Macs and malware: how real is the threat?

Why fresh reports of malicious Mac software have yet to hit home

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Recent reports of Mac malware make for troubling reading. Last year"s much-publicised Flashback (or "Flashfake") Trojan has reared its ugly head again, this time in a more virulent form.

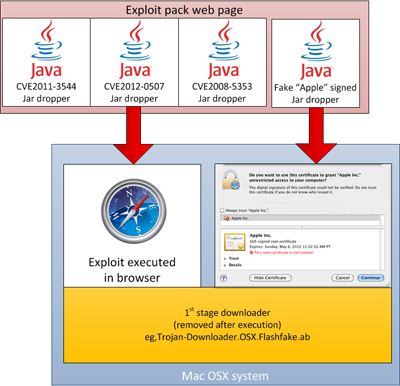

Where originally it relied on users okaying a bogus Adobe Flash Player plugin, now it hooks its tendrils surreptitiously into systems with a drive-by attack via compromised websites, hitting Java where it hurts.

Figures from anti-virus firms have been flooding in. Dr Web put the number of Macs infected at 600,000. Kaspersky promptly raised that figure to 700,000 and counting. "The idea that Macs are invulnerable is a myth," remarks Kaspersky analyst Vincente Diaz.

"This once again refutes claims that there are no cyber threats to Mac OS X," reports Dr Web"s Sorokin Ivan. The warnings from security companies are unanimous: Mac users need to sit up and take notice, because this is just the beginning.

But the tech community"s response to these reports has been anything but unanimous. For one, it"s proved great fuel for the Mac-versus-PC flame war, with PC people heralding the comeuppance of their arrogant Mac-using counterparts and Mac users proclaiming the relative security of OS X compared to any Windows version PC owners care to mention.

But look beyond the fanboyism and point-scoring and it"s clear that a significant portion of less partisan users remain unconvinced by the threat. Why? Because they"ve yet to see it for themselves.

Same old story?

But Apple-flavoured malware is far from a new phenomenon. In fact the first ever personal computer virus, Elk Cloner, was written for Apple II systems way back in 1982.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

While Elk Cloner didn"t cause deliberate harm and preferred instead to display a short poem to the user on every 50th boot, the viral proof of concept was born. An increase in bulletin-board and modem use saw the first PC virus show up in the wild four years later.

But it wasn"t until 1992 that the concept of the computer virus went truly viral. A US company called Leading Edge publicly warned that it had shipped 500 computers whose hard disks were contaminated with the "Michelangelo" virus. On 6 March, any computer harbouring this program faced having its disk data irretrievably garbled.

Latching onto the story, newspapers ran headlines in the next few days warning of imminent disaster. "Thousands of PCs could crash Friday," said USA Today. "Deadly virus set to wreak Havoc Tomorrow," said The Washington Post. By 5 March, the Associated Press was calling Michelangelo "a mugger hiding in a closet, waiting to ambush your computer".

But as George C Smith recounts in The Virus Creation Labs, this mass fear was the symptom of a new information overload – no-one seemed able to gauge what news was accurate and what was complete garbage. Meanwhile, fledgling anti-virus companies were only too happy to step into the fact vacuum and offer software to bring peace of mind to users and vanquish the perceived threat.

But when 6 March came and went without incident, no-one could tell whether they"d been had. Many anti-viral software vendors and some reporters insisted the coverage had prevented thousands of computers from losing data. But when USA Today tried to track Michelangelo, it could find only a few thousand afflicted computers worldwide.

Security consultants openly disputed the warnings of certain antivirus companies, while the latter blamed media outlets of inflating the threat because it made for a good story. So who exactly was to blame?

Viral legacy

In hindsight, everyone involved in the 1992 Michelangelo scare was responsible for hyping the headlines. But if anything the incident highlights why Mac malware reports often still fall on deaf ears. No-one disputes reports of PC viruses because so many Windows users have been their victims, but the same can"t be said for users of OS X – or at least not yet, anyway.

That"s because most reported Mac "viruses" actually turn out to be Trojans. These Trojan programs have relied on "social engineering" to infect computers, by masquerading as legitimate updates which tempt users to install them. Unlike destructive viruses, they don"t call attention to themselves, and instead recruit Macs to a discreet "zombie army". Computers that form this botnet are then used to commit click fraud by creating web traffic from those Macs, which in turn boosts revenue from pay-per-click ads.

Recently we learned that the controllers of the Flashback Trojan botnet didn"t actually receive any cash in the end. Even so, another proof of concept has shown up in the wild. Botnets aren"t just good for click fraud, but can be used for various heinous ends - sending out spam, coordinating denial of service attacks and so on. Though they take time to create, with strength in numbers they can be formidable.

The 18-month-old BredoLab botnet, for example, counted 30,000,000 Windows machines in its ranks before the dismantling of 143 command and control servers in 2010 led to its demise. Does that mean we can expect similar numbers of Mac zombies in future?

The walking dead

Kaspersky certainly thinks so. "In 2011, Apple was estimated to account for over 5% of worldwide desktop/laptop market share," reports analyst Kurt Baumgartner. "This 15-year peak coincided with the first exploration by the aggressive FakeAv/Rogueware market targeting Apple computers, which no longer seems to be such an odd coincidence."

But while some say market share overwhelmingly impacts attacker motivation, others see a bigger picture. Security company F-Secure claims that Mac malware is more the result of opportunist "bubble economies" that produce new threats in fits and starts, which would account for stuttering reports of Mac malware in the media over the years.

But others point to the underlying OS architecture as the cause. Until only recently, Windows applications ran as administrator-by-default, making infection upon launch a simple affair. Macs however don"t allow such default privileges. Of course, that didn"t bother the latest strain of Flashback.

The botnet strategy has evolved and the threat level has increased with it. By injecting malware into Wordpress plugins, cybercriminals are now launching drive-by attacks on Java vulnerabilities, bypassing the need for user activation so that Mac users don"t even know they"ve been zombified.

Naturally anti-virus companies were the first to alert the Mac community to this. But so far Apple has been unwilling to work with them – just as they"ve been unwilling to collaborate with Java programmers Oracle to plug the necessary holes.

This has left Apple slow to respond to the threat and open to criticism. Speaking to the BBC, Rik Ferguson, director of security research and communication at Trend Micro, notes how "Security updates issued by Apple are issued too slowly and not on any regular schedule.

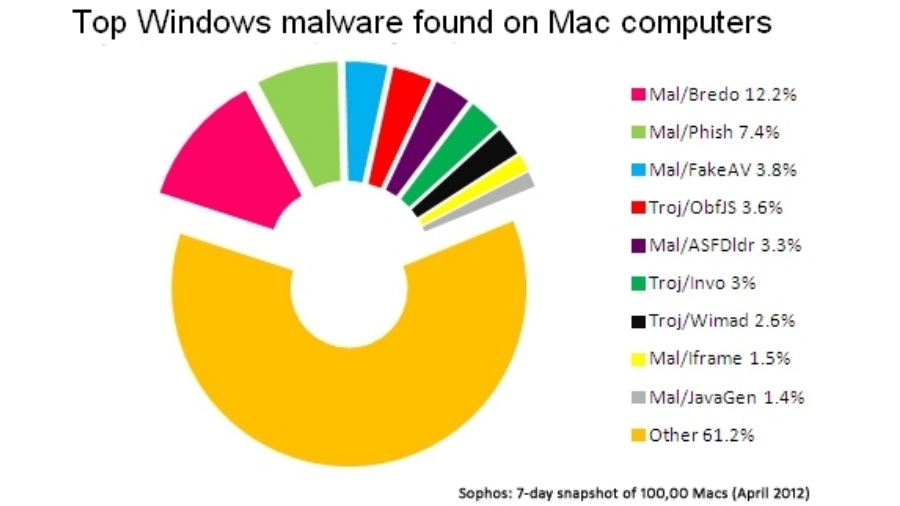

"Apple"s sluggishness on security updates could perhaps have been defended in the past by the relative paucity of malware on that operating system," he continues. "However, Mac OS is increasingly attractive and increasingly exploited by criminals." Still, a Sophos security report [one in five Mac systems has malware on it] confirms that Macs pick up far more Windows than they do Mac viruses, often through email spam and browser cookies, which can then be unwittingly passed onto PC users. Whatever the merits of Mountain Lion, its lockdown approach to security – dubbed Gatekeeper – will be useless against these.

For now, this remains the strongest reason for Mac users to install some sort of antivirus software, if anything to cultivate the mindset that malicious software is really out there. Because it won"t be long before the Mac-specific threat takes yet another twist. Let"s just hope Apple wakes up to its responsibilities before the next volley of OS X malware hits Mac users" shores.