The masters of sci-fi: How one nation took us to space and beyond

If you love space, aliens and future-gazing, you probably owe it to the French masters of science fiction

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Space tourism, Hyperloops, AI voice activated smart speakers and driverless cars – the current rate of technological progress and exploration can make the present seem like the sort of sci-fi future that we once only dreamed of. But as these dreams become reality, it’s increasingly obvious that science fiction has become the chalkboard for tomorrow’s inspirational technologies. But what of science fiction itself? Where do we find the roots of its family tree? The speculative, future-gazing works of one nation arguably now stand above all others as the greatest font of inspiration.

The most important thing is what you’re saying. It’s not so much what is the tool you’re using to say it, I’m more concerned about what we are saying. Is it a good story? Is it a good film? Then it doesn’t matter if you see it on a small screen or a big screen.

You have some big films coming from books, and you have people who’ve never read the books, they have seen just the film. That’s OK! It’s still the same story, if the story is good it’s good. No one is complaining, asking 'why didn’t you read the book?' It’s OK, you can read the book or watch the film or do both. A story is a story, and the storytelling will be always the master of the thing for me.

The moment Georges Méliès rocket crashed into the eyeball of our nearest celestial neighbour in 1902’s A Trip to the Moon could have been seen as a French national flag planting ceremony in the new found land of sci-fi cinema. For more than a hundred years the nation’s artists and directors have taken us on fantastic voyages through space and time, from Méliès moon to this summer’s blockbuster Valerian by Luc Besson, whose subtitle promises to show us “The City of a Thousand Planets.”

Literary launch

It’s a tradition however that was rooted first firmly in literature. Jules Verne’s 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon, the inspiration for Méliès’ seminal silent movie, sees the master of adventure conjure an American trip to the moon a century before NASA managed the journey for real.

Though its concept of firing men to the moon in a giant cannon seems disastrously dangerous today in the age of SpaceX and Blue Origin Verne’s calculations elsewhere are surprisingly prescient – right down to the cannon’s construction site being imagined close to where the real-world Kennedy Space Center now exists.

Verne would dabble in science fiction regularly throughout his working life. Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, first published in 1870 brought us the impossibly cool Nautilus submarine, pretty much single-handedly inventing steam punk and given a liberal tip of the hat by Besson in Valerian’s spectacular underwater scene. It’s an aesthetic that’s been heavily mined in games like Dishonored 2, and has informed a modding scene looking to add some historical, brass-flourished glamour to the current tech world. Verne’s 1874 novel Journey to the Center of the Earth could even be seen as a proto-Jurassic Park, with its character encountering prehistoric wonders such as the Mastodon and Pterosaurs.

Though Verne is the best known today, he inspired sci-fi contemporaries including Maurice Renard and Charles Derennes (whose pulpy 1907 The People of the Pole, with its tech-savvy reptilian civilisation, is ripe for a ‘re-imagining’) among countless others around the globe.

The French literary sci-fi well dried up a bit in the middle of the 20th century. It wasn’t, however, completely spent before Pierre Boulle delivered his 1963 novel Planet of the Apes, that most-oft revisited of speculative worlds, itself enjoying a silver-screen renaissance this summer with War for the Planet of the Apes, the concluding part to the CGI, motion-capture-heavy, Andy Serkis-led reboot trilogy.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Comicbook comeback

But one area in which the sci-fi page-turners again began to flourish, and were to become more inspirational than ever before, was in the blossoming pages of the comic book.

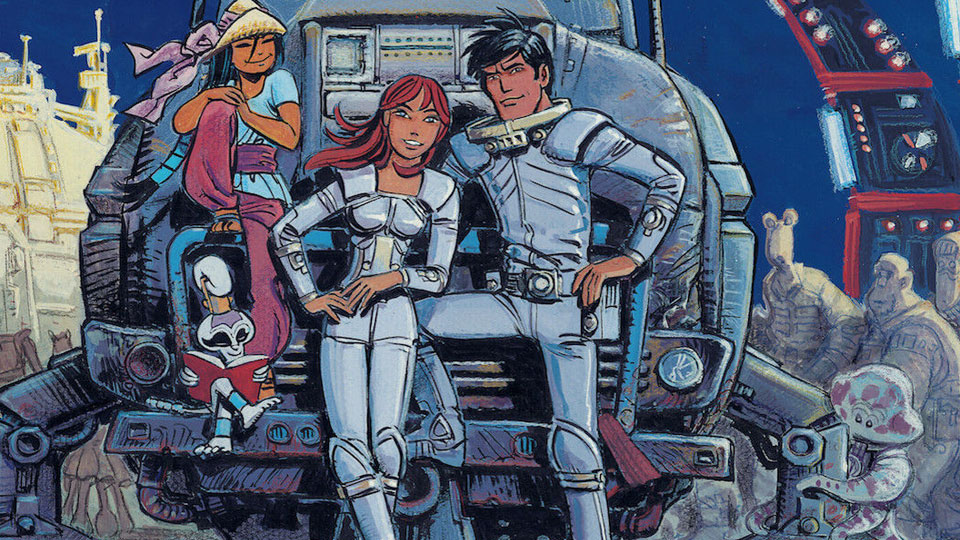

Leading the charge were writer Pierre Christin and artist Jean-Claude Mézières. Their comic Valérian and Laureline, first published in Pilote magazine in 1967 had it all – a menagerie of alien races, luminescent planets, time travelling special agents and a healthy dollop of sex appeal.

“My first introduction to science fiction was Valérian and Laureline”, says director Luc Besson, taking the reins on this year’s cinematic adaptation of the strip.

“I was ten years old. Every Wednesday there was a magazine called Pilote in France, and there was two pages of Valerian every week. It was the first time I’d seen a girl and a guy in space, agents travelling in time and space. That was amazing.”

The ‘lived-in’ look of the Star Wars films can be traced back to Valérian and Laureline’s functional-but-fantastic approach to design, while the liberally-minded, socially-progressive way that each alien race had more or less a level footing in the eyes of Valérian’s world can be seen replicated in the Mass Effect videogame series.

Whether the Mass Effect team at Bioware were actively fans or guided towards this view of intergalactic equality through Valérian and Laureline’s copycats across the decades is unknown, but in the case of Star Wars, the similarities are too many to be mere coincidence; clone armies, bloated crime lords on floating barges, metal bikinis, carbonite-like restraining methods and a penchant for single-biome planet-hopping – all escapades that graced the pages of Valérian and Laureline before Skywalker ever got off his moisture farm. Indeed Doug Chiang, design lead for The Phantom Menace, is said to always keep a few Valérian and Laureline volumes to hand.

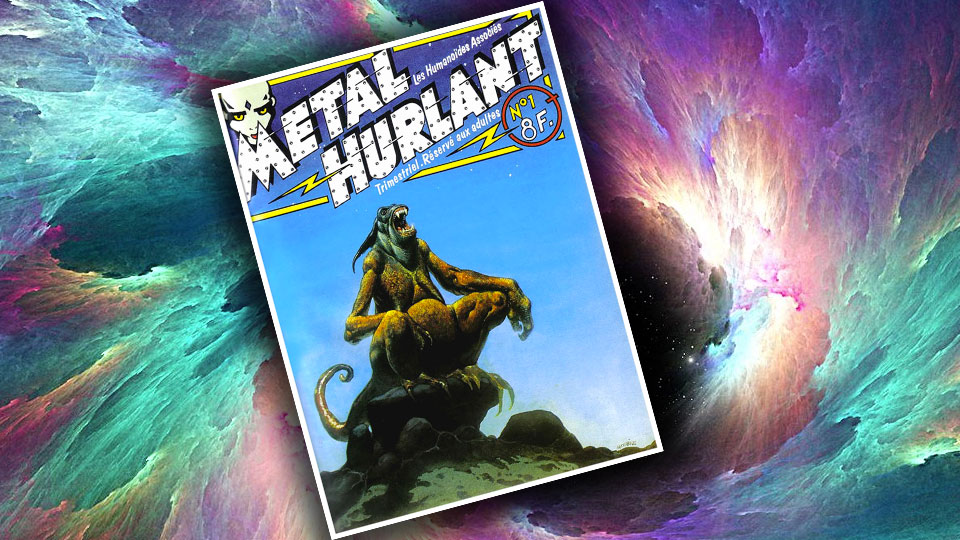

Valérian and Laureline wasn’t the only place for Francophiles to get their sci-fi fixes from though. There was perhaps no book more influential than sci-fi magazine Métal Hurlant.

Published as 'Heavy Metal' in English-speaking corners of the world, it was created in collaboration by comic artists Jean Giraud (aka the inimitable ‘Moebius’) and Philippe Druillet, writer Jean-Pierre Dionnet and money man Bernard Farkas. It’d propel its creators to cult-superstardom and offer a platform to some of the most creative sci-fi minds in Europe, from Enki Bilal to Alejandro Jodorowsky (whose failed attempt to bring Frank Herbert’s Dune to cinematic life is so legendary as to have inspired a fascinating documentary of its own).

“It was a really great time for creativity,” reminisces Besson.

“In fact my first job was selling a script to Heavy Metal – I was in it, it was four pages and I was so proud.

“All these guys, Mézières, Christin, Bilal, Moebius, Druillet, in the 70s they were insane. I don’t know what they were smoking (I’ve never smoked in my life), but they were very free. They were exposing society and showing other things. It was very full.”

Moebius the master

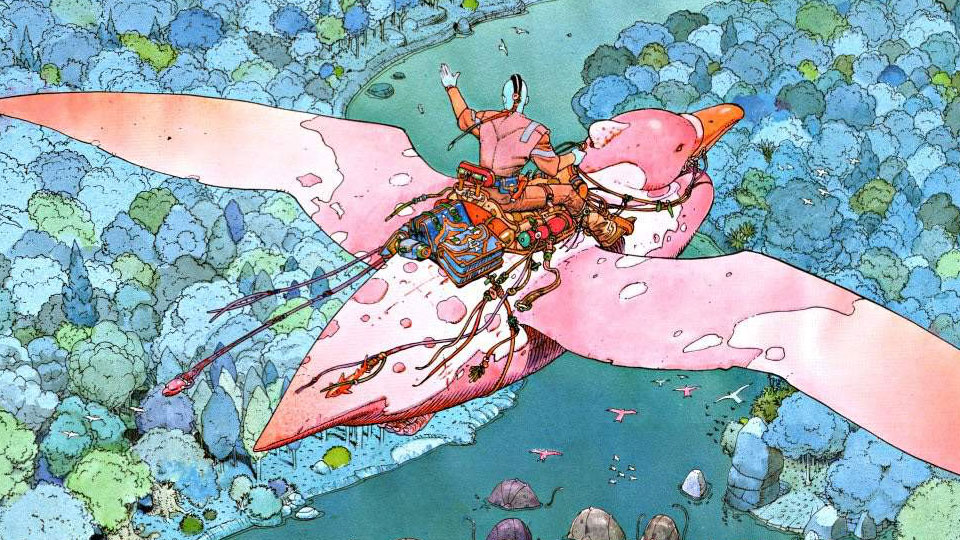

If you’ve enjoyed science fiction in any medium over the past 40-odd years, either the direct work of or at least the spirit of Moebius can be seen running through it. From Studio Ghibli’s Hayao Miyazaki to Neuromancer author and VR-visionary William Gibson, many have admitted a love of Jean Giraud’s stories and art.

From his shorts in Métal Hurlant to longer works like Arzach and The Incal (a collaboration with Jodorowsky), Moebius’s striking use of color, intricate detail and sheer creativity in conjuring out-of-this world concepts made him an unparalleled force. His tenure as steward of Marvel’s Silver Surfer character in the 1988 Parable series had a profound effect on the US publisher’s output, especially in its “Cosmic” Marvel books that included Guardians of the Galaxy. Compare the pages of Moebius’s output with the Guardians’ big screen outings, or the recent Doctor Strange adaptation, and you can see that the psychedelic, vibrant and, most importantly fun tone owes the man a debt.

It was Jodorowsky who brought Moebius to the attention of Hollywood in the mid 1970s for his doomed Dune project, with the comicbook artist working alongside the likes of Alien designer H.R Giger and famed spaceship imagineer Chris Foss. While the epic movie would never be made (Jodorowsky was looking at an unbelievable running time of 14 hours with the Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger and Salvador Dali in starring roles), a production “bible” was distributed among studios featuring the collected designs of the artists in an attempt to gain funding. The money never came, but the bible remained at the studios, where Moebius’s, Giger’s and Foss’s designs would be quietly ripped off and reused in films for decades to come.

Moebius’s time in sci-fi film would come though, with Tron, Alien and The Abyss being just a selection of films he’d work on directly before his death in 2012, aged 73 – the out-of-this-world nature of his designs inspiring filmmakers to continually push the technological boundaries of the medium.

Speaking of Moebius’s influence, Blade Runner and Alien director Ridley Scott said in 2010, “You see it everywhere, it runs through so much you can’t get away from it."

The film element

It’s perhaps with 1997’s The Fifth Element where the sci-fi “French connection” is seen in full force. Worked on by Paris-born Luc Besson on and off since he was aged 16, and inspired by his great love of the Valérian and Laureline comics of his youth, the director would pull together a dream team of Mézières and Moebius for production design, while flamboyant French fashion luminary Jean Paul Gaultier handled costumes. It’s a million miles away from the often-dour approach that Besson’s international contemporaries lean on as standard sci-fi fare.

“Everything is dark, it’s raining, the superhero is wondering what he’s going to do. ‘Am I going to save the world? Or not?’”, says Besson.

“God! Let’s have some color! Let’s have some fun! Let’s at least imagine a better world. Maybe we won’t be able to do it, but we have to try, otherwise we’re going to just kill yourself right now. I’m very optimistic from that point of view.”

The result was an extravagant, boisterous and comfortably playful romp across the galaxy – one in which a cameo from trip-hop star Tricky is somehow the least crazy thing about it. From its atmosphere-scraping tower blocks to its flying taxi cabs, its fetishistic dance-culture inspired costumes, two-dozen octave sky blue alien divas and space-cruising hotel ships which have almost certainly made it into a Virgin Galactic wish-list slideshow at some point, it threw more ideas at the screen in five minutes than some films manage in their entire running times – all shot through with the sense of optimism that’s come to characterise much of French sci-fi over the ages. But it was a slow burner, not fully appreciated upon its original release.

“The Fifth Element didn’t work in the US in fact”, recalls Besson.

“Leon either. Almost none of my films in fact, except Lucy, because Lucy was an American film in a way!

“The Fifth Element took almost 15 years to become a classic, and people are referring to it now, which is very funny for me. Why did you not see it in the first place? 15 years ago! So I guess it’s just the way I’m telling stories is just different, same for Valerian. It’s just different. I don’t want to do the same, I just want to do my own painting.”

And so this summer comes, if not full circle back to Verne, but then a three-quarter circle from Valerian’s comic book fathers to cinema’s Luc Besson. The director’s adaptation is a kaleidoscopic recreation of Christin and Mézières books, the result of giving a true fan an estimated $200 million (it’s the most expensive French film ever) to make their dream vision come to life on the big screen.

As with his sci-fi films Lucy and The Fifth Element before it, it leaves nothing on the table, squeezing every color onto its palette and delivering eye-popping aliens of all shapes and sizes. It’s Besson’s biggest and most ambitious work to date (early scenes which sees the formation of a confederation of alien races, and another with a chase through a multi-dimensional street market, visible only through something akin to an AR headset, must be seen to be believed), and yet thoroughly faithful to its source material.

“Maybe it’s our European side, but we’re not too monolithic, we love to mix salt and sugar,” says Besson on the French sci-fi cannon he is now a leading light in.

“I don’t know if there’s a school of French sci-fi, but there’s a real freedom.”

There’s a few scant moments where an uncanny familiarity, a sense of déjà vu enters Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets – a serene Avatar-like alien here, a Stormtrooper-like guard there. And then it dawns on you – the French have been doing all this for years, the film a culmination of 50 years (if not more) of inspiration from across the Channel. The rest of the world has to make the jump to lightspeed just as an effort to keep up.

Gerald is Editor-in-Chief of Shortlist.com. Previously he was the Executive Editor for TechRadar, taking care of the site's home cinema, gaming, smart home, entertainment and audio output. He loves gaming, but don't expect him to play with you unless your console is hooked up to a 4K HDR screen and a 7.1 surround system. Before TechRadar, Gerald was Editor of Gizmodo UK. He was also the EIC of iMore.com, and is the author of 'Get Technology: Upgrade Your Future', published by Aurum Press.