WikiLeaks' latest leak reveals alleged CIA exploits for Mac and iPhone [Updated]

More CIA spying tools come to light

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Update: Apple has sent us a statement regarding the latest WikiLeaks revelations. The company says its initial assessments show the alleged iPhone vulnerabilities described only affected the iPhone 3G and were fixed when the iPhone 3GS was launched in 2009.

As for the Mac exploits, Apple says these also appear to have been patched in all Macs released after 2013.

Apple's statement is in full below:

"We have preliminarily assessed the Wikileaks disclosures from this morning. Based on our initial analysis, the alleged iPhone vulnerability affected iPhone 3G only and was fixed in 2009 when iPhone 3GS was released. Additionally, our preliminary assessment shows the alleged Mac vulnerabilities were previously fixed in all Macs launched after 2013.

We have not negotiated with Wikileaks for any information. We have given them instructions to submit any information they wish through our normal process under our standard terms. Thus far, we have not received any information from them that isn’t in the public domain. We are tireless defenders of our users' security and privacy, but we do not condone theft or coordinate with those that threaten to harm our users."

Original story...

WikiLeaks has released a new set of documents related to alleged CIA spying techniques, this time detailing tools purportedly used by the agency to gain access to Apple Mac computers and iPhones. It's calling this new leak Dark Matter.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The majority of today's document dump, part of the organization's larger Vault 7 leak, deals with ways the CIA could exploit Macs. It's unclear if these tools are still in use today or would be as effective on newer machines, though Apple has patched at least one of the vulnerabilities detailed.

The first exploit is called Sonic Screwdriver, and it let the CIA execute code from a peripheral device onto a laptop or desktop while the machine was booting. The code would be carried on an Thunderbolt-to-Ethernet adapter and would execute when the target Mac powered on.

Apple recognized the potential for third-party devices to do this and patched the hole in 2015, as TechCrunch points out.

Then there's Triton, an automated implant for Mac OS that can access computer files once installed on a hard drive. The CIA would allegedly alert the malware to start sending files – referred to as "payload" in the documents – a directive the agency could carry out at any time.

Related to Triton is Der Starke, a diskless version of the Triton malware that would go undetected on a hard drive. It could send data via a browser process, allowing it to fly under the radar of network monitoring systems.

Three other Mac-related tools – Dark Matter, SeaPea and NightSkies – fall under a blanket term called DarkSeaSkies. Working together, these exploits operated similarly to Der Starke to stealthily retrieve data from computers.

iPhone exploit

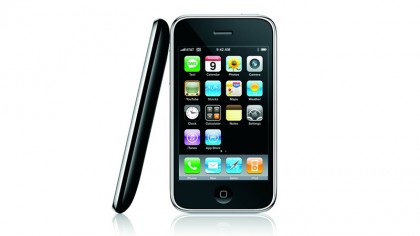

Last but not least is NightSkies, described as a beacon/loader/implant tool for the iPhone 3G.

Once the CIA installed it on a phone (it would have to be done physically), the agency could track things like browser history, YouTube videos, map files and the meta data for emails.

The exploit could nab files such as the address book, SMS and call logs, execute commands on the iPhone, take full remote control of the device and upgrade itself. NightSkies would run in the background of the exploited iPhone.

While all of these tools are relatively old, having the most up-to-date version of iOS and Mac OS X will provide you with the most recent security patches and therefore the best chance at keeping your devices secure.

For more on WikiLeaks' Vault 7 leaks, check out our comprehensive guide.

Michelle was previously a news editor at TechRadar, leading consumer tech news and reviews. Michelle is now a Content Strategist at Facebook. A versatile, highly effective content writer and skilled editor with a keen eye for detail, Michelle is a collaborative problem solver and covered everything from smartwatches and microprocessors to VR and self-driving cars.