mean our internet infrastructure is indestructible. And – leaving aside some catastrophic solar flare that wipes out all global electronics – terrestrial cyber threats have the potential to break the internet for millions of people.

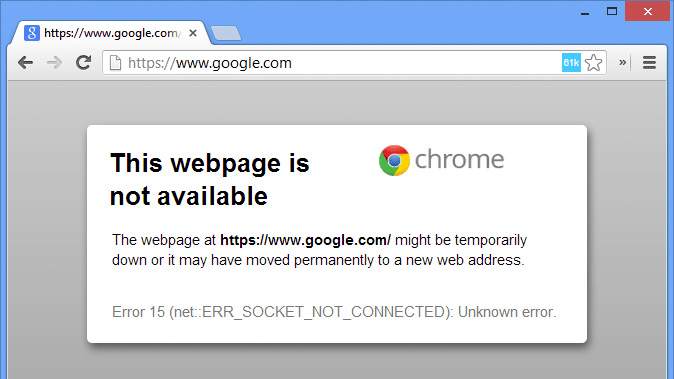

In October of this year, the hacking groups Anonymous and New World Hackers took responsibility for taking down DNS (domain name system) provider Dyn, which in turn knocked out dozens of the largest web services for millions of users in North America and Europe. Amazon, the BBC, Netflix, Twitter, Spotify, Playstation Network and Xbox Live were among the highest-profile casualties. Even the British government’s website, GOV.UK, was briefly made unavailable by the attack.

“DNS servers are today’s biggest targets and vectors for hackers,” explains Hervé Dhélin from EfficientIP, a leading provider of support services to internet service providers. “This is because when the DNS server is unavailable nothing can work – without the DNS there is no connection, therefore no business – so hackers achieve their ultimate goal of causing downtime for a company.“

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

“DNS servers are today’s biggest targets and vectors for hackers.”

Hervé Dhélin, EfficientIP

Attacking DNS servers then, appears to be the most efficient way of doing damage. Bogdan Botezatu, Senior E-Threat Analyst at Bitdefender, described how Dyn’s DNS servers provided this single point of weakness for many users – and how the attack was carried out.

“Since it is responsible for the name to IP resolution of all domain names, overloading the DNS infrastructure with queries will render it inaccessible to other users who need to interrogate what IP a domain name points to,” he said.

Essentially, the pipes to the DNS servers were so blocked up, normal requests couldn’t get through.

So how was the attack carried out? If hackers want to bombard DNS servers with requests, they need to come from somewhere. The Dyn attack was a distributed denial of service attack, meaning the requests originated from hundreds of thousands of computers, controlled using the Mirai botnet malware – essentially a virus that enables hackers to take control of your computer and direct it to do stuff. In this case, they were directed to attack Dyn.

“There are millions of IoT devices that are not being monitored.”

Matt Little, PKWARE

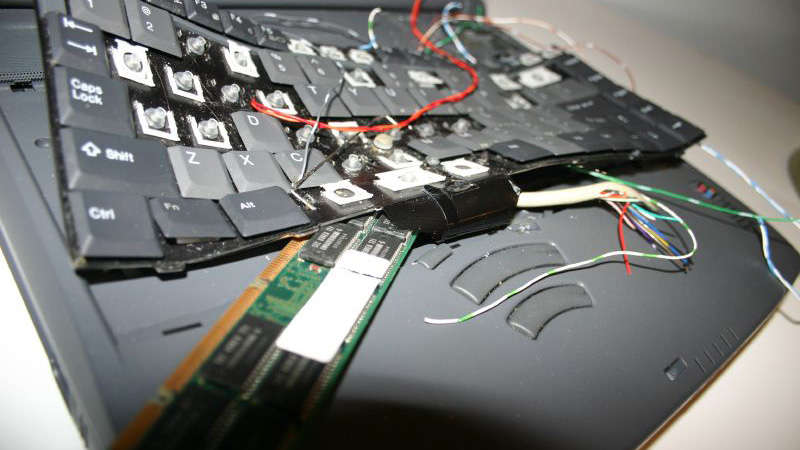

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the Dyn attack, though, is the nature of the computers that the hackers managed to load the malware on to: the overwhelming majority of affected devices were not laptop or desktop computers, but internet of things (IoT) devices, such as connected security cameras and thermostats.

And it appears that the Dyn attack may have been a mere foretaste of what is likely to become a big security headache as IoT devices become more ubiquitous.

“IoT devices have been built with very little security – and even worse, very poor security in most cases”, warns Matt Little, from encryption firm PKWARE.

“There are millions of IoT devices that are not being monitored.”

Sean Ginevan, from enterprise security firm MobileIron, agrees that the way these devices have been manufactured is the problem. “Manufacturers took security shortcuts, and did not build in mechanisms to secure the devices and patch them in the field without doing a massive device recall,” he explains.

And this is why IoT botnets could be a big problem in the future. The Dyn attack is estimated to have used anywhere between a relatively modest 100,000 and two million devices (depending on who you believe), and yet they were able to gunk up the internet’s tubes with 1.2 terabits per second of data – and that number will become a drop in the ocean as more devices come online. It’s conceivable that, right now, there are millions of unsecure connected devices just waiting to be used – and with the manufacturers who created them unable to remotely patch or recall them.

“There exists the potential for far bigger botnets, if you look at the poor security track record these devices have had in the past,” a spokesperson for Malwarebytes Labs told us. He added that a larger attack could combine multiple vector techniques to maximise the damage.

“There exists the potential for far bigger botnets."

Malwarebytes Labs

For example, a ‘SYN Flood’ could tie up server resources by sending malformed connection requests. A very simple way of explaining this might be to imagine someone holding out their hand for you to shake, only for you to leave them hanging, and then that person putting out the other hand and you doing the same thing – meaning they have no hands left to shake anyone else’s hands.

There are numerous other types of attack, all of which variously mess with the protocols computers use to connect to each other, such as UDP fragmentation, or DNS Reflection. Crucially, though, Malwarebytes reckons the most damage could be done if multiple DNS services were attacked simultaneously – if a large enough botnet were set against not just Dyn but other providers too, like Akamai, Rackspace, ClouDNS, Namecheap and CloudFlare. This is when we’d all definitely start to notice something was going wrong.

Main image: CC image courtesy Sarah Baker

- Before you do break the internet, download the best free PC software of 2016