Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With the existing internet, security is something that's largely been bolted on as an afterthought – but the FIA program expects security to be a key consideration from the outset. That's leading to some interesting ideas, including one security system that takes its cues from Facebook.

Davis Social Links (DSL) adds a "social control layer" to the network that identifies you not by your IP address but by your social connections. If it works – and DSL is in the very, very early stages of development – it could make a major dent in problems such as spam and denial of service attacks.

Eugene Kaspersky, CEO of Kaspersky Lab, would like to take things even further. In October, he argued that the internet's biggest weakness was anonymity, and that everyone should have online passports. "I'd like to change the design of the internet by introducing regulation – internet passports, internet police and international agreement – about following [web] standards," he told ZDNet Asia.

BORDER CONTROL: Should you produce your passport to get online? The CEO of Kaspersky Lab thinks it will improve security

Kaspersky explained further on the Viruslist.com blog: "When I say 'no anonymity', I mean only 'no anonymity for security control'," he writes, explaining that he couldn't care less what people posted on blogs or downloaded through BitTorrent. "The only [requirement] – you must present your ID to your internet provider when you connect."

Kaspersky argues that such requirements are inevitable, with some EU countries already introducing digital IDs. "Another prototype of e-passports is the two-factor authentication we use to access corporate networks," he says. "The only thing missing today is a common standard."

Security guru Bruce Schneier isn't convinced. "Mandating universal identity and attribution is the wrong goal," he writes on Techtarget. "Accept that there will always be anonymous speech on the internet. Accept that you'll never truly know where a packet came from. Work on the problems you can solve: software that's secure in the face of whatever packet it receives, identification systems that are secure enough in the face of the risks. We can do far better at these things than we're doing, and they'll do more to improve security than trying to fix insoluble problems."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The quest for improved security is attracting a lot of attention - and a lot of money. The US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) awarded contracts worth $56million in January to two firms as part of its National Cyber Range security programme, which will enable network infrastructure experiments, new cyber testing capabilities and realistic testing of network technology.

A month previously, Raytheon BBN Technologies was awarded an $81million contract by the Army Research Laboratory to build the largest communications lab in the US, again to research network security.

David Emm is part of Kaspersky Lab's Global Research and Analysis Team. "It would be unrealistic to expect a wholesale re-architecture of the internet, or even of some of the technologies that are used online," he says. "If we fix the problem by removing the facility, we run the risk of damaging legitimate activity too."

There's also the issue of displacement: if the internet becomes tougher to compromise, villains will simply switch to social engineering instead. As Emm points out, corporate email filtering to remove attached '.exe' files simply spawned the use of links rather than attachments to spread viruses and other malware.

"There has always been a human dimension to PC attacks," he says. "Patching code is fairly straightforward once you know what you need to fix. But patching humans takes longer and requires ongoing investment."

The last mile

There's another big piece of architecture that needs upgrading: the bit between your ISP and you. Whether that's a wired connection or a wireless one, today's technology needs a serious speed boost.

As Tim Johnson of broadband analyst Point Topic explains, " Over the past 15 years or so we've seen the data speeds that typical home users get going up roughly 10 times every five years. I think that will continue over the next decade so that by 2020 many users will be getting a gigabit on their home broadband.

"The big barriers that must be overcome to get there are (a) extending fibre all the way to the home, and (b) providing the backhaul capacity and the interconnect standards to make it useful," he elaborates. "Both of those are do-able but I think it will be quite late in the teens before they are achieved."

Johnson reckons that things will get particularly interesting when 100Mbps+ connections are the norm, as they will be able to deliver immersive, high-definition environments and "a huge new space of technology, applications and lifestyle possibilities".

But he's not convinced the internet can even handle that – not in its current form, anyway. "This kind of application is rather different from what the internet was designed for and is good at," he says.

"From an engineering point of view it will mean provisioning capacity that will allow users to set up assured end-to-end symmetrical calls of at least 20Mbps each way. There also needs to be a huge amount of standards development and investment to support setup and switching. […] It's possible that this could all be done across the open internet, but my own belief is that as this type of traffic grows it will create the need for more dedicated capacity. IP and intelligent multiplexing will still rule, but the basic architecture will be different."

Going mobile

In developed countries, the internet is moving away from the desktop and onto mobile phones and other wireless devices, while in developing countries the internet is primarily a mobile medium already.

In both developed and developing countries the number of mobile internet users will increase dramatically in the next decade. So if you think the mobile networks are creaky now, things could get considerably worse in a decade.

For the mobile internet at least, the future may look an awful lot like the past. As Jon Crowcroft of the University of Cambridge writes: "We are so used to networks that are 'always there' – so-called infrastructural networks such as the phone system, the internet, the cellular networks (GSM, CDMA, 3G) – and so on that we forget that once upon a time (why, only in the 1970s) computer communications were fraught with problems of reliability, and challenged by very high cost or availability of connectivity and capacity."

Noting that technologies such as email coped fine in those conditions, Crowcroft suggests that, "It appears that it's worth revisiting these ideas for a variety of reasons: it looks like we cannot afford to build a Solar System-wide internet just yet, [but] it looks like one can build effective end-to-end mobile applications out of wireless communication opportunities that arise out of infrequent and short contacts between devices carried by people in close proximity, and then wait until these people move on geographically to the next hop. It's interesting to speculate that these systems may actually have much higher potential capacity than infrastructural wireless access networks, although they present other challenges (notably higher delay)."

Such systems – variously called Intermittent, Opportunistic or Delay Tolerant networks – have a wide range of applications. They're useful in emergencies and in areas where there isn't an existing network infrastructure, and they're particularly well suited to emerging applications where a constant signal can't be guaranteed, such as internet-enabled cars. While such networks could ultimately be deployed in remote areas, for most of us the future of the mobile internet is very similar to what we've already got.

LTE (Long Term Evolution) is a kind of 3G network with knobs on, and in the UK at least it's generating much more interest than the rival WiMax technology. When LTE begins to roll out later this year it will deliver theoretical speeds of up to 140Mbps, rising to 340Mbps after a 2011 upgrade. An even faster version of the network, LTE Advanced, is in the works.

It's worth noting, though, that even the first version of the LTE network will take several years to roll out nationwide.

And WiMax? In February this year, Patrick Plas – Alcatel-Lucent's Chief Operating Officer for Wireless – told reporters that the company "is not putting a lot of effort into this technology any longer" as mobile networks were showing "a clear direction taken by the industry towards LTE". That's an honest indication of where the mobile internet is heading.

Looking ahead

Predicting the future is a tricky business, and predicting the future of the internet is doubly so. However, it's clear that the next decade will see some dramatic changes in the way the web works.

Some changes are definite – the move to IPv6 will happen, albeit more slowly than many would like – while other developments such as opportunistic networks may never become mainstream.

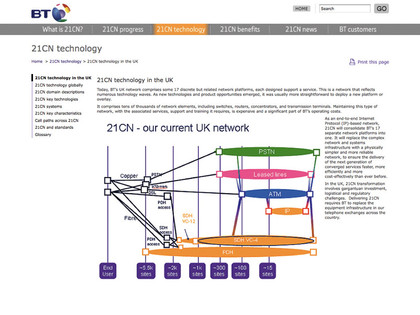

21st CENTURY: BT's 21CN project is a software-driven network that aims to drive innovation

What we can predict is that the internet of 2020 will be coping with user numbers and traffic volumes that we can barely imagine. To be able to cope with that, the net will probably become a hybrid: a mix of old and new.

As Falk puts it: "Recent interest in 'clean slate' network architectures encourages researchers to consider how the internet might be designed differently if, say, we knew then what we know now about how it will be used," he says.

"But that is not to say we must discard the current internet to fix the problems. The internet has tremendous value, has supported astronomical growth and changed the lives of millions of people. I believe research in new internet designs will provide insights on where the high-leverage points are on the current design thus allowing us to understand, justify, and deploy changes that will bring the greatest benefit."