The Universe of Things is coming and it's set to supercharge 3D printing

Industrial evolution

Imagine if every new product could be printed at home, with only the design having any kind of monetary worth. How different would that world be?

We're talking, of course, about 3D printing and what those in the know are beginning to call the Universe of Things.

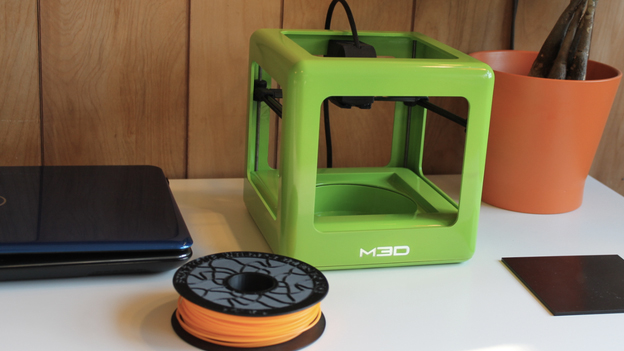

3D printing is currently big news; last week a cut-price consumer 3D printer called Micro passed $2.6 million (About £1.6, AU$2.8 million) on Kickstarter, hitting its goal 50 times over, amid speculation and hope that such machines could even prompt a new industrial age.

It's easy to see why. In the 2D world, knocking-up designs and producing prototypes can take months. But product designers and entrepreneurs now need only a 3D scanner and basic skills in 3D digital modelling – most of it based on existing templates – to do all of that in one day. Meanwhile, worldwide shipments of 3D printers are expected to grow 75% this year, followed by a near doubling of unit shipments in 2015.

It's prompted tech analysts to speak of a Universe of Things, and discuss concepts like open hardware and democratised production.

The theory goes that if we all have our own mini factory at home, we instantly render assembly lines, warehouses and global distribution networks pointless.

Why go shopping, or even have something posted, when you can download the design from the Universe of Things and print it at home? "3D printing is going to spark a third industrial age on a macro level," says Mike Shields, technical director at Centrex Printer Services, "with people printing specialist materials and selling them online to make a profit."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Power of the crowd

"The Universe of Things is the collection of 3D models for everything in the universe, downloadable to print, big or small," says Simon Gill, Executive Creative Director, UK at global marketing and technology agency DigitasLBi.

"It would include the useful, the whimsical, the explorative and the plain stupid... imagine a Wikipedia-like vehicle where you share every object with a creative commons licence for use in ways we haven't even thought of."

"The Universe of Things is the idea that we can fill dark matter with printable or fabricatable objects," thinks Jesse Harrington Au, 3D printing expert at Autodesk. "It utilises the power of the crowd to populate the cloud with substance that can be made into reality."

The Universe of Things also makes transport almost irrelevant; as long as you have a 3D printer and some kind of ink, you can make whatever you want, wherever you want it.

What is the Thingiverse?

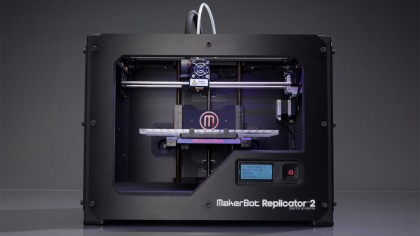

A Universe of Things already exists in the guise of Thingiverse. Created by leading 3D printer-manufacturer Makerbot, Thingverse attempts to simplify how people who have access to 3D printers (all 130,000 of them) can make creative items. Community members upload, download, share and remix 3D designs.

"It's ultimately trying to provide a blueprint for every-object every-where made at every-time," says Kevin Curran, senior member at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and Reader in Computer Science at the University of Ulster.

He thinks 3D printing is about more than just improved designs and streamlined prototyping.

"We can expect to see more serious uses of 3D printing in many areas including food printing," says Curran.

Assembly lines at home

Could we one day have our own factories at home? "Yes – and we will start shipping bits instead of atoms," says Peter Cochrane, technology commentator and former CTO and head of research at British Telecom.

"The US Army already has spare part printers in the battle zone and Boeing et al are printing over 300 products for their aircraft."

However, the swap to 3D printing won't be quite the overnight sensation some people predict. "We'll still have mass produced manufacture but this will be augmented by 3D printing, both in the home and in the established factory," says Gill. "We're already seeing established brands 3D printing parts for their product lines, to help increase choice, personalisation and to be faster to market."

Having a 3D printer at home will mean it's easier for us to fix broken items and, as Gill believes, "augment existing mass produced products to create new product lines."

New types of self-sustainable businesses using 3D printing could create new markets, though likely such companies will produce products, too; not everyone will be buying a 3D printer.

Curran agrees that 3D printers won't entirely dominate production. "Practical issues dictate that localised 3D printing hubs are more likely than the 3D printer in every home," he says.

"Traditional printers are on their way out due to the proliferation of mobile devices and move towards sharing content digitally," he says, "Due to the diversity of physical elements comprising many real world objects, it makes more sense for bespoke 3D design printing to be handled by specialists."

Some sectors will certainly change. "The days where modelling aficionados spend hours putting together aircraft kits they bought from a store could be long gone," says Shields.

"Instead, the designs would simply be downloaded and the parts then put together at home."

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),