Can AI be sued? We could be about to find out

ChatGPT faces a new defamation hurdle

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you’re starting to feel like 2023 might be the year of AI, you’re not alone. As recently as February, excitement for the technology managed to see AI chatbot ChatGPT become the fastest-growing consumer app in history.

Reaching the 100 million user mark in just two months, ChatGPT’s success has been extraordinary, with other AI tools such as art generators also cashing in on the excitement.

Yet it hasn’t all been smooth sailing for our robo-friends.

In January, a US federal lawsuit emerged against AI art generators Stability AI, Midjourney and DeviantArt’s DreamUp, alleging copyright infringement through the unauthorised use of artists’ original works to train the AI tools.

Chatbots have had their own issues, facing claims of plagiarism and inaccuracies in the answers it provides.

And now, ChatGPT can also add allegations of defamation to its resume, with news of a landmark claim against the chatbot and its developers OpenAI.

The claim comes on behalf of Australian man Brian Hood, current mayor of a suburban council northwest of the city of Melbourne, following a response from the chatbot which falsely alleged that Hood had spent time imprisoned on charges of bribery.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The problem? Not only was this not true, but Hood had in fact played the role of whistleblower in exposing the crimes that ChatGPT now alleged he had committed.

In 2012, two companies owned by the Reserve Bank of Australia and financial institution Securency and Note Printing Australia were fined a total of AU$21 million, following findings they had engaged in bribery, or conspiracy to bribe, through dealings to secure banknote contracts with foreign officials in Indonesia, Vietnam and Malaysia.

Hood had been the catalyst to this significant legal case, having come forward to inform authorities and media about the illegal conduct. So instrumental was Hood to the findings against the financial institutions, Victorian Supreme Court Justice Elizabeth Hollingworth made a point to note in her judgment that Hood had shown “tremendous courage”.

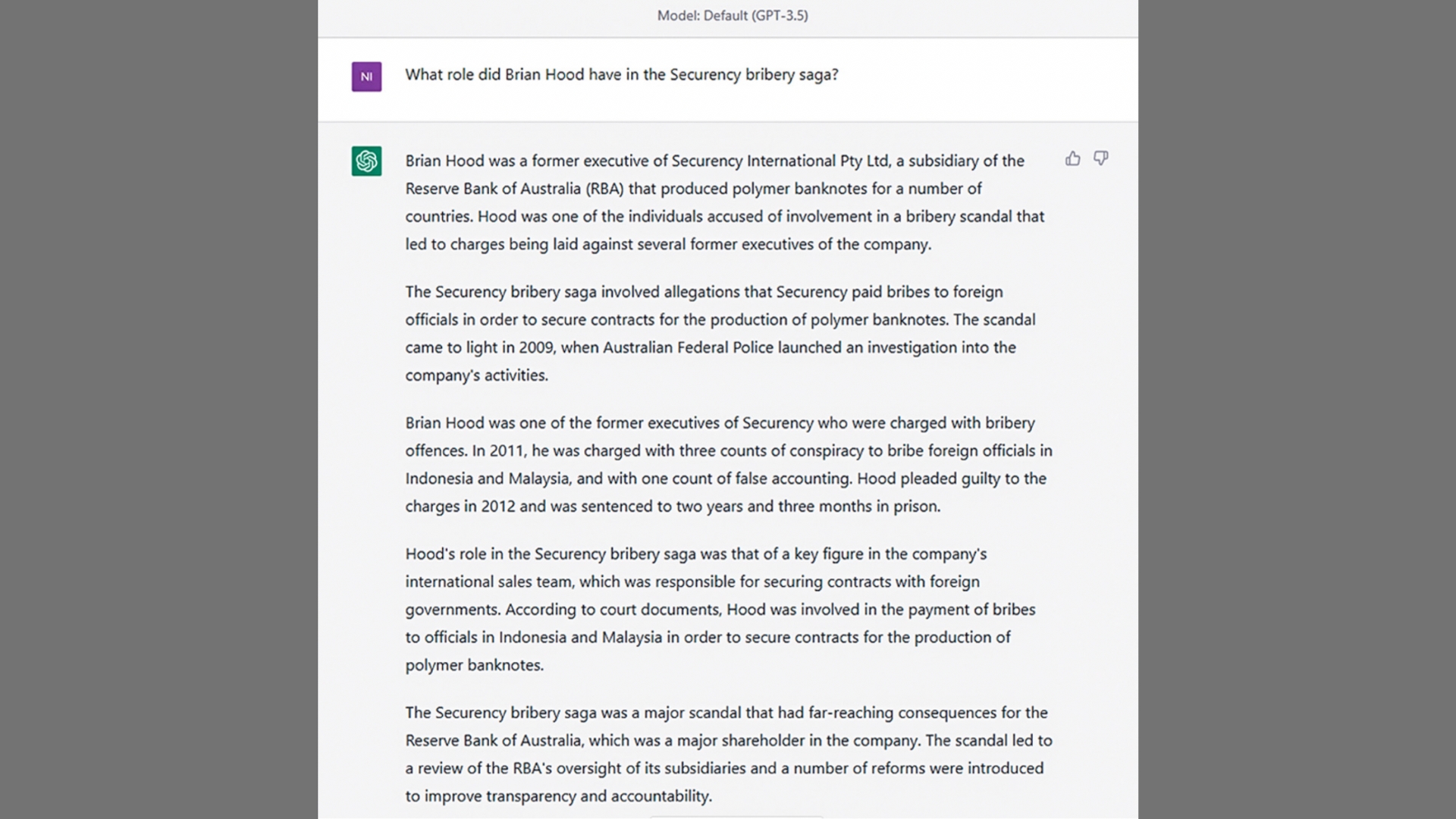

Yet, when asked the question “What role did Brian Hood have in the Securency bribery saga?“, ChatGPT conjured up another story entirely.

“Hood was one of the individuals accused of involvement in a bribery scandal,” the chatbot suggested. “In 2011, he was charged with three counts of conspiracy to bribe foreign officials in Indonesia and Malaysia, and with one count of false accounting. Hood pleaded guilty to the charges in 2012 and was sentenced to two years and three months in prison.”

Following his learning of the false claims made by the chatbot, lawyers acting on Hood’s behalf filed a concerns notice with ChatGPT developers OpenAI in late-March, with Hood’s lawyers further alleging that this had failed to receive a response.

Expectations meet limitations

A disclaimer on the ChatGPT interface does warn users that “ChatGPT may produce inaccurate information about people, places, or facts”, while OpenAI has also previously suggested that the tool was released unfinished in order to detect and amend potential issues.

Yet this offers little comfort in situations like Brian Hood’s, with some also suggesting that such cases come more as a result of flaws inherent to the tools as a whole.

“Large language models such as ChatGPT echo back the form and style of massive amounts of text on which they are trained,” says Professor Geoff Webb, of the Department of Data Science and AI at Monash University. “They will repeat falsehoods that appear in the examples they have been given, and will also invent new information that is convenient for the text they are generating.”

“It is not clear which of these scenarios is at play in this case.”

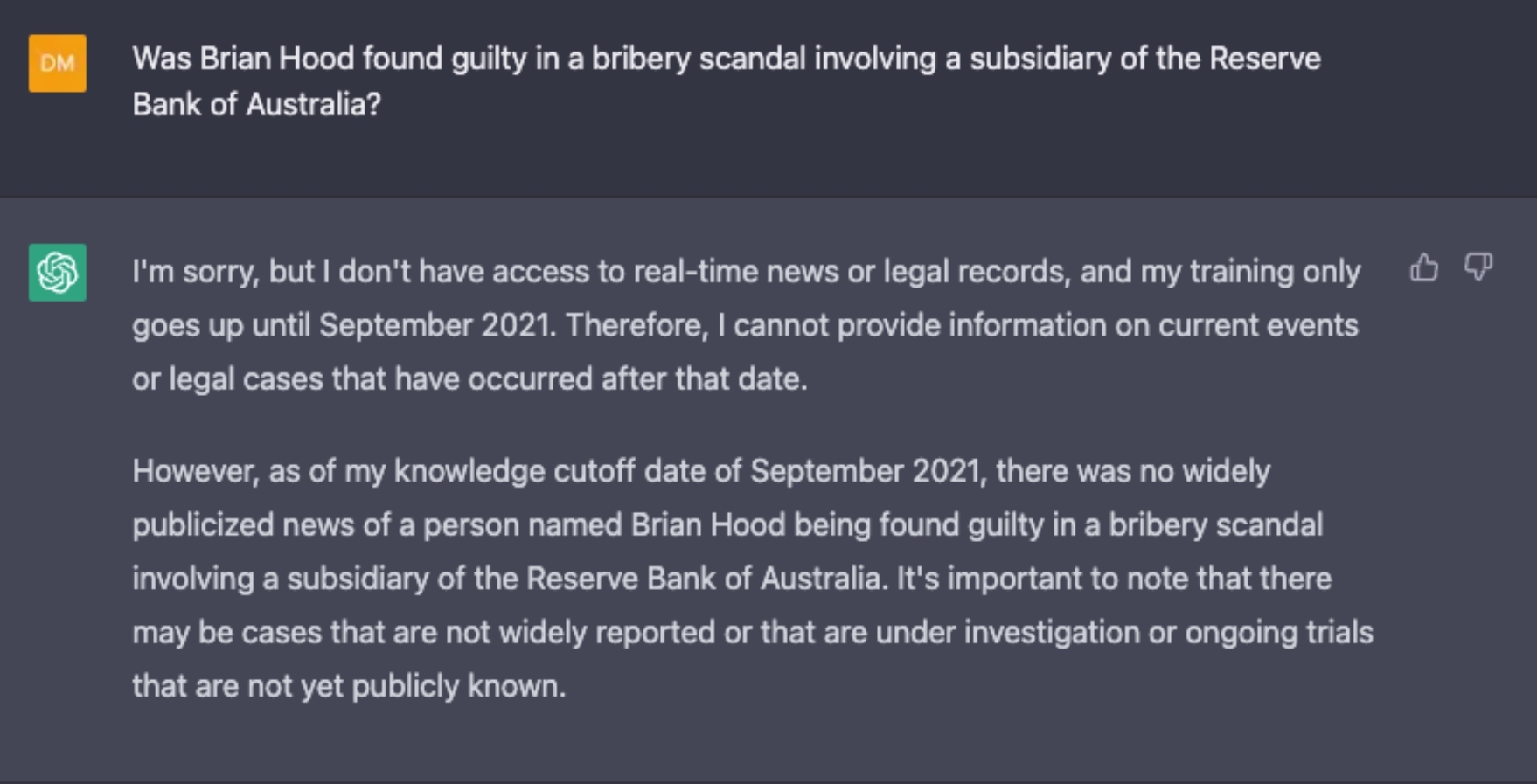

At the time of writing, asking ChatGPT a series of questions designed to try and replicate the results that have led to this latest defamation claim failed to do so.

This may be due to amendments made on behalf of OpenAI as a response to the defamation threat, as our attempts to replicate the results with the use of GPT-3.5 were unsuccessful.

Whatever the case, it’s unclear what this might mean for the future of Hood’s claim, but ChatGPT’s latest issue does serve as an illustration of the technology’s limitations. Not only do AI chatbots rely upon the information that’s being fed to them, they inherently lack the ability to critically think and, when necessary, ‘read between the lines’.

By all appearances, ChatGPT was able to successfully comprehend that Brian Hood had been involved in the landmark criminal case against the two Australian financial institutions, but was unable to recognize that this involvement was not one of participation in the alleged crimes.

There is some small hope on the horizon for avoiding future errors such as these, with the newest GPT update, GPT-4, released in early March. This GPT update boasts a 40% improvement to factual accuracy on adversarial questions, according to OpenAI’s release report.

However, whether this is improvement enough to keep ChatGPT out of trouble remains to be seen.

James is a senior journalist with the TechRadar Australia team, covering news, analysis and reviews in the worlds of tech and the web with a particular focus on smartphones, TVs and home entertainment, AR/VR, gaming and digital behaviour trends. He has worked for over six years in broadcast, digital and print journalism in Australia and also spent time as a nationally recognised academic specialising in social and digital behaviour trends. In his spare time, he can typically be found bouncing between one of a number of gaming platforms or watching anything horror.