Forget 3D: holograms are coming to smartphones

Incoming 'mixed reality' tech promises floating images and 3D calls on the small screen

Forget FaceTime – why not say hello with a hologram? Imagine making a holo-call on your phone, with a 3D image of the caller appearing to leap out at you from the phone screen.

"The basic idea of using hologram technology in a smartphone is that you would be able to project a 3D image into space at a certain short distance away from the device," says Waiman Lam, VP for global marketing at ZTE Mobile Devices, who told TechRadar that holo-phones are at the pre-research stage.

Since phone-makers are largely non-committal about the technology, ZTE's enthusiasm is a positive for anyone excited about holo-phones, but Lam admits that for the technology to be successful, image processing power, display capabilities and light conditions would have to combine perfectly.

"We estimate that it will still be at least a few years or more until we see hologram phones," he says.

What's the delay?

Think about holograms and it's likely your reference point is something like a Star Wars-style light projection you could physically walk around, as in "Help me Obi-Wan Kenobi, you're my only hope". If so then it's time to rein-in your expectations slightly.

"Technically the concept of a hologram is physically impossible, because you would need to stop a light beam at a point in space," says Karl Woolley, creative technologist at FrameStore, which is working with the super-secretive Magic Leap, a company that's working to create a 3D world by projecting images into your eye.

He explains that it's only when light bounces off something that we see brightness and colour.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

For now, the only way you can stop light and create a convincing hologram on a phone is by using a glass pyramid on the screen itself; the effect is pretty good, but it's hardly a pocket-friendly design. "It looks like the object is spinning in the air but it's not, it's just being projected and reflected," says Woolley.

Technically a holo-phone already exists

That said, it's already possible to see holograms on your phone using Virtual Presence units. "Viewers simply download or live-stream the relevant content, place their phone in the unit and press play, and a convincing hologram appears in front of them, floating in mid-air," says Sharad Kumar, Co-founder of Virtual Presence.

"It uses a patented design built around a miniaturised projection technique, using your smartphone and a very robust, yet near-invisible material."

Putting your phone in a box? Hmmm… Not quite what we had in mind. However, there is another way: researchers at the Human Media Lab at Queen's University have demoed a prototype of their HoloFlex tech, which brings glasses-free 3D holograms to smartphone-based games, photos and phone calls, although sadly it's currently very low-resolution.

YouTube : https://youtu.be/UDOkwJTPgCc

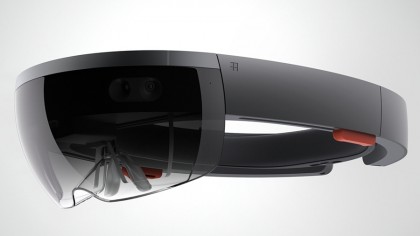

The concept of a holo-phone probably means re-thinking the idea of what a phone is. If you stop light with a screen or a filter, you can create holograms; cue the light engine inside Microsoft's HoloLens, which has already been demoed enabling a Skype call to a plumber.

"The plumber can see on their Microsoft Surface tablet what you're seeing on your HoloLens headset, and they will draw a circle on their tablet around the U-bend you need to tighten up, then they'll circle the spanner you need to use," says Woolley.

HoloLens augments reality; effectively the plumber can show you exactly what to do. "It's about communications, but it's not a phone as we know it," adds Woolley.

Given that the concept still feels more science fiction than a forthcoming product, many probably imagine hologram phones to be more like the VR worlds offered by Oculus Rift and HTC Vive, but HoloLens is subtly different.

"The key difference between virtual reality and augmented reality – or mixed reality, which is what HoloLens and Magic Leap are – is that in VR you can be placed into Game of Thrones, for example," says Woolley. "But with AR or MR, you could place characters from Game of Thrones into your existing environment."

As well as not being 'blindfolded', MR headsets (from Epson's Moverio, and Meta, as well as from Microsoft and Magic Leap) are transparent and, technically, create the illusion of a hologram from an on-screen image. Is this all a bit too like using polarised glasses to watch a 3DTV?

"3D is a simulation, holography is not," says Woolley, explaining that while 3D appears on a screen, holography appears in your space and is rendered not just as a left and right image, but through 360 degrees.

So is the concept of holo-phones merely a kind of augmented reality? "Augmented reality is more a data overlay designed to enhance our everyday lives contextually, while holography is an incredibly powerful way of engaging with visual content," says Kumar.

Beyond games and entertainment

However, the actual commercialisation of holo-phones depends on one thing. "It all comes down to consumer demand … do we need a holographic phone, and what purpose would it serve beyond games or entertainment?" wonders Woolley.

So if not into phones, where might all this investment in holograms go? One use is in cars, and Jaguar Land Rover is already using lasers to create a hologram-driven heads-up display on the windshields of its Range Rover Evoque vehicles.

The latter relies on a technology called dynamic holography, which was created by Dr Jamieson Christmas at Cambridge University a few years ago.

"Dynamic holography is a slightly different technology," says Dr Christmas, now Chief Technology Officer at Daqri Holographics, which specialises in AR displays.

"The core technology addresses the problem of how to construct a high-quality hologram purely by slowing light down as you pass it through a custom material," he explains. "It's not been viable until just a few years ago, because the mathematics behind it really are extraordinarily complicated."

So is this the missing link for holo-phones? Er, no. Christmas insists that modern phones just don't have the computational power to cope with dynamic holography. "Just to put the computation of holograms into perspective, to project a real-time, full-colour hologram takes about 150,000 million computations per second," he says.

"For mobile phones, power consumption and highly functional, very bright displays become critical, but the limiting factor is actually the modulators in phones, which are currently too coarse to achieve the kind of holographic image you would want to see on a mobile phone."

Still, a hologram phone is at least possible. "To look at your phone and perceive a 3D image either floating towards you, or to look through your phone to see a 3D image the other side … both of those things are possible, but not with the technology we have today," Christmas adds. "We would need a substantial advancement in the modulators."

The holo-phones we're talking about here are essentially small-screen holograms, which would command new technology for our handsets. "Built-in holography would require a small yet powerful enough projector to work in natural light, but also the ability to sustain an image in mid-air," adds Virtual Presence's Kumar.

"If you are interested in a totally 3D, volumetric image projected without any apparatus, the technology is still some way off … 3D phones still require glasses. That, and technology such as ours, are the closest to a true hologram today."

Could 5G help?

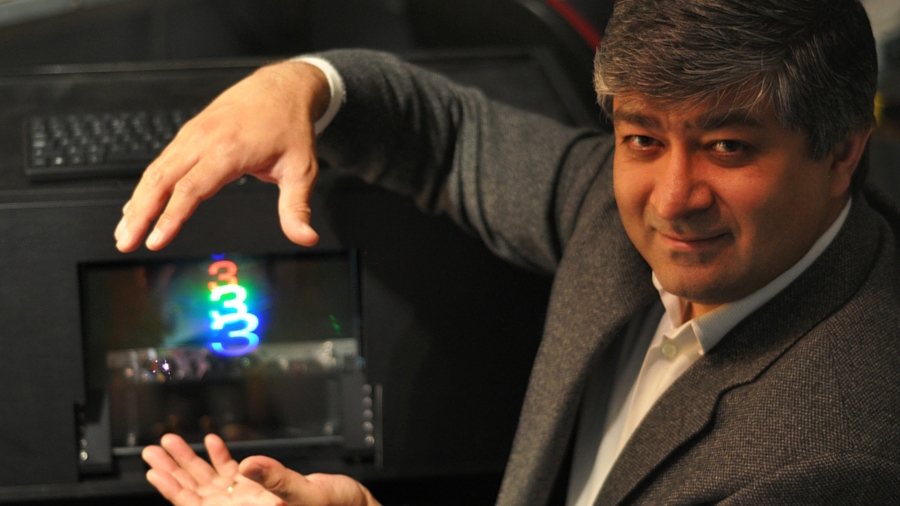

For hologram phone calls, bandwidth would need to increase, too. "A 3D moving image takes a lot of data, but in principle 5G phone networks should be able to handle the data rate, especially if it is compressed," says Javid Khan, founder of Holoxica, which specialises in 3D digital printed holograms and holographic 3D displays for medical imaging.

Although his company is creating true 3D holographic displays for use in medical imaging, scientific analysis, engineering design and architecture, he thinks hologram phones are some way off.

"The issue with a small device projecting a hologram is that the image has to be smaller than the device – this is down to physics – so a holographic display from a phone would be fairly small," he says. "A way round this might be to wear VR glasses, I guess."

A mixed reality future

In the world of holographic technology, and in mixed reality generally, there are a lot of concepts vying for adoption in devices.

An unknown quantity – and a possible game-changer – is Magic Leap, which has picked up investment from big companies like Google and Alibaba to develop a 'cinematic reality' technology that projects a digital light field into a user's eye, to create realistic images over the physical world. It's constructing a virtual retina display that superimposes 3D graphics onto real world scenes.

"The technology has the ability to accurately place objects and make them look like they're in your environment," says Wooley, who's working with Magic Leap. Called 'Dynamic Digitised Lightfield Signal', Magic Leap will still be hardware – some kind of head-mounted display will be needed to deliver the light – but it will lack a screen. Some think it's already got a market value of nearly US$3.7 billion.

"Magic Leap has an immense amount of money for retinal displays … maybe we could end up with gaming in real life, and there is lots of room for surprises," said Paul Gray, Principal Analyst/Researcher at IHS, speaking at IFA spin-off CE China in April.

However, from what little we know about Magic Leap, one thing is for sure: it will cut out the screen, effectively implanting content – even a computer's user interface – into our brains. It sounds like a step towards something totally new, perhaps even the Singularity.

There's a rabbit hole that's almost ready marked 'mixed reality', and holo-phones, holo-games and holo-movies will all play their part.

Main image credit: Holoxica

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),