So-called ‘gaming Chromebooks’ are a con – here’s why

Chrome OS could be the new frontier for gaming… or not

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Google’s latest move to keep Chromebooks relevant in the face of Apple’s growing share of the laptop market is to work with manufacturers to produce ‘gaming Chromebooks’. Acer, Asus, and Lenovo have all pitched in with their own new models. I’m not impressed, though – in fact, I’m distinctly unimpressed with this whole affair.

These new Chromebooks certainly look and sound the part as far as gaming hardware's concerned. Dark color schemes, RGB LEDs beneath the keycaps, and high-refresh-rate displays are all things we’d expect to see in any Windows-powered thin and light gaming laptop.

The bottom line is this, though: even the best Chromebooks aren’t really capable of running the latest games on their local hardware. Chromebooks don’t have dedicated graphics cards like most gaming laptops do, instead relying on integrated graphics built into the CPU. Most Chrome-powered laptops use Intel Core or Qualcomm Snapdragon processors, with some cheaper models using MediaTek chips.

So can you really game on a Chromebook?

While integrated graphics have come a long way in recent years, Chromebooks aren’t built with gaming in mind; they’re generally cheaper and lighter than Windows laptops, with less powerful processors and smaller drives to allow for a focus on cloud computing and better battery life. The Chrome OS operating system also isn’t well-suited for playing games since it can’t run Windows software – most PC games require a third-party platform like Steam or Epic to launch and run, which aren’t currently supported on Chrome OS (although proper Steam compatibility is in the works).

Chrome OS has, however, integrated the Google Play Store – the same one you’ll find on most Android phones – so you can download a ton of app games designed to run on lower-powered hardware. This means you can technically play stuff like Fortnite and Pokemon Unite on a Chromebook and get reasonable performance since these versions of the games are built for mobile devices.

The thing is, you don’t need a ‘gaming Chromebook’ to do this. Almost any modern Chromebook can handle games meant to be played on a phone, after all. In fact, many games on the Play Store could feasibly run on a tub of strawberry ice cream. But these new gaming Chromebooks claim to offer ‘powerful PC gaming’ with featured titles, including Destiny 2, Cyberpunk 2077, and the totally kickass Deathloop, my favorite game of 2021. How? Simple: cloud gaming.

Head in the clouds

For the uninitiated, ‘cloud gaming’ refers to a process where games aren’t run on your computer’s local hardware, but streamed from ‘the cloud’ – that nebulous term for computer systems and servers that can be accessed remotely via an internet connection. In this case, your games are streamed from a gaming-focused cloud setup equipped with powerful graphical capabilities, so the only limit – in theory – is the speed of your internet connection.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Now, I’ve never been particularly invested in the future of cloud gaming for a wide variety of reasons. Anyone who followed my work back in my heyday at Maximum PC magazine will have already bore witness to my whining about Stadia, Google’s own cloud gaming platform. Just a few months ago, the tech giant announced Stadia would be shutting down completely, which makes this new push for cloud-gaming-focused Chromebooks all the more baffling to me.

To put it lightly, cloud gaming has had a troubled history. Stadia, supposedly the poster boy for modern cloud gaming, went the way of the dodo. The original progenitor of the technology, OnLive, burned bright and then promptly burned out after being acquired by Sony back in 2015. Luna, Amazon’s attempt to breach the cloud gaming sphere, is still up and running but with a feeble user count numbering in the thousands.

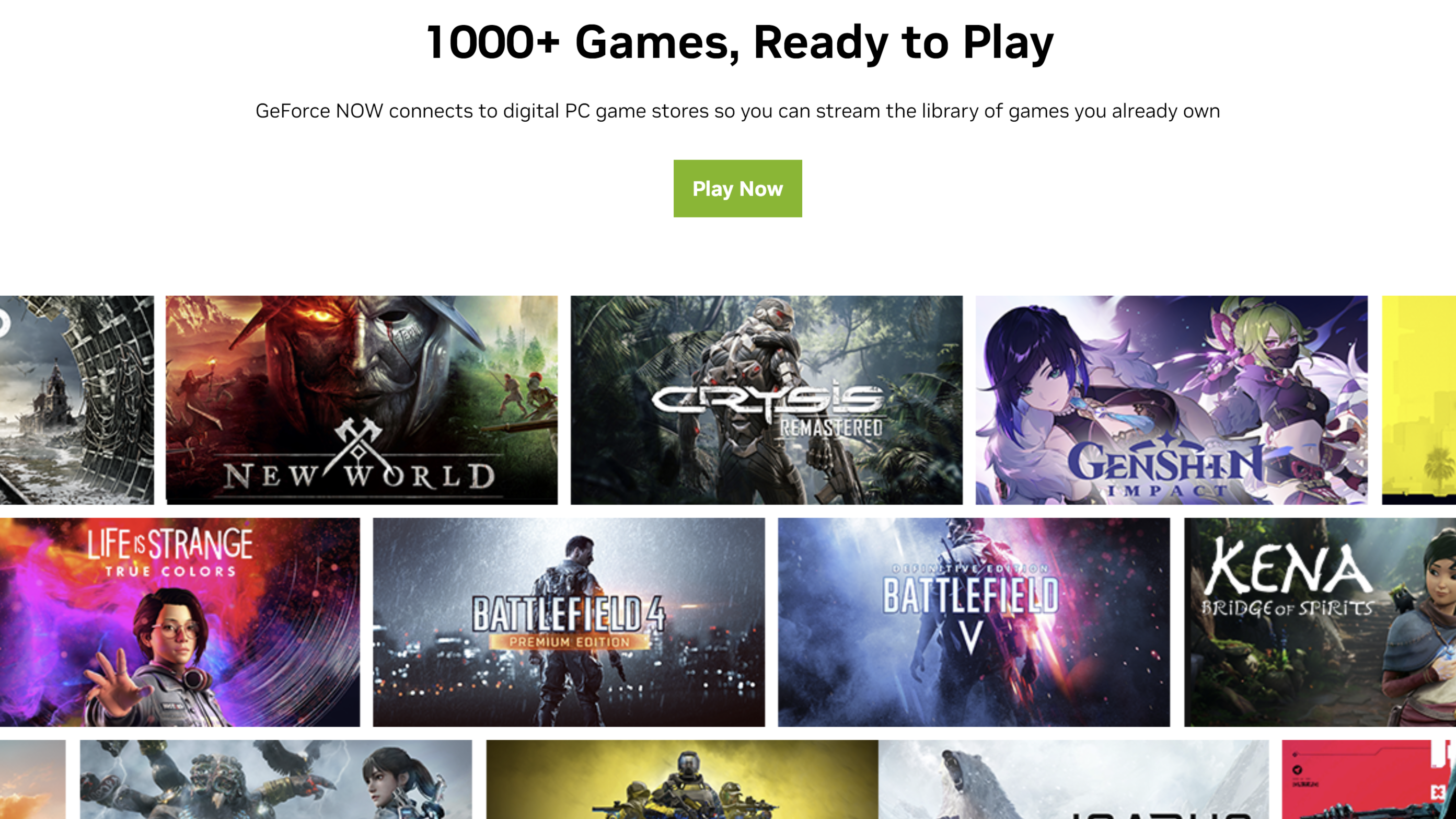

The two platforms that have managed to gain a significant following are Nvidia’s GeForce NOW service and Xbox Game Pass. The latter is actually just a conventional games-on-demand subscription, but cloud play for select games is currently available in open beta. GeForce NOW is the dominant force when it comes to cloud-based gaming, which I’m oddly heartened to see. This service has actually been kicking around for a lot longer than Stadia or Luna, but it exploded in popularity over the past two years, rising from 1 million to 20 million registered users.

Crunching the numbers

So, 20 million users sounds like an awful lot, doesn’t it? Let’s put that figure into perspective real quick. For starters, that’s the total number of GeForce NOW accounts, not the number of regular active users. For comparison, Steam – which requires local hardware to play games – had more than a billion accounts according to a 2019 report by Tom’s Hardware (thanks, guys).

In 2022, the number of active Steam accounts sits at more than 120 million, with more than 62 million logging into the service on a daily basis. PlayStation Network has approximately 103 million monthly users as of September 2022. Beyond individual platforms, Statista puts the total count of ‘gamers’ at a whopping 3.03 billion, almost half of the global population. If I do some quick maths right here, that means that about 0.67% of the world’s gamers are using GeForce NOW to play their favorite games.

Let’s take a slightly more generous interpretation, though, since Statista’s definition of ‘gamer’ includes your weird aunt who keeps spamming you with invites to join her gem-smashing smartphone game. Getting a bit more focused down to ‘PC gamers’ gives us a total figure of… oh, it’s still 1.75 billion according to a 2020 study, and probably more by now. Can we get an F in the chat for cloud gaming?

Fantastic problems and how to fix them

See, the problems that caused cloud gaming platforms like OnLive and Stadia to crash and burn haven’t gone away. I’ll tackle the biggest issue first: internet speed. Google recommends a speed of 15Mbps as a bare minimum, with 35Mbps recommended – and an ethernet connection strongly advised for optimal performance. Obviously, you can’t play jack if you don’t have an active internet connection.

I’m gonna say it right now from my experience with multiple cloud gaming services: these are some pretty damn conservative recommendations. I tried using GeForce NOW earlier this year on my 20Mbps rural internet and it was a painful experience. If you’ve never played a locally-installed game in your life, then you might not notice a difference, but to a lifelong PC gamer like myself, the latency was small but there, and it was enough to make me want to rip my hair out.

When I tried using the same service (along with European cloud computing service Shadow) on a higher-speed 80Mbps fiber connection, things were a lot more palatable. Unfortunately, not everyone has the luxury of speedy internet; according to FastMetrics, the United States sat at number thirteen on the global ranking of internet speeds in 2020, with an average download rate of 54.99Mbps and upload of 10.45Mbps.

Unlike downloading games to play locally, upload speed is very important for cloud gaming since that’s how the cloud server running your game receives your controller inputs. High download speed but low upload speed means you’ll have a nice, smooth framerate, but input lag will result in your actions registering a split second after you hit a button or tilt an analog stick – a death sentence in many a fast-paced game.

The urban vs rural distribution of internet infrastructure in the US means that unless you live in a major metropolitan area, you probably won’t have fast enough internet to use a gaming Chromebook for its intended cloud-based purpose. And that’s just the US. Out of 192 countries included in FastMetrics’ list, only 48 had an average download speed of 15Mbps or above – Google’s recommended minimum for cloud gaming. It's not just small developing nations with this problem; Italy, France, India, and China all fall far below the advised speeds.

Network infrastructure has always been a big obstacle to cloud gaming (and cloud computing in general), and was cited as a major reason behind the failure of OnLive. Ironically, the one propagator of cloud gaming who could actually do something about this – Google, of course – has struggled for years with expanding its own fiber broadband service.

If at first you don’t succeed, pay, pay again…

This brings us to the second big issue with cloud gaming: cost. Sure, not everyone can afford an Nvidia RTX 4090 for their PC, but gaming-capable hardware is a lot cheaper than it used to be – our favorite cheap gaming laptops are leaps and bounds ahead of what was available a decade ago when it comes to performance.

Cloud gaming services like GeForce NOW and Amazon Luna require a monthly subscription, and while you can use them on a bog-standard laptop, you’re also going to have to pay for a high-speed internet connection. Many such platforms also require you to own the games you want to play, too, so you’ll need to shell out for those too – this is where Game Pass has a big advantage with its huge library of games as standard.

Of course, if you’re paying for games-on-demand you don’t actually own any of those games and you’ll lose access to them if you stop paying the monthly fee, something that doesn’t sit right with me. Yes, I’m aware that my massive Steam library could go kaput if Valve ever collapses, but that’s a different kettle of fish. In practical terms, when I buy a game on Steam or GoG, that game is mine to play whenever I choose to with no further payments necessary.

This is the sting in the tail of gaming Chromebooks: they’re already more expensive than most regular Chromebooks – which, to reiterate, can make use of the exact same cloud gaming services – and you’ll have to pay a regular fee if you want to play games on them, plus the cost of the games themselves if you’re not opting for Game Pass. I’m not having any of this nonsense.

The Chromebook conundrum

My fear is that well-intentioned but ill-informed parents will buy these new Chromebooks for their game-crazy kids without understanding the ramifications. GeForce NOW costs $10 a month, and the cheapest of Google’s new gaming machines – the Lenovo IdeaPad Gaming Chromebook 16 – costs $400. That means that gaming for two years on such a laptop will cost you $640 – around the same price as a proper budget gaming laptop like the lower-spec Acer Nitro or Asus TUF models.

To be perfectly honest, the prices of all these gaming laptops are rather inflated. At $400, a Chromebook with an i3 processor is a smidge on the pricey side, but the offering from Asus runs up to $730 for a very midrange Intel Core i5 CPU. It took me about 10 seconds of Amazon searching to find a similar i5-powered Chromebook for $580. Paying a hundred and fifty bucks extra for a better display refresh rate and a rainbow-lit keyboard just sucks, man.

Beyond this, if you’re looking for a laptop to do schoolwork with the occasional bit of low-intensity gaming, the processor-integrated graphics found in many conventional non-gaming notebooks and Ultrabooks are improving at an incredible rate. You can run less demanding titles like Fortnite and Valorant on whatever cruddy potato-spec computer you have to hand.

I’m sure these gaming Chromebooks will be perfectly fine pieces of hardware. I’m actually quite excited to get my hands on one and test it out myself – Google makes the point on its website that they should be great for general workloads outside of gaming, after all. Really, it’s the notion of a ‘gaming Chromebook’ that I object to. If you’re using cloud-based systems to achieve that goal, surely every Chromebook is a gaming Chromebook? My Google Pixel 5 could access Stadia to play games, but that doesn’t make it a gaming phone.

In short, cloud gaming isn’t the ‘future of gaming’ – at least, not yet. Once high-speed internet is widely available – perhaps when someone other than ol’ Musky gets a proper satellite internet service up and running – then maybe it’ll truly take off. But the world wasn’t ready for OnLive, it wasn’t ready for Stadia, and it’s definitely not ready for cloud-gaming Chromebooks. Until it is… don’t buy one.

Christian is TechRadar’s UK-based Computing Editor. He came to us from Maximum PC magazine, where he fell in love with computer hardware and building PCs. He was a regular fixture amongst our freelance review team before making the jump to TechRadar, and can usually be found drooling over the latest high-end graphics card or gaming laptop before looking at his bank account balance and crying.

Christian is a keen campaigner for LGBTQ+ rights and the owner of a charming rescue dog named Lucy, having adopted her after he beat cancer in 2021. She keeps him fit and healthy through a combination of face-licking and long walks, and only occasionally barks at him to demand treats when he’s trying to work from home.