How to improve your PC's audio output

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Music may be the food of love, but PC owners are still going hungry unless they opt for à la carte audio.

The wonderful thing about buying a new PC is that even the cheapest, Atom-based nettop is more than powerful enough for most of our daily tasks, and has enough hard drive space to keep Halliwell in HD happiness for a year.

The worst thing is that, although the PC is now our de facto source of music and video, even the most expensive ones come with speakers that make everything sound like it's coming through a telephone line. It doesn't have to be this way.

By sticking with the speakers their PC shipped with, people are settling for not just second best but downright awful audio.

However, good quality speakers really aren't that expensive any more – and they'll make an enormous difference to how much you enjoy music, games and video. It's one of the best investments around.

Preparing the ground

Before sound gets to your speakers, though, it has to go through your PC, and Vista is one of the biggest roadblocks to better sound performance.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Around the time of its launch there was a lot of controversy about the removal of Windows XP's DirectSound API, which was because it took away the computer's ability to shift fundamental audio tasks – like channel mixing – away from the CPU.

This primarily affected surround and ambient effects in games, which is why Creative Labs – which makes a lot of money selling soundcards with hardware acceleration – kicked up quite a fuss about it.

What this means in real terms is that if you have an old soundcard, such as an Audigy, you're not getting proper surround sound support in Vista. And that's just for starters.

Microsoft's reasoning

It's worth pointing out that Microsoft's reasoning for making the changes in Vista was solid; it was just its implementation that wasn't. There were two key reasons for getting rid of DirectSound.

First, Microsoft argued, sending raw audio for processing over the PCI bus to a soundcard was introducing more latency than allowing a fast CPU with plenty of spare processing cycles to run the same routines.

Slightly more convincing was the argument that sound drivers stank under XP and were a major cause of system instability. The new Vista model was even more extreme in its insistence on standards than DirectX10 was for graphics: so the Universal Audio Architecture should mean that most soundcards can run with high-end features like surround sound correction for speaker placement and jack detection without the need for third-party drivers.

That all sounds fine and dandy, but there were two key problems with removing DirectSound. One was that major changes were made to the architecture just before launch, affecting some sound chips that hadn't had recent driver updates.

The second is ongoing, and much more serious: processing sound on the CPU isn't quite as efficient as the Vista team hoped, and can introduce stuttering errors under high load.

This means the current situation for Windows is that every available soundcard will give pretty high-quality results, and any audio problems you do encounter are likely to affect them all.

Why opt for an add-in card?

Is there any reason, then, to even consider upgrading from an integrated soundcard to an add-in one any more?

For a lot of people, the answer is going to be no – onboard sound really is very good these days. There is still some justification to upgrading, though. Choose a good soundcard – Asus' Xonar range or Auzentech's Prelude, for example – and you will notice a difference.

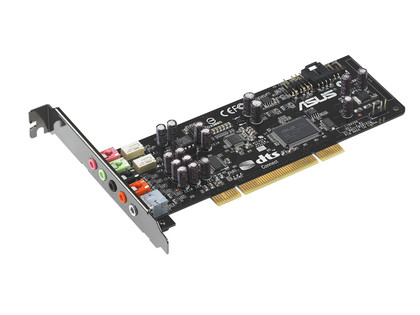

QUALITY AUDIO: Asus' Xonar soundcard rivals Creative's mighty X-Fi now that hardware acceleration doesn't change sound quality in Vista

For a start, there's more to sound processing than mixing channels and adding surround effects: an add-in card will often have amplifier circuitry that's missing from integrated chips.

They'll also have higher-quality components for a cleaner output with a wider tonal range during the process of converting digital sound to the analogue feed your speakers require.

It also means that you're putting distance between your audio processing hardware and the cramped electronics of the mainboard.

It's still the case that onboard sound can suffer from interference from other components in close proximity, especially on cheaper motherboards where sound is usually a secondary concern.

If you can hear the regular hum of a badly earthed jack or the occasional crackle, it's worth plugging a set of headphones into the same socket.

If the problems persist, chances are you're going to need an add-in board to get rid of them. That is, of course, unless you have a motherboard like Gigabyte's latest Media Live Diva. Not only does the onboard sound subsystem produce audio of a high enough quality to gain the prestigious THX Ultra2 certification, it also features an optional 100W digital amplifier that plugs into a spare PCIe slot.

There aren't many motherboards built to these standards, though: in fact, the only other one that springs to mind is Aopen's 2002 Intel 845-based model, which actually strapped a vacuum tube to the PCB for the rich, old-school sound favoured by connoisseurs. A noble endeavour, but wasted for listening to MP3s.

Staying onboard

Realistically, says Ryan Stuczynski, Logitech's European Product Manager for Audio, most people are happy to settle for a standard onboard sound chip.

The majority of new PCs sold these days are laptops, and even though there's a proliferation of USB soundcards designed to overcome the lack of upgrade slots in a notebook computer, it's not a massive market.

"People who do have a problem with onboard sound are the higher-end audiophiles," he says, "and they're solving that problem for themselves with component outputs and passthroughs."

In other words, if your computer has an S/PDIF or optical out, you'll get the best quality sound by taking the raw digital feed from the CPU via one of these outputs and using a separate amplifier with a built-in decoder for the grunt work.

- 1

- 2

Current page: Should you upgrade to an add-in soundcard?

Next Page Why you should buy new speakers