Buying a cheap smart ring? Here's everything you need to know, including the risks

Why are there so many cheap smart ring clones online?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

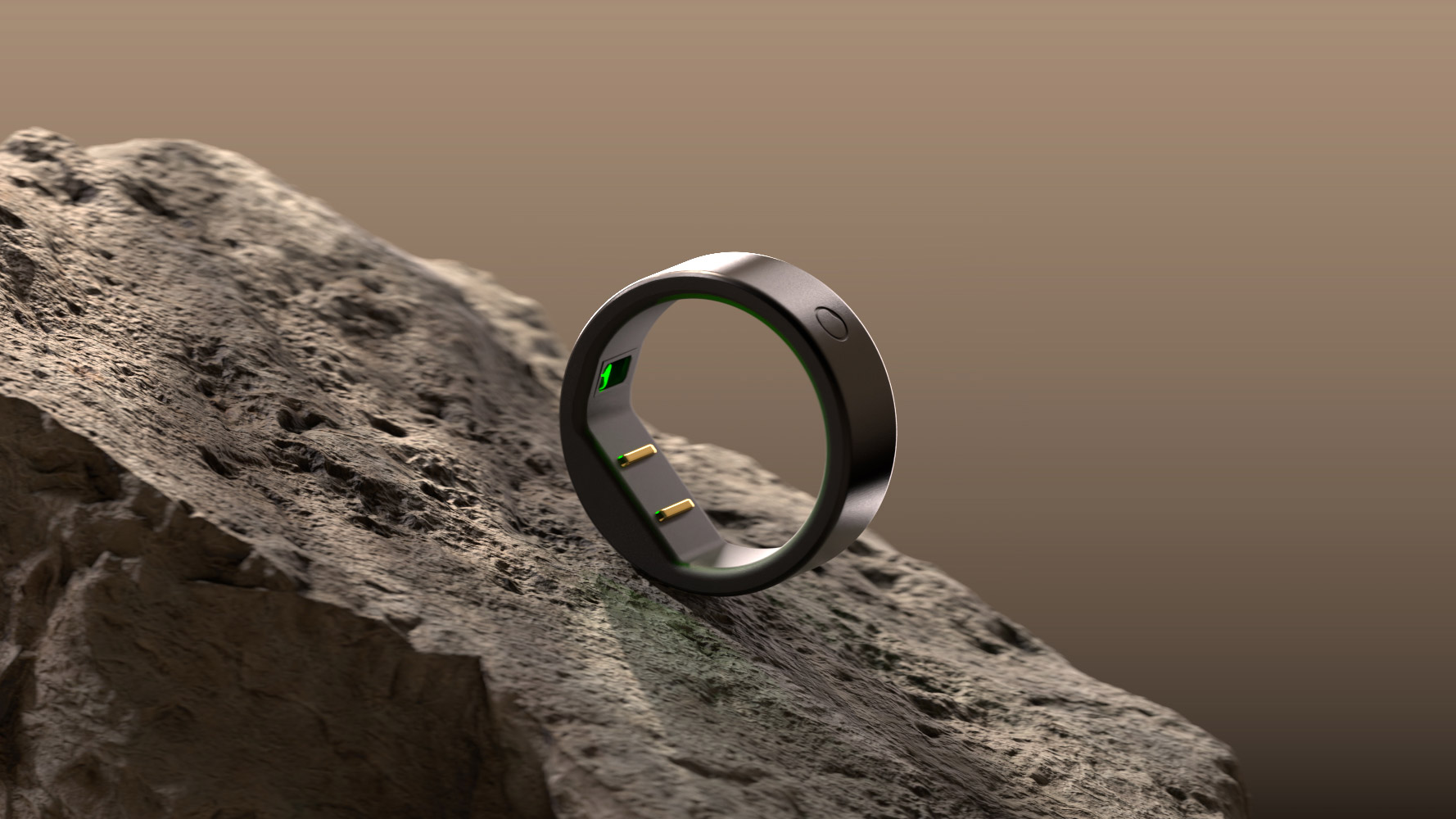

Smart rings are connected devices with sensors designed to collect lots of data about you, like your steps, sleep and heart rate. They’ve been around for a while; Finnish health tech company Oura released the first version of its smart ring back in 2015. Since then, several other brands have come and gone because creating a smart ring isn’t easy – a lot of tech needs to fit into a small space while still feeling and looking good.

They can also be hard to market. Companies need to convince people to take a risk on an unknown design rather than opt for a more affordable smartwatch or fitness tracker that can (for the most part) do all of the same things. But 2024 could be the year more companies get it right – Samsung is set to release its Galaxy Ring in late 2024, and there are rumors that even Apple is working on one, too.

However, as more brands enter the space and compete for our hands and our money, there’s been an influx of lower-quality, cheap smart rings that don’t clarify how their wearable tech works or who made it.

Article continues belowI’ve encountered several of these myself while reviewing them for TechRadar’s best smart ring guide, and I’ve been approached by brands that won’t divulge what their tech really does or where it’s from. Let’s take a closer look at what to watch out for and how to ensure you find the best smart ring.

Carbon copies: One ring, many brands

I first became suspicious of several smart ring brands when I was researching new devices and discovered a few looked eerily similar despite being sold by different brands. I wanted to know why, and my research led me to Art Parnell, an Enterprise Systems Architect based in Northern Virginia, US. He created the SmartRings community on Reddit, which is dedicated to sharing news and holding brands accountable.

“I push for the resolution of current smart ring issues and seek improvements with app UI and connectivity,” Art tells me. “This was initially to improve my personal experience with these devices, but now I use those connections to elevate broader community concerns.”

One of the big problems with smart rings is licensees, or clones. Generally speaking, this is when a company buys a wholesale product from a third-party manufacturer – in this case, a big batch of smart rings – and then brands them as their own. This happens much more commonly than you might think across various industries, including consumer technology. If you go to Amazon and look up fitness trackers, you’ll see many cheap devices from brands you may not have heard of, and there’s a chance several of these are from the same manufacturer.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Of course, many tech companies, including big players like Apple and Samsung, don’t create every component of their new devices themselves. However, there’s a difference between outsourcing the screen or processor of a TV, and buying the whole TV from someone else and sticking your logo on top of it.

Art calls these licensees ‘clones’ and tells me he’s dedicated to weeding them out. “I ended up creating a ‘cheat sheet’ image so that someone could recognize the most prevalent examples at a glance,” he says. “This has had mixed reactions from people loyal to one of these devices. But, most of the time, they have not even compared the device they own to another.”

It might be easier to spot clones if you’re buying a fitness tracker for your wrist, but because the smart ring market is so new, it seems that buyers aren’t doing their due diligence. They’ve just taken a new brand’s word for it.

Why would a company sell a clone? “I believe many of the licensees are just trying to take a shortcut into the smart ring space,” Art says. “Why invest in R&D when you can just buy a commercial device at wholesale and just start raking in the money?” He tells us that some companies may buy these smart ring clones for legitimate reasons, but they do it without realizing how many other companies have also licensed that same device.

The result? A whole load of rings that look the same with slightly different branding. Maybe some people won’t care; they like their new ring, the app looks nice, and everything works. But when I started reviewing one and asked the company whether it was licensed or not, they wouldn’t give me an honest answer.

Health data concerns

Art says there are also other reasons why the company not actually ''owning'' the ring and its app can be a problem. “Licensees do not always have access to the data in their companion apps,” he explains. “Instead, some are only granted the perception of ownership with a space for their branding, perhaps a registration page, and sometimes control over the color palette.”

This is a concern for users who may think their data isn’t being stored on-device or on company servers. Health data is extremely valuable, and should remain confidential. Most legitimate companies take data privacy very seriously. However, if the ring is a clone, it could be sending the health data it collects to an unknown company for unknown purposes. You'd have to read the fine print to know it, and even then it's not clear.,

The prevalence of smart ring clones isn’t the only problem Art has noticed over his years running the SmartRings Reddit community. He says the more rings that are being rushed to market, the more companies seem to be cutting corners.

“So many of the rings that are emerging highlight their overall features and analysis, without really seeming to care about accuracy,” Art explains. “ But, accuracy should be the foundation.” He uses the example of stress, saying that several smart rings market their stress-tracking capabilities, but that’s not something they can measure directly yet. Instead, it’s algorithms paired with heart rate data. Yet that may not account for other non-stressful situations that might increase heart rate, leading to misleading results.

He also has an issue with how smart rings are sold as providing personalized insights and recommendations, but the baselines used to make recommendations are often too general. Not considering things like non-traditional sleep schedules, shift workers or mothers tending to babies. “It's a reasonable expectation that when people buy these rings to help them monitor their own health, that it should be exactly that. Not how your personal baselines contrast with arbitrary baselines that don't factor in these variances,” he explains.

Some of these concerns are problems we've faced when assessing the accuracy of fitness and health tracking tech more generally, not just smart rings. But this doesn’t always come across in the big, bold ways they’re marketed. “Smart rings are not medical devices,” Art says. “But that doesn't mean they should get a free pass on accuracy.”

Why honesty is the best policy for smart ring manufacturers...

Art says another problem concerns customer expectation, especially given that many smart rings are crowdfunded or have faced technical difficulties. Delivery dates slip and devices don’t always look the same as early press photos. “Those who are the most vocal critics just don't understand how crowdfunding works. Or they only have limited experience with it,” Art says “Crowdfunding platforms are not stores!”

But this problem, and most others, can be addressed by more transparency from smart ring brands every step of the way. “If [a company is] licensing a ring, be honest about its capabilities, and don't imply or directly say that the device is made by (company country) and it is their own invention,” Art says.

The same goes for marketing claims. “Sometimes, through no fault of their own, the internal or outsourced marketing teams that companies use are often deceptive,” Art says. For example, if you say a ring is the thinnest in the world and cite specific numbers, those numbers better be right.

"Many of these products are being developed by people who don't have experience with communications… But the better they’re able to communicate honestly on a regular basis, the more people trust them.”

...And why patience is a virtue for smart ring buyers

The research firm Exactitude Consultancy predicts the smart ring market may balloon from $314.52 billion in 2023 to $2,570.30 billion by 2030, a 718 percent increase. This means more and more new devices will be hitting the market, and anyone who wants one will need to be wary.

Art’s Reddit community is a good place to start, but finding the best smart ring still requires you to do your research, which isn't easy for everyone. “You need to verify that the company is legitimate and that the device they’re pushing is not only something unique that they’ve developed on their own, but also that their claims are realistic,” he tells us. It’ll be no surprise if people default to the big brands that have already had a lot of press interest, which means smaller brands that are genuinely creating innovative new devices could miss out.

He also tells us that people need to be wary of reviews that aren’t honest, even on Reddit communities and tech sites. “It’s a disturbing reality and part of the reason that I created the SmartRings community,” Art says. He tells us that many companies have dedicated communities, which he says have become “echo chambers of praise”. In contrast, he tries to make his community as honest as possible. “I allow company representatives to interact with posters, and I flag them as company reps so there is full transparency,” Art says.

As with all new tech developments, taking it slow and doing your best to scrutinize bold claims is the best – albeit not the easiest – advice. “Don’t take marketing hype at face value. Dig deeper, and you might find your way to your ideal device.”

Art says he’d advise most people to wait until a device is out on the market and has been tested by multiple people, even though it can be hard to wait. “Early adopters like myself know to take everything with a bit of scepticism and know that much of the time, the promises will not match reality,” Art tells us. “But everyone isn't wired to accept this, and most don't want to ‘invest’ time and money into something that may not pan out.”

You might also like

Becca is a contributor to TechRadar, a freelance journalist and author. She’s been writing about consumer tech and popular science for more than ten years, covering all kinds of topics, including why robots have eyes and whether we’ll experience the overview effect one day. She’s particularly interested in VR/AR, wearables, digital health, space tech and chatting to experts and academics about the future. She’s contributed to TechRadar, T3, Wired, New Scientist, The Guardian, Inverse and many more. Her first book, Screen Time, came out in January 2021 with Bonnier Books. She loves science-fiction, brutalist architecture, and spending too much time floating through space in virtual reality.