Beyond Webb: why NASA's new $10 billion space telescope is just the beginning

Here are the next-gen telescopes planned in the years ahead

We need more light.

Having launched on Christmas Day, the James Webb Space Telescope is now at its destination and preparing to make some incredible observations, but the race to build the next big ‘eye on the sky’ is never-ending.

In recent years it’s been space-based telescopes like Hubble, Spitzer and now Webb that have gotten all the headlines, but on the back of new tech there’s about to be a new generation of massive ground-based observatories…and a few more space-based telescopes for good measure.

Here are some of the massive engineering projects astronomers hope will get them ever more detailed images of galaxies, exoplanets, black holes and nebulae.

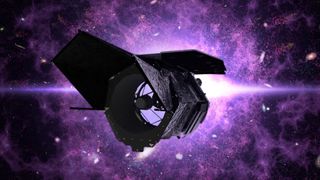

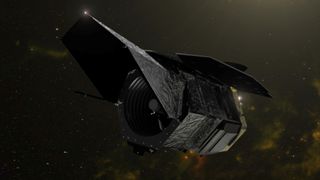

Roman Space Telescope

Where: second Sun-Earth Lagrange point, L2, same as Webb

When: May 2027

Formerly known as the Wide Field InfraRed Survey Telescope (WFIRST) and in the planning for 12 years already, the $3.2 billion Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will be another infrared space telescope – much like Webb – designed to explore dark energy, exoplanets and infrared astrophysics.

It will have a roughly 8-foot/2.4-meter mirror, the same as Hubble, but capture 100 times more of the night sky in its much wider field of view.

Its five year ‘to do’ list includes scanning the galaxy for at least 2,600 exoplanets, directly imaging them using its unique coronagraph (which will eclipse the light of stars), capturing the light from a billion galaxies and helping astronomers understand how the Universe expands.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

Destined to go into orbit at L2–the same place in space as Webb–Roman is named after the ‘mother of Hubble’.

Vera C. Rubin Observatory

Where: Cerro Pachón, Chile

When: 2022

Of all the giant observatories being planned the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is perhaps the most exciting – and it’s about to see ‘first light’.

An roughly 26-foot/8-meter telescope on Cerro Pachón in Chile, it will begin an all-sky astronomical survey in 2022 that could revolutionize astronomy.

It will survey the entire visible sky in just three nights, effectively producing a motion picture of our Universe that will instantly identify any moving object and any minor change in the night sky.

Astronomers are expecting it to find many more objects in the Solar System – chiefly Pluto-like dwarf planets in the outer regions and "Planet 9" if it’s out there – as well as thousands of supernovae.

Rubin will also find 90% of near-Earth objects – asteroids – larger than 300 meters, then calculate if they are a threat to Earth.

Equipped with a 21-foot/6.5-meter mirror and a 3.2-gigapixel CCD imaging camera, it’s expected to take 1,000 images each night, totaling 15TB of data. It was built next to the Gemini South telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile.

Extremely Large Telescope

Where: Cerro Armazones, Chile

When: 2027

Astronomers are excited about the size of Webb’s mirror – 21-feet/6.5 meters to Hubble’s 8-feett/2.4 meters – but the next generation of ground-based telescopes are going to be bigger. Much bigger.

The biggest of all currently in the planning is the (not very imaginatively-named) Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) now being built by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) on top of Cerro Armazones in Chile at a dizzying 128 feet/39 meters.

Destined to be the largest optical telescope in the world for many decades, the ELT will have a resolution a whopping 16 times that of Hubble.

Its laser-powered adaptive optics technology, which will correct for the distorting effect of Earth’s atmosphere, is its secret sauce – and explains why ground-based telescopes are back in fashion. The ELT is expected to be just as ground-breaking for astronomy as Webb, if not not more so.

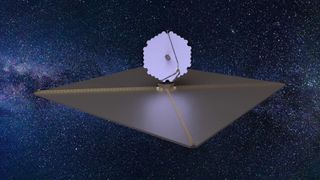

LUVOIR-HABEX

Where: second Sun-Earth Lagrange point, L2, same as Webb

When: 2040s

A space telescope capable of photographing potentially habitable worlds – perhaps an Earth 2.0 – could soon be on the cusp of development.

Just recommended as a top priority for the U.S. by the National Academies’ recent decadal survey, this next new flagship space telescope after Webb will likely be a space telescope with at least a 20-foot/6-meter mirror.

Destined to be a compromise of two existing and very ambitious concepts – the huge 15-meter, $17 billion LUVOIR and the 4-meter, $10.5 billion HabEx – its core mission will be to detect and characterize Earth-like planets orbiting other stars.

The compromise can be summed-up this way; spending many billions of dollars on LUVOIR in an attempt to find 1,000 Earth-like planets is probably overkill, but HabEx might find only one or two, so it is too risky.

So the plan is to go for something in between.

Giant Magellan Telescope

Where: Cerro Las Campanas, Chile

When: 2029

Things are looking good for the Giant Magellan Telescope, an optical and infrared telescope being planned for Las Campanas Observatory, Atacama. Chile.

In 2021 it – together with the controversial Thirty Meter Telescope (whose future is currently in the balance) – were ranked as a top strategic priority for the U.S. by the decadal survey.

The GMT will have seven 28-foot/8.5-meter diameter mirrors to create a massive 83.3-foot/25.4-meter aperture telescope. It will also have adaptive optics, and its images will be 10 times sharper than Hubble’s in the infrared.

Like many big telescopes it’s going to study the southern hemisphere night sky from Chile’s Atacama Desert, one of the best locations on Earth for astronomy due to its high altitude and low levels of light pollution.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),

Most Popular