Content in moderation: is digital censorship messing with the arts?

The question of moderation does not start and end with the arts, of course. There has been mass outrage at Twitter removing tweets, for example. The number of government take-down requests made to Google have generally increased since the numbers were first reported in 2009.

Facebook, Instagram and any site publishing content has an obligation to remove harmful images and text, although where the line is drawn has always been something of a grey area. Swearing can seem like the least of the internet's problems; to try to stem the profanity online would surely give even the most determined algorithm a breakdown.

Before it moved to Disqus, TechRadar's own comment system used a similar approach to swearing as Clean Reader's. That's why, for a time, if you left a comment about a smartwatch, it was published as smart***ch.

The mechanics at work didn't understand that you were talking about the Samsung Galaxy Gear, it just thought you were calling us twats; sure, that could have been solved by a full word only clause, but the point is that the context is never taken into account. There is a world of difference between a comment tossed online and a published work that the writer agonises over for years but it can still obscure your meaning even when your meaning was inoffensive.

Facebook, YouTube and other high-volume websites use a mixture of automated processes and people to "keep dick picks and beheadings" out of the average person's line of sight. Wired's expose on the moderation farms published in late 2014 shone a light on the problems that this can cause.

Commercial content moderation (CCM), where companies are set up to offer human moderation as a service, is not exactly hidden by the big internet companies, but it isn't exactly raved about either. Possibly that's because of the potential health problems of repeatedly and continually exposing people to video and images of bestiality, violence and gore.

Sarah Roberts, Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Information and Media Studies (FIMS) at Western University, is one of the few people to have studied online content moderation from an academic standpoint. "The long-term effects of such exposure have yet to be studied (these moderation practices, organised into commercial content moderation among several different industrial sectors, are a relatively new phenomena)," she told us. "Certainly the short-term effects aren't great, either. People suffer burnout, or go home thinking about the terrible content they've viewed. Perhaps even worse yet, in some cases, they become inured."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The difference between using a machine to moderate text and images versus using a person to make a judgement call is vast. "Commercial content moderation is a highly complex and sophisticated task that calls upon a number of different faculties, including cultural, linguistic and other bodies of knowledge, as well as the ability to adjudicate based on a variety of policy issues as well as the much less tangible matter of taste. For those moderation tasks that are driven algorithmically, the content is often fairly simplistic (e.g., text comments).

"Humans are needed for intervention that computers simply cannot reproduce, and that comes in pretty much at any level beyond the most basic, and certainly where images and video are concerned," she added. To suggest that literature is basic enough to be moderated by a machine is something approaching an insult to anyone who ever studied a book at school or university, or made a career from studying or writing novels.

While no one has yet actively studied the effect of moderation on what people create and publish online and digitally, Roberts suggests that it is an area that is "ripe for investigation". Although Facebook, for instance, now publishes quite comprehensive community standards and has an expert team overseeing the process, the act of moderating content is not discussed or done in plain sight. "How would people respond if they knew the mechanisms by and the conditions under which their content was being adjudicated and evaluated?" asks Roberts. "How does that influence our online environment, collectively? And what does it mean when the sign of doing a good job of [content moderation] is to leave no trace at all?"

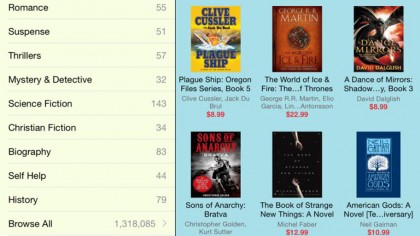

The questions outweigh the answers. How do we know if the humans working in content moderation farms are deleting photos of Michelangelo's David or other classic nudes from Instagram or Facebook? Why does Apple get to decide what nude photography is art and what is porn? How do we know if Netflix has removed a scene from a film? How do we know if an ebook service has changed the way we interpret a book simply by removing a swearword or underlining a popular phrase? What's to say all of these tiny moderations aren't working together to change the way art is created, appreciated and enjoyed?

We don't yet know what damage moderation, automated or otherwise, could be having on the arts. We have become accustomed to film, music and literature being thoughtfully processed by bodies like the BBFC, publishers and radio stations, and are generally aware of what has been cut, what has been deemed unacceptable and why. This provides not only a framework to work within but also something for provocateurs to rail against. The internet provides a vast opportunity for distribution, but an even bigger one for anonymous and unjustified editing.

The morally outraged cannot trust algorithms to do their job for them. It takes a village to raise a child and it takes whole industries to publish music, films, literature and any other type of cultural artefact. To then take these carefully crafted pieces of work and shove them through an automated process is not only disrespectful; it simply doesn't work. CleanReader may have failed, Clean Films may have failed but there is still a determined number of people out there who want to make this kind of human-free cultural moderation work.

Authors like Melissa Harrison and Joe Dunthorne are certain that apps like Clean Reader won't change the way they write. Harrison told us, "What I won't do – and will never do – is write dialogue that doesn't ring true, or use anything less than exactly the right word in the right place." Dunthorne agrees, "I don't think it would change the way I write. Things far more important than swearing don't."

But how can we be sure that authors, filmmakers, musicians and artists of the future, creatives who have grown up with moderators assessing their digital output at every turn, will say the same?

Former UK News Editor for TechRadar, it was a perpetual challenge among the TechRadar staff to send Kate (Twitter, Google+) a link to something interesting on the internet that she hasn't already seen. As TechRadar's News Editor (UK), she was constantly on the hunt for top news and intriguing stories to feed your gadget lust. Kate now enjoys life as a renowned music critic – her words can be found in the i Paper, Guardian, GQ, Metro, Evening Standard and Time Out, and she's also the author of 'Amy Winehouse', a biography of the soul star.