Artificial emotion: is giving robots feelings a good idea?

A human touch too much?

Main image: SoftBank Robotics' Nao is currently up to its 5th version, with more than 10,000 sold around the world. Credit: SoftBank Robotics

Robots are being built for all kinds of reasons, from becoming stand-in astronauts on the International Space Station to the friendliest retail assistants around, and because many will work alongside and communicate with us, they need to understand, and even possess, human-like qualities.

But for robots to truly understand us, interact with us, and get us to buy things from them, do they need to have emotions too?

Science-fiction and the sensitive robot

Robots that can understand emotions, and even feel for themselves, have become a popular trope within science fiction – Data exploring his inability to feel emotions in Star Trek: The Next Generation, Ava manipulating human emotions in Ex Machina, and Samantha the AI software in Her breaking a man’s heart after she loves and leaves him.

We may still be a long way from creating robots with a nuanced grasp of human emotion, but it’s not that difficult to imagine how it could be possible.

After all, more and more of us are forming an emotional connection to Alexa and Siri, and the capabilities of such AIs are limited right now to simple interactions, like telling us what the weather’s like and switching our lights on and off.

Which begs the question: how much deeper could that emotional connection go with a robot that not only looks like a human but feels like a human too?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Programming AI and robots with a human-like grasp of emotion is a key area of robotics research and development. Companies like SoftBank Robotics and Hanson Robotics have already created robots that, to some degree, can read people’s emotions and react to them – or at least it's claimed they can.

SoftBank Robotics has built a number of robots that are, as the company describes, 'human-shaped'. Pepper is the one that has garnered the most media attention, with SoftBank claiming it can perceive emotions via facial recognition, vocal cues and body movements, and respond to them by serving up relevant kinds of content.

This is fairly basic compared to the robots of our sci-fi stories, but Pepper (and his many brothers and sisters) is already being implemented in SoftBank mobile stores in Japan. And he’s just one of the first in a line of robots that are being created to engage with humans on deeper levels.

The complicated mess of feeling feelings

Philosophers, psychologists and neuroscientists have been interested in what emotions are and why they’re so important to us for centuries. There are many schools of thought about what emotions really are, and why we experience them.

Cognitive appraisal theory suggests that emotions are judgements about whether what’s happening in our lives meets our expectations. For example, happiness is if you score a goal in a team sport because you wanted to score a goal, sadness is doing badly on a test because you wanted to do well.

Another theory is based more on what’s going on in your body, like your hormone levels, breathing or heart rate. The idea here is that emotions are reactions to physiological states, so happiness is a perception rather than a judgement.

But regardless of which view you believe to be true, emotions serve a number of critical functions, including developing intelligent behavior and developing connection.

So it makes sense that for robots to become better assistants, teaching aids, and companions, and take on a number of service roles, they need to at least have a rudimentary understanding of emotion – and possibly even explore their own.

That’s all well and good, but emotions – whether they're based on perception and expectation – are distinctly human, so how do we begin to grow, program or even teach them? Well, it all depends on how you view them.

Darwinian theory would suggest we’re born with emotional capability. That means emotions are ‘hard-wired’ rather than learned. So to get robots to feel we’d need to replicate some of the biological and physiological processes found in humans.

Other researchers keen to better grasp the nature of emotions look to social constructivist theories of emotion, which point to emotional behavior being developed through experience rather than being innate.

This school of thought is more appealing to robotics researchers, because it suggests that we can ‘teach’ robots how to feel, rather than having to create an all-singing, all-dancing, all-feeling robot from scratch.

Is it possible to teach emotions?

If robots can learn to feel emotions, how do we go about teaching them? One way of programming emotions is to tie them to physical cues that the robot can already experience, measure and react to.

A 2014 study into the social constructivist theory mentioned above found that robots appeared to develop feelings that were linked to physical flourishing or distress. This was taught by being grounded in things like battery levels and motor temperature.

The robots could learn that something was wrong, and react accordingly if they felt low on battery and could then link that experience to a feeling, like sadness.

There have also been a lot of studies carried out in the area of facial recognition. A 2017 study involved building a facial recognition system that could perceive facial expressions in humans. The AI could then change its inner state (as discussed in the 2014 study above) to better show human-like feelings in response over time, with the aim of being to interact with people more effectively.

Making robots work for us

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. There’s no point in developing awesome, empathetic robots if their reactions aren’t quite convincing enough. On that note, welcome to Uncanny Valley…

First described by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in the 1970s, the term relates to the fact that research shows that as robots look more and more like humans, we find them more acceptable and appealing than a big lump of metal – but that’s only the case up to a certain point.

When they get to a point were they very closely resemble humans, but aren't quite identical to us, many people tend to react negatively to them. Then, if they look more-or-less identical to humans, they become more comfortable with their appearance again. That area where they’re almost human, but not quite, shows up as a dip – the 'valley' – in graphs measuring human responses to robots' appearance.

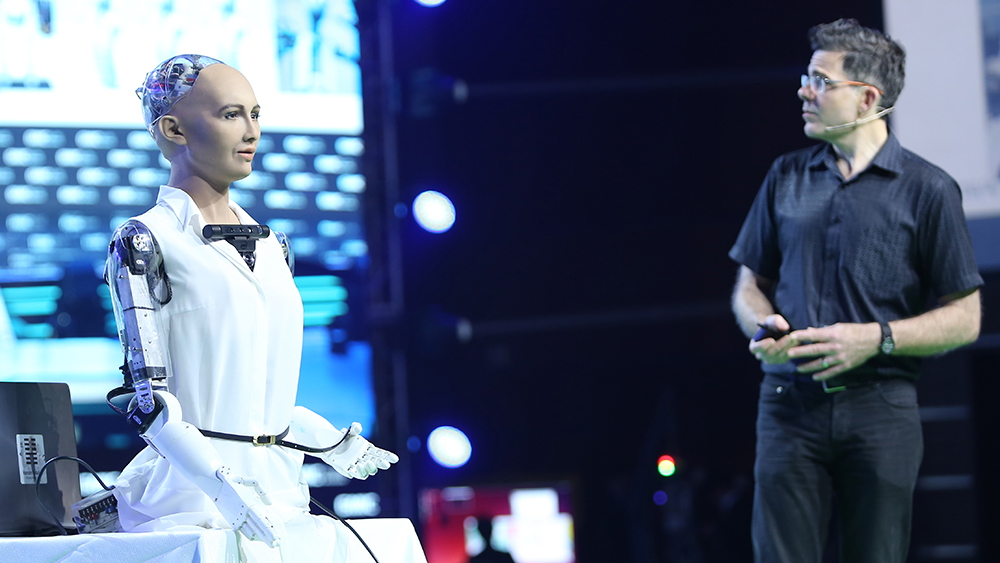

To get an idea of what we’re talking about, take a look at Sophia above, and tell us you’re not feeling a little freaked out. Developing a robot that doesn’t make our skin crawl, and which looks physically comforting, is just as important as developing one that can express emotion.

Building robots that love us back

So far we’ve focused on robots becoming assistants and carrying out service roles more effectively with the help of emotions. But if we’ve learned anything from sci-fi movies it’s that robots could also make awesome friends and, ahem, lovers. (Yep, we got this far without mentioning sex robots…)

A better understanding of emotions seems like an obvious prerequisite for companionship and potential romance, and already researchers are looking into ways that robots could, over time, not only learn more about us, but learn to depend on us as much as we depend on them.

In the 2014 study Developing Robot Emotions, researchers Angelica Lim and Hiroshi G. Okuno explained: “Just as we may understand a good friend’s true feelings (even when they try to hide it), the system could adapt its definition of emotion by linking together person-specific facial features, vocal features, and context.

“If a robot continues to associate physical flourishing with not only emotional features, but also physical features (like a caregiver’s face), it could develop attachment,” they wrote. “This is a fascinating idea that suggests that robot companions could be ’loving’ agents.

“A caregiver’s presence could make the robot ’happy’, associate it with ’full battery’, and its presence would therefore be akin to repowering itself at a charging station, like the idea that a loved one re-energizes us.”

But, as many of us know all too well, if we love someone and they love us back heartbreak could swiftly follow. Could a robot dump you – or could you be at risk of breaking a robot’s heart?

Love between humans and robots is a subject that's fascinating and unsettling in equal measure, and there have been lots of stories about how these relationships could go horribly wrong. For example, one recent study suggested that some people could be susceptible to being manipulated by robots. So the onus is on those creating robots to teach AI to use its newfound emotional powers for good, not for ill.

How sensitive robots could save the human race

It’s yet another popular sci-fi trope that robots might one day realize we humans aren't particularly impressive creatures, and decide to rid the Earth of us. It's a pretty far-fetched scenario – but what it you turned this idea on its head? What if, by training robots to experience emotions, we enabled them to develop an empathy with and understanding of us?

AI could use these emotions to develop morality outside of a standard rule-based system. So, although it might make sense to get rid of humans in some respects, robots could apply empathy to their reasoning, and would understand that mass extinction would cause humans pain and suffering, and that it would be nicer for all concerned if they just learned to put up with us.

Fingers crossed…

TechRadar's Next Up series is brought to you in association with Honor

Becca is a contributor to TechRadar, a freelance journalist and author. She’s been writing about consumer tech and popular science for more than ten years, covering all kinds of topics, including why robots have eyes and whether we’ll experience the overview effect one day. She’s particularly interested in VR/AR, wearables, digital health, space tech and chatting to experts and academics about the future. She’s contributed to TechRadar, T3, Wired, New Scientist, The Guardian, Inverse and many more. Her first book, Screen Time, came out in January 2021 with Bonnier Books. She loves science-fiction, brutalist architecture, and spending too much time floating through space in virtual reality.