Two years from now, something remarkable will happen: there will be more smartphones in the world than PCs. Technology analysis firm Gartner predicts that by 2013, there will be 1.82 billion smartphones compared to 1.78 billion PCs - and that doesn't include tablets.

Apple sold 14.8 million iPads in 2010, and Forrester Research says that in the US, 82 million people will own tablets by 2015. Tablets and smartphones have become incredibly powerful in a very short space of time, with gigahertz-class dual-core processors, decent amounts of RAM and high definition displays appearing in pocket-friendly forms.

As the price of such small but powerful devices continues to fall and hardware firms continue to innovate, it's clear that mobile computing is going to be a very big deal for the foreseeable future.

Mobile devices have been with us for as long as the PC. The first laptop, the Osborne 1, went on sale in 1981. Psion's Organiser came out in 1984, Apple's Newton appeared in 1993, the PalmPilot turned up in 1995, and 1999's Palm VII could connect wirelessly to the internet.

But while the basic shapes of mobile devices haven't changed much over the years, what's inside them has been transformed. Even the humblest smartphones are packing gigahertz processors, touch screens and Wi-Fi radios, and their prices are plummeting. So where is the mobile market heading?

The mobile mindset

Building mobile devices requires a completely different mindset from desktop devices. With desktops, manufacturers can more or less build what they like - installing the latest, fastest multi-core processors and graphics cards, adding gigabytes of RAM and terabytes of storage doesn't have a detrimental effect on anything but the price tag.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

With mobile devices, small changes can have a big effect: a bigger, brighter screen can make a smartphone too bulky, or dramatically reduce its battery life. While mobile processor speeds are increasing, the real challenges are in battery life and features. Slightly faster processors don't sell devices; doubling the display's pixel density, offering LTE connectivity or adding a better camera does.

With desktops, the biggest concern is power. With mobile devices, it's portability. Take a smartphone, for example: remove the battery and the screen and you've got a tiny amount of space - space that needs to include not just a processor, storage and RAM, but multiple radios (for 3G, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth), a SIM card slot, circuitry for a headphone socket, micro-USB and/or micro HDMI, GPS, accelerometers and anything else customers have come to expect.

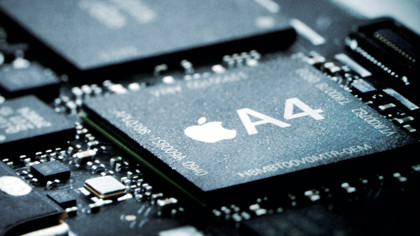

In mobile devices, there simply isn't room for anything that isn't absolutely necessary - and that often means there's no room for Intel chips. With very few exceptions, the smartphones and tablets set to dominate 2011 aren't powered by Core processors or Atom ones; they're running Qualcomm's Snapdragon, Nvidia's Tegra 2 or Apple's A4.

Such processors aren't just processors - they're graphics cards and wireless radios too. The industry calls them SOCs - systems on a chip.

SOC it to 'em

A typical SOC contains almost everything you need to build a mobile device. The Snapdragon SOC in the forthcoming Asus Eee Pad Memo has dual 1.2GHz processor cores, 1080p HD video encoding and decoding, integrated GPS, integrated wireless (both Wi-Fi and mobile) and integrated audio. It also supports external displays of up to 1,280 x 800 resolution.

The SOC comes from Qualcomm, but the underlying architecture comes from elsewhere: the SOC is based on ARM's Cortex A8, which also underpins Apple's A4 SOC. Nvidia's Tegra 2 is based on the same firm's newer A9.

Where Intel's model is based on designing, fabricating and selling a range of processors in a kind of catalogue model - "here's what we've made. Which one would you like?" - the SOC model is different: ARM designs the technology and licenses it, and it's then up to the licensees to adapt the technology to suit their own requirements and find a suitable company to manufacture the resulting designs.

That model means that the same core technology can be used to create a range of different SOCs - Snapdragons, Tegras, A4s and so on - designed for very specific mobile applications and built in much smaller quantities than, say, an Intel Atom variant.

For example, to create its A4 SOC, Apple took ARM's Cortex A8 and worked with Samsung to improve its performance. The result, dubbed 'Hummingbird', is exclusive to Apple, and comes in multiple configurations - the version used in the iPad, iPod and Apple TV has 256MB of SDRAM, but the version in the iPhone 4 has 512MB.

No Intel inside?

ARM co-founder Hermann Hauser thinks the SOC model leaves precious little room for Intel. Speaking to the Wall Street Journal, he claimed:

"Intel has the wrong business model... People in the mobile phone architecture don't buy microprocessors, so if you sell microprocessors, you have the wrong model. They license them... it's not Intel versus ARM, it's Intel versus every single semiconductor company in the world."

As former Nokia manager Horace Dediu wrote on asymco: "In the world of mobile computing, it's the device itself that isn't yet good enough and you can't back off from pushing all the components to conform to your device's purpose. For a device to be competitive, it has to be optimised with a proprietary, interdependent architecture... Intel's integrated business model is obsolete in a device world. No amount of polishing of the Atom will help."

Intel isn't taking such claims lying down. As head of Intel's PC client group Mooly Eden told us, "We're serious about this category. We're designing great low power in microprocessors. It will be much more meaningful in 2012, [and] another category we're dead serious about is smartphones."

Intel has two processor families: Sandy Bridge, the next iteration of the Core processor family, and Oak Trail, the latest Atom processors, and we'll see tablet PCs based on both technologies in 2011: for example, Acer will release twin Sandy Bridge-based tablets later this year.

It's clear, however, that Intel sees the mobile future as a case of business as usual: according to Eden, the tablet hype will die down. "I believe in the future, the hype will be over and it will be just another category complementing [the PC]," he says.

"At the moment, it's the new kid on the block." Microsoft, it seems, doesn't share Intel's confidence: in January, it announced that the next version of Windows would also be available for ARM-based processors.

- 1

- 2

Current page: How smartphones and tablets are taking over

Next Page The unstoppable rise of apps