Is Android Google's Achilles' heel?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Just four years ago, the Open Handset Alliance, headed up by Google, released Android, the open source mobile operating system for smartphones (and later tablets).

The first Google phone was the T-Mobile G1.

Since then Android has enjoyed a meteoric rise, gaining popularity in the smartphone market much faster than even Apple's iOS did on its debut. However, that rapid increase in market share isn't the full story.

There are big problems behind the scenes – problems that could turn Android into a poisoned chalice for Google.

The cost of free

First there are the patent wars, which may help its competitors squeeze Android off smartphones and tablets. Major companies like Microsoft, Oracle and Apple are claiming patent disputes against the manufacturers of devices that use the Android operating system.

These disputes are usually so costly to fight, smaller companies will often just agree to pay patent licensing costs to the larger company rather than spend cash confronting it in the courts. This means Android, a free operating system, is suddenly costing the device manufacturer money to use.

Other patent disputes have had an even bigger impact. For example, Apple gained a temporary injunction in August to prevent the Samsung's Galaxy Tab 10.1 from being sold in Europe (albeit temporarily) after Apple claimed the tablet copied the iPad's design and functionality. How long will it be before the patent wars are enough to put manufacturers off Android, particularly if they mean they have to pay for a 'free' OS and may be prevented from selling their devices altogether?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Other Android worries come from consumer complaints about over-complication due to the many different versions of the OS being run by different mobile phone and tablet companies, and how slow some networks and phone companies have been to provide updates.

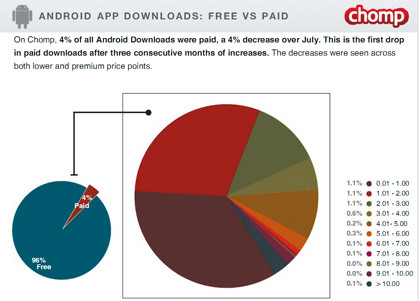

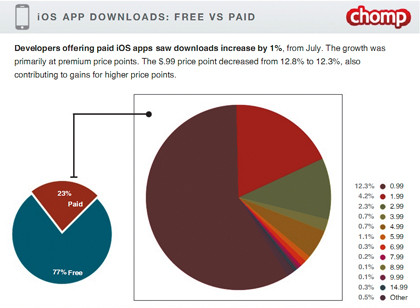

There's also the lack of quality control on the Android app market, questions about just how 'open' Android's open source OS is, and no sign of any money coming back to Google to cover the costs of development and deployment.

Has Google bitten off more than it can chew? Is the attraction of Android starting to wear thin, and if Google's dream of mobile phone dominance goes bad, could it take the rest of the company down with it?

Trouble in paradise

This should have been Android's year. In many ways, the project appears to be a runaway success: it's gaining market share at an unprecedented rate – 550,000 activations a day – and Android app downloads are matching those of the iPhone.

However, it's clear that there's trouble in paradise. There has been a litany of woes since Android's launch, which taken together could be enough to put consumers and manufacturers off Google's OS. But before we can understand the reason for this, it may be worthwhile asking why Google developed Android in the first place.

Google's involvement in Android started in July 2005 when it bought a company called Android Inc, which was founded in 2003 by Andy Rubin, Rich Miner, Nick Sears and Chris White. Android Inc was a little known company acquired by Google along with a raft of other start-ups.

Not much was known about it before it was purchased; Android Inc worked in secrecy then, revealing only that it was working on mobile software. In that year Google was snapping up a large portfolio of technology start-ups, but Android Inc still seemed a strange purchase for a company that had made its fortune in online search and advertising.

Remember, this was at a time when the major phone manufacturers were primarily Nokia, Sony Ericsson, Motorola, RIM (maker of the BlackBerry) and Samsung. Between them, they had the mobile phone market sewn up, each with a band of loyal followers, so the likelihood of other companies breaking into this market seemed slim.

Microsoft, a firm with a lot of money at its disposal, had tried repeatedly with limited success. It wasn't until 2007 that Apple, which was then best known as a computer manufacturer, blew all that out of the water with the release of the iPhone. Phones suddenly weren't just for calls and texts – they became portable computers, and the worlds of mobile phones and computing were changed forever.

Google had clearly anticipated this, and didn't want to be left behind. If the world of the internet was to be re-housed on the mobile phone, it needed to be part of that market. As such, it had been busy as the driving force behind the Open Handset Alliance, initially a collection of 34 companies, from handset makers and silicon chip producers to app developers, including big names like Dell, HTC, Intel, LG, Motorola, Qualcomm, Samsung, Sony, T-Mobile and Nvidia.

Together they wanted to create open standards for mobile phones, and in November 2007 they announced Android, an open source operating system based on the Linux kernel that anyone could use for free. Any developer could design an app for it, without the restrictions that Apple demanded for its App Store.

Where's the business model?

It sounds like a fine enterprise, but the business model behind Android certainly left some people scratching their heads. As well as giving out the OS for free, when it started out Google didn't take any money from revenue generated by the apps on the Android Market. How, people wondered, was it planning to pay its way?

Steve Ballmer certainly didn't get it, and was open about his confusion. Speaking at the Telstra Investor Day conference in Sydney in November 2009, he said: "I don't really understand their strategy. Maybe somebody else does. If I went to my shareholder meeting, my analyst meeting, and said: 'Hey, we've just launched a new product that has no revenue model!' I'm not sure that my investors would take that very well. But that's kind of what Google's telling their investors about Android."

Is Android's business plan as flawed as Ballmer suggests? We put that question to mobile technology specialist Allan Nogee, Research Director for Wireless Technology Group, In-Stat.

"I think that remains to be seen," he told us. "I think if you look back 10 years, Microsoft would also say that its business model was better than Google's on the PC, but if you look today, you would have to question that. Google and Microsoft have little choice on how to move forward when the world around them changes.

They are each sticking with what they know and hoping for the best, but things change. Microsoft won the PC OS wars because PC hardware became a commodity and it was the OS that added value. Then 10 years later, Apple beat Microsoft because of operators subsidising smartphones. You might as well buy a Rolls Royce if it costs the same as the Buick."

This isn't the first time Google's business strategy has confused people, and it won't be the last. With the massive fortune Google has at its disposal, it can afford to take punts on expensive projects – particularly ones that may offer as lucrative a proposition as letting it own the smartphone advertising market.

Google's forays into the world of office tools, email, even video-playing services often look like financial suicide on paper. 'Where is the profit?' most company boards would ask. 'Why are we giving these services away free and not reaping any instant reward?'

But products like Gmail, Google Maps, Google Earth, Google Docs, Google Calendar and YouTube do have long-term value, and with Google's profits from web advertising to prop them up for the foreseeable future, they don't have to be successful straight away.

They also have the benefit of ensuring Google occupies a space a competitor would otherwise take over, with its free offerings generally proving more attractive than paid-for ones. And, of course, each of these services has Google's directed advertising shoehorned into it, meaning there is still some revenue coming back. Not to mention the amount of information the company can collect about individual users.