How to watch and photograph tonight's Perseid meteor shower

It could be a stellar opportunity to watch (and snap) the Perseids

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Perseid meteor shower is one of the most impressive displays of shooting stars you'll see throughout the year – and it's peaking this week on the night of August 12 and early hours of August 13 in the US and UK.

The display of shooting stars, caused by Earth moving into the path of debris left by the Comet Swift-Tuttle, has been going since mid-July, but traditionally peaks on these dates every year – and that looks likely to be the case again.

That's because the Earth is moving into the most intense part of the comet's stream and ice and rock, which should produce an impressive light show for stargazers and photographers (weather permitting, of course).

Unfortunately, this year's Perseids peak coincides with a Sturgeon Moon, which reached its full phase on August 9. While it's now waning, it's still bright enough that it will impact visibility and make it impossible to see the maximum 100 meteors per hour, even in dark sky areas. The moon's brightness will be less of an obstacle on later dates, but by then the peak of the shower will have passed.

Observant and patient sky watchers, however, should still be able to spot a couple of blazing shooting stars each hour.

Whether you're looking to watch, photograph or livestream the celestial event, here's everything you need to know about this year's Perseid meteor shower.

When is the Perseid meteor shower?

The Perseid meteor shower is peaking this week, with the number of meteors hitting its main peak on the evenings of August 12 and August 13.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The best place to see the meteors is anywhere in the northern hemisphere in a dark location away from light pollution. Wherever you are, aim to head out on the evening of August 12 anywhere between 10.30pm – 4.30am.

According to the American Meteor Society, the absolute peak will be 4am UTC on August 13 (or 12am EDT / 9pm PDT, on the evening of August 12). But a high amount of meteor activity is expected for around eight hours either side of that peak, which is why you simply need to aim for the darkest part of the night.

According to NASA, you should be able to catch around 10 to 20 meteors per hour in most regions of the US, assuming you're away from urban light pollution. That's not quite the 100 meteors per hour rate we've seen previously in some regions – blame the Sturgeon Moon for that – but higher rates are possible, and that still works out at one meteor every few minutes, so well worth staying up for.

In the UK, the Royal Observatory's Finn Burridge told the BBC that observers may only be able to see "1 or 2 fireballs per hour". He also recommends giving things another go this coming weekend. "After the full Moon is more likely the better time to view, since the Moon will rise later in the night, so I would recommend the peak nights as well as weekend of 16 and 17 August."

Naturally, the weather could still also affect visibility, so you'll need to check for cloud cover in your location.

Another influencing factor can be wildfires. In 2021, the Pacific Northwest wildfires produced higher than average amounts of cloud and smoke that affected Perseid visibility, with only California, Texas and the East Coast escaping. So it's certainly possible that this year's wildfires in Colorado, California and Canada could have a similar effect in some regions.

Where are the Perseid shooting stars?

To see the Perseids' fireworks you need three things: complete darkness (so find somewhere remote, or turn off all the lights in the back of your house), clear skies, and the patience to look at the sky for about 20 minutes unrewarded.

If you can manage that last one, congratulate yourself for being among the minority of Perseid watchers: you could then be rewarded with up to 40 shooting stars in the next hour.

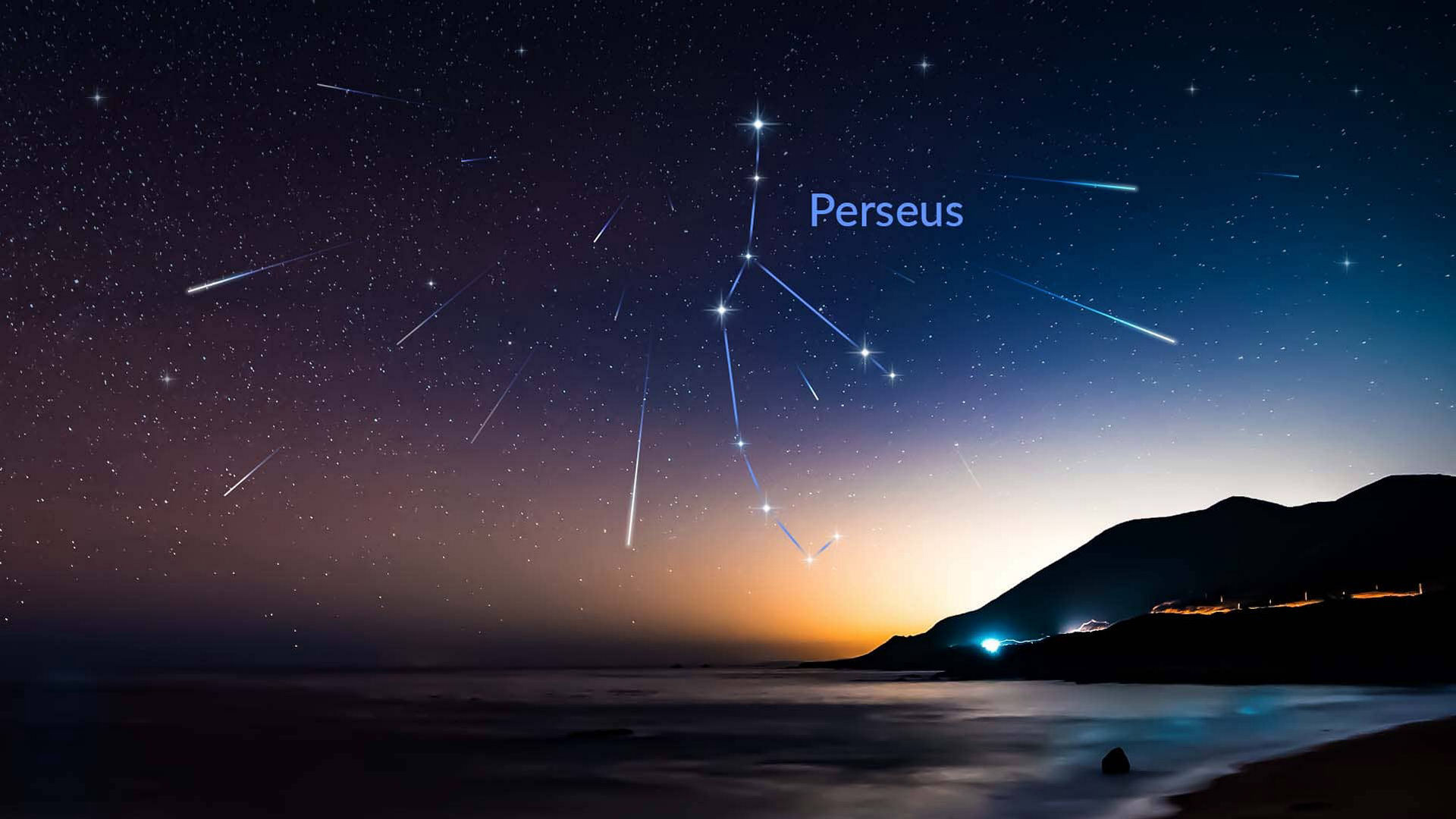

You could see shooting stars anywhere in the night sky, though as the name suggests they will appear to radiate from the constellation of Perseus – which means you just need to point yourself vaguely to the north or, if you're in southern latitudes, towards the north-eastern sky.

What do I need and what am I looking for?

The Perseids' meteors can show up in any part of the sky, so you'll improve your chances by finding somewhere with a wide view of the horizon – naturally, the fewer buildings and trees that are in the way, the better.

Most of its shooting stars will be visible for just a fraction of a second from the corner of your eyes. But every now and then, you'll also see big, bright, sparkling 'earth-grazer' fireballs that often appear to leave a trail behind them, and should last a full second or so.

A little patience (and a rucksack full of snacks) is advisable though – it can take your eyes at least half an hour to adjust to the night's darkness.

Resist the temptation to look at your smartphone or go back inside your house – every time your eyes see white light, your night vision goes back to zero, and you will have to wait another 20 minutes for it to return.

If you're venturing out, a torch with a red light can help preserve your night vision. The USB-rechargeable Petzl Actik or the cheaper AlpKit Gamma III remain good choices.

Aside from this and a comfortable blanket or sun lounger, though, that's all you really need – avoid a telescope or pair of binoculars, as these will limit your view of the night sky so much that you won't see any shooting stars.

Settle in for a good two to three hours, though, and you should be treated to an impressive show – even if the weather and moon do intervene.

How do I find Perseus?

If you're unfamiliar with the night sky at this time of year, there are a plethora of planetarium apps for phones and tablets. Use them sparingly, but apps like Star Walk 2 will help you find you the constellation of Perseus, which is just below the W-shaped constellation of Cassiopeia.

Fix your gaze on this patch of sky, and above, but don't get dogmatic about it: a meteor might just as easily start above your head and whizz south. However, to look low to the southern horizon would be a mistake.

You'll probably notice the massive Summer Triangle nearby in the eastern sky – three very bright stars that sits across the Milky Way. Stay outside long enough looking for meteors and your eyes may get sensitive enough to glimpse this wonderful sight.

Are there any Perseid meteor shower live streams?

While there aren't quite as many Perseid livestream opportunities on YouTube as there were during the pandemic (when large observatories like the Lowell Observatory in Arizona hosted online viewing sessions), the The Virtual Telescope Project does have an online observation planned for August 12, starting at 21:00 UTC.

How do I photograph the Perseids meteor shower?

When it comes to photographing the Perseids, there is also a large element of hit-and-hope involved. Despite huge improvements in smartphone astrophotography modes, their sensors still generally lack sensitivity for shooting meteors. What you need is a DSLR or mirrorless camera (ideally a full-frame model) with manual controls, mounted on a tripod.

The setup

Choosing the right lens and focal length is a bit of a balancing act. Generally speaking, the best astrophotography lenses tend to be pretty wide, in the 14-20mm focal range on a full-frame camera (or around 10-14mm on an APS-C model). On the other hand, Perseid meteor trails can look pretty small and sometimes barely visible when shooting that wide.

As you're unlikely to be buying a new lens just to photograph this meteor shower, we'd recommend grabbing whichever lens you have that's closest to the 28-50mm range (or 17-32mm on APS-C cameras).

The Perseid meteors can appear pretty much anywhere in the sky, so it's best to find some foreground interest for your shot – like a tree or, even better, a decommissioned antenna like the ones at The Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory in the UK (above).

The settings

Switch your lens to manual focus and set the focus to infinity – or point it at a bright star and manually focus on it. Set your ISO to 800 and your aperture to f/2.8 (or whatever its widest aperture setting is, if it's above f/2.8), and take some long-exposure shots over 20-30 seconds. You'll need to either use your camera's self-timer or a remote shutter to avoid camera-shake and blur.

Check your test shots to make sure they're sharp and correctly exposed, making any tweaks if needed. Another option is to use your camera's built-in interval timer to shoot a timelapse, taking about 100 or more 3o-second exposures one after the other.

You can then use the likes of Photoshop or StarStaX (on Mac) to create a star-trail, which will (hopefully) have shooting stars all over the image.

You might also like...

- I spent a year with the $550 smart telescope that's shaking up the astrophotography world – and this is what it’s capable of

- I tried an entry-level AI telescope and all I learned is that tech doesn’t make everything better

- How to step up your stargazing game in 2025 on the cheap, according to space experts

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),

- Sam Kieldsen

- Mark WilsonSenior news editor

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.