Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The ARM architecture started out in a desktop PC, and a powerful one at that. Now, after years of being hidden away in a whole manner of consumer and industrial products, it has returned to the world of computing by powering the latest generation of portable platforms. So will ARM products once again power mainstream computers?

I put that question to Ed Plowman, who questioned our use of the term 'mainstream' and turned the question on its head by referring to the evolution of computing devices.

"First there was the desktop, and then the laptop, but the laptop was hindered by the lack of connectivity", he said. "All of this functionality plus connectivity can now be provided in a device that's always with us, but there's a limit to what you can do with a smartphone, which is why the tablet was developed. It would be wrong to think of a tablet as just a bigger phone, though; it provides a different way of presenting data and a different user experience. So ARM isn't moving into the mainstream but the mainstream is evolving to play into ARM's strengths such as low power consumption".

However we might define the mainstream, there seems to be little doubt that ARM devices are being called on to perform ever more processor-intensive tasks. The fact that this has been achieved with a 32-bit architecture when most of the competition at the top end has migrated to 64 bits is a testimony to the ARM architecture, but surely there's a limit to how far 32-bit technology can be stretched.

At ARM's TechCon conference in Santa Barbara in October last year, Ed mentioned the company's forthcoming ARMv8 architecture, which will be 64-bit throughout. He wasn't prepared to say when 64-bit designs will become available, but Ed was enthusiastic about what it will offer.

"Availability of a 64-bit ARM core takes us into interesting areas. People think it's predominantly about taking us into an Intel-type world, but there are lots of other advantages, not least of which is the scope for vastly increasing use of memory."

Indeed, coping with huge volumes of data brings us to another new application for ARM devices as evidenced by the recent announcement by HP of the Redstone server. This new product line uses ARM Cortex-based processors produced by start-up company Calxeda.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

However, Ed Plowman took issue with the suggestion that ARM's entry into the large scale server market was a radical change of direction. "People think that servers are all about high performance, but most applications are data centres where the main requirement is energy efficiency", he said.

"Electrical power is needed both to run the hardware and for cooling, and this cost overrides the equipment cost. With the continual requirement for larger and larger data centres, the number of MIPS per unit area and power efficiency are becoming increasingly important".

It's interesting to note, therefore, that an aim of HP's Project Moonshot, of which the ARM-based Redstone server is a first element, is to consume 89 per cent less energy and 94 per cent less space, while reducing overall costs up to 63 per cent compared to traditional server systems.

ARM might be best known for its microprocessors and cores, but GPUs are becoming an increasingly important part of their portfolio with their newly announced Mali-T658 representing the state of the art. Needless to say, this new product follows in the ARM niche of low power consumption for handheld and portable devices, without sacrificing performance.

Indeed, a recent press release refers to desktop-class graphics on mobile devices, and Ed went on to make the tantalising suggestion that it would allow mobile phones to be driven via a gesture interface.

Whether we'll ever see a desktop PC proudly displaying an 'ARM Inside' badge remains to be seen, and unless it does the company will probably never become a household name. Yet ARM Holdings appears in the FTSE 100 list of the UK's most influential companies, employs 1,700 people, turns over more than £400 million, and demonstrates that a British company can compete with the best that Silicon Valley has to offer.

With pundits continually talking down the British economy, perhaps you'll forgive us relishing in this success story for the British computer industry.

Learn to program ARM chips

Get to grips with the mbed rapid prototyping platform

Given that ARM can trace its ancestry back to the educational market, it's perhaps appropriate that the company has launched an initiative that represents a return to its roots.

In those early days of the BBC Micro, if you wanted to do something useful with the hardware, it often meant rolling up your sleeves and creating some BASIC code. In an attempt to get people programming again, ARM has launched the mbed rapid prototyping platform, which simplifies the process of developing code for ARM processors.

The name mbed comes from the concept of an embedded application, the name given to an application that runs in the background, perhaps in something like a microwave or a washing machine, often completely unbeknown to the user.

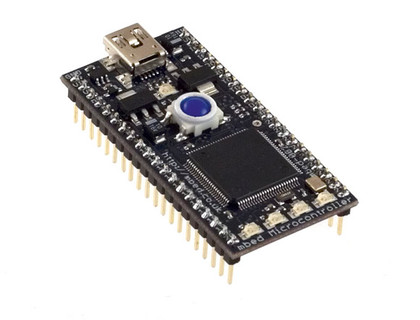

Although you'd have to buy a development board - a small circuit board containing an ARM processor and the necessary circuitry to interface it to external hardware and costing from around £35 - the associated C/C++ compiler is freely available at http://mbed.org.

You can find all the necessary project documentation on the mbed website, along with a large collection of ARM code, contributed by other mbed users, that you are free to adapt for use in your own software.

If you're still to be convinced that mbed is for you, you might be interested to know that an ARM-powered robot arm has solved the world speed record for solving the Rubik's Cube, and other exciting amateur projects have involved racing robots around a track and controlling a remote weather station.

Spotlight on the Archimedes

How the BBC Micro's successor changed the face of computing

The Archimedes was never as well known as its hugely successful predecessor, the BBC Micro. Yet without it, the ARM architecture would probably never have come into being and today's smartphones and tablets might boast Intel rather than ARM technology.

So what was so special about this personal computer that it changed the face of the micro electronics industry? At first sight, the specification doesn't sound particularly special.

The entry-level model 305 had an 8MHz processor, 512KB of memory and a single floppy disk drive (a hard disk was an optional extra), and it cost £899. However, in comparison to most home computers of the day, which were little more than toys, cassette tape data storage and all, the Archimedes was much closer we'd think of as a proper PC.

Of course the IBM PC and the Apple Mac were already available, and while these were undoubtedly serious computers, they had price tags that, back in 1987, meant that they were first and foremost business tools and rarely found their way into the home.

What made the Archimedes stand out from anything else at the time with a similar price tag was its graphics. With a resolution of 640 x 256 (or 640 x 512 with the optional high resolution monitor) in 256 colours, the Archimedes stood head and shoulders above the competition.

Even the IBM PC could only boast 640 x 200 pixels in monochrome or 320 x 200 in four colours. And while Windows wouldn't become popular on the PC for another five years with the launch of Windows 3.0, at the outset the Archimedes could boast a graphical user interface.

This brings us back to that innovative 32-bit RISC ARM chip, without which the Archimedes' high resolution graphics and GUI just wouldn't have been feasible.