Is Android Google's Achilles' heel?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Other Android devices have suffered even heavier blows due to litigation, and have been taken off the shelves completely. In August this year, Apple gained a temporary injunction to ban Samsung's Galaxy Tab 10.1 from being sold in Europe.

The sales ban may be lifted now while investigations continue (except in Germany), but the injunction banning the sale of the tablet fell right in the middle of its launch – no doubt costing the company a lot of money in lost sales and colouring the viability of the tablet in the eyes of the consumer. Who wants to buy a tablet which could be discontinued by a court case at any moment?

Each time a manufacturer finds itself in an untenable position from these patent legal cases, it is less likely that it will look to Android an OS it will use in the future. It's obvious that unless Android is placed on a more secure legal footing, smaller manufacturers are going to be put off by the possibility of suddenly being asked to pay for it, or even being shut down for using it.

This seems to be happening already, with HTC, a major player in the uptake of Android handsets, announcing its intention to buy its own OS.

Googorola

In response to these patent cases, and in the hope of protecting the Android-using phone makers, Google may have inadvertently put another nail in its own coffin. Google announced its plans to buy Motorola Mobility for $12.5 billion (£8bn) in August. In doing so, it will acquire 17,000-plus current and 7,500 pending patents, all of which would help provide Google and its partners with protection against those who want to sue them for patent infringement.

However, as well as the patents, Google has acquired Motorola's manufacturing arm, meaning it could easily create its own phones and tablets. Rumours soon spread that Google was planning to wall off its open source operating system and start producing handsets itself. At the very least it would make sense for Google to favour Motorola when it came to seeing pre-release Android code, giving it the insider view that only preferred partners like HTC have had before.

Google was quick to reassure manufacturers, with Andy Rubin saying in a statement that: "Our vision for Android is unchanged, and Google remains committed to Android as an open platform and a vibrant open-source community. We will continue to work with all of our valued Android partners to develop and distribute innovative Android-powered devices."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

But there is little question that a seed of doubt will be sown into the minds of manufacturers when considering whether Android should be part of their long-term strategy. There's another sting in the tail too – the acquisition is being investigated by the Department of Justice due to antitrust concerns. Although this is likely to just be a formality, if it is upheld and the sale is blocked, it could throw Google and Android into more hot water.

We asked Allen Nogee of In-Stat whether buying Motorola Mobility meant Google has shot itself in the foot by possibly putting other companies off using Android. "No, I think the opposite," he says. "The problem was that Apple and Microsoft and others sued the Android manufacturers because that is where the money is. This has been hard and expensive on these manufacturers, and Google could just sit and watch. They wouldn't generally sue Google because it wasn't making anything. These IBM and Motorola patents will help Google fend off these lawsuits.

"There is some fear that if Motorola makes phones it will scare off the other manufacturers, but I don't think that is the case. If they don't make Android phones, what will they make? The Android business is too lucrative."

Tim Shepherd of Canalys agrees: "The Motorola acquisition has certainly caused its other device vendor partners to consider their strategies and level of exposure to the whims of Google. But ultimately, Android has too much potential and momentum right now for there to be serious risk of major defections, helped too by limited and similarly unattractive alternatives.

"Some vendors might also not want to commit too heavily, for instance, to Windows Phone given Nokia's tight relationship with Microsoft. MeeGo offers limited potential and necessitates considerable work, WebOS could be an acquisition target from HP but for now is not a real option, and few other options are available or practical.

"Google buying Motorola is though not just about patents, although that was surely an attraction. Among other things (including useful set-top-box assets, and so on), Motorola also gives Google an opportunity to produce flagship Android devices that showcase the latest updates and innovation on the platform and encourage other vendors to keep up, hopefully reducing fragmentation.

"Yet in reality, other Android vendors will see little difference to the way Google has worked closely with preferred partners in the past, notably with HTC then Samsung around its Nexus One and Nexus S products."

Preferential treatment

As shown by Shepherd's comments, the worry over Motorola getting preferential treatment is a real one. It is unlikely that Google's Eric Schmidt's conversation with Salesforce.com CEO Marc Benioff about the Motorola buyout did anything to calm down the handset manufacturers: "We did it for more than just patents," he said. "The Motorola team has some amazing products."

Previous preferred partners have received a real market advantage over other handsets sporting the updated OS. Each time the preferred partner would get access to all the latest builds and technology, allowing them to create a flagship phone, while other phone companies would then have to play catch up after the newest version was unveiled to the rest of the world.

In the past theses have included HTC with the T-Mobile G1 with Android 1.0 (Angel Cake) and then Motorola with the Milestone (or Droid in the US) for Android 2.0 (Eclair), and later with 2.3 (Gingerbread) came the Samsung Nexus S.

Despite Android's attractions in terms of market penetration, phone manufacturers that were hoping to be preferred partners in the future may now be put off. There is a clear competitive disadvantage in always being behind the curve in the technology, with most consumers likely to plump for the flagship model and those appearing a couple of months later unlikely to catch the public's imagination in the same way.

What's more worrying for Google is that even if it does get to buy Motorola Mobility, possibly putting other Android-using device manufacturers' noses out of joint, it may still not have done enough to protect itself in the patent wars.

Allan Nogee certainly doesn't think so, as he told us when we asked if Google had enough patents for itself and its partners to be safe. "Probably not," he told us, "but it doesn't need every patent. It often exchanges patents, so even if it is missing a few, it can exchange these patents for others that the other company may want. Patents are like a form of currency."

We also asked Tim Shepherd how much trouble the patent wars could be for Google, especially now it is entering the handset field itself with the new Motorola acquisition. "The 'patent wars' in the mobile industry have the potential to be hugely frustrating and costly for Google," he said, "which undoubtedly needs to defend the ecosystem it is building, but its best line of defence is to strengthen its own patent portfolio which it looks to be aggressively doing. Expect to see more IP acquisitions from Google in this area as patents increasingly become real currency in the mobile space."

Too many Androids

Despite Andy Rubin's assurance that Motorola will not become the manufacturing arm of Google, it would make sense for Google to bring Android in-house to, dare we say it, make it more like Apple's iOS – as this would end one of the major complaints about Android today; that of fragmentation. This stems from the way Android is distributed.

The open nature of Android means phone and tablet manufacturers and phone networks are allowed to re-skin Android with their own user interfaces to differentiate their device or service from their competitors'. However, this means that when an Android update is released, users usually have a frustrating wait for the device manufacturer/phone network to develop its overlay to work with the new iteration.

In the past, this meant that updates – even ones that closed security loopholes – took months or years to reach the user, or didn't happen at all. This left an array of different Android versions on phones and tablets, all offering differing levels of functionality, and not all supporting every app in the Android Market.

Consumer confusion can be a major problem in the marketplace, and it's one that needs to be overcome to tempt people away from the cosy simplicity of the walled garden offered by the iPhone and iPad. This fragmentation issue is meant to be being dealt with the release of the next version of Android (Ice Cream Sandwich), which will work on both smartphones and tablets, but is it too little too late?

We put this to Tim Shepherd, asking whether the fragmentation between Android systems, with inconsistent app support and different overlays, means Android is now too big for Google to control.

"Android fragmentation takes several forms: device vendor customisations, Android versions, and a growing experience delta between flagship high-end Android devices and aggressively priced, low spec bargain basement products. Perhaps the biggest implication of this is that consumers' application experiences are negatively impacted and developers have to build for the lowest common denominator, or design apps only for particular Android devices.

"But it also slows innovation and improvements as Android updates take longer to filter down to users. But the flip side is that this is symptomatic of the fact that Android is a highly versatile and scalable platform, in demand from a wide range of device vendors – not least because they can differentiate their products on the platform – and also by consumers.

"Fragmentation is nothing new to this platform, or the mobile platform space in general. Google has to find ways to manage it better to minimise the associated negatives – it is not too late and we are seeing its efforts in this regard with Ice Cream Sandwich. But it must also be careful not to stifle device vendors' creativity and ability to differentiate by cracking the whip too hard."

A fork in the road

However, Android's fragmentation could go too far for Google's liking, taking it out of the company's control altogether. This process is called forking, and it is common in open source software. When two organisations disagree on how to develop the software in the future, the differences can lead to a split with two paths being taken, and two new products created from the same ancestor.

This process often leads to one of these new products being left by the wayside. This isn't just a possibility – it's already happening. Companies like Amazon and Baidu are already taking the open source Android in a direction Google surely isn't pleased about, replacing Google's apps with their own and hiding all signs of the Android OS from view.

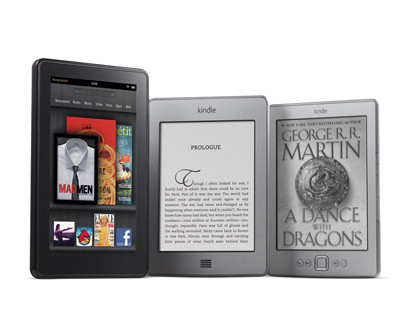

The products are built on top of the basic OS, but all signs of Google have been washed away. For example, Amazon's Kindle Fire, the latest tablet to be offered in the US, is almost unrecognisable as an Android tablet. Not only has it been completely re-skinned with Amazon functionality, including its own apps, there are no Google apps on it at all.

There is a slight positive spin on this for Android, as it means that it can show it isn't taking a monopoly position with Android and so avoid future anti-trust issues, however, this barely makes up for the massive downside. With the Google apps and functionality replaced, the company has no control on what happens on the tablet or smartphone, and this means the whole point of Android – to seize control of the mobile advertising market – is lost.

All those development costs, all that market dominance will be for nothing. Clearly Android has to walk a thin line between owning the mobile market and owning the supposedly open source OS, but once other big players realise there is nothing stopping them making Android's functionality their own, it may be very hard for Google to stop them without going against the ideas behind the Open Handset Alliance.

Too many stores

Further fragmentation can be seen in app stores offered on Android devices. Often, as well as Android Market, there is a store specific to the company behind the device. Some devices even cut out Android Market altogether.

The Kindle Fire is a case in point, as it uses only 'Appstore for Android' – Amazon's US alternative. Here Amazon does something that Google seems unwilling to do – it vets the apps submitted by developers, checking they do what they claim to. Already different pricing structures and deals can be seen between the two app stores, and if this works for Amazon, others will consider similar ventures for themselves, once again taking the control away from Google.

Clearly, if this practice caught on it could cut off a revenue stream that, while currently not very impressive, could build exponentially in the future if Android improved its app store. With all these woes, has Android already had its time in the sun? With no profits expected any time soon, patent wars waged on manufacturers that use it and the OS being used by other companies for their own ends, we asked Allan Nogee if he could imagine a situation where Android would be more trouble than it's worth for Google.

"If mobile advertising revenues don't match those from the PC, that could be a problem," he replied. "This is still an unknown, but Google has no choice, because it knows PC advertising will drop in the eventual mobile world everyone is talking about."

But can he envisage a way that Android could kill Google? "I don't think so. Most of the big costs are likely behind them, so the cost going forward should be less, and you always have to think, what is the alternative? They could pray that PC advertising never drops or continues to grow, but that is a big risk."

Tim Shepherd agrees: "Google is a lot more than just Android. I think it is highly unlikely, but I will say that a substantial reversal of Android's current fortunes over the coming years would leave Google's role in mobile, arguably the most critical future technology space, significantly diminished.

"So, with no choice but to push on with Android, Google has a lot to get right, and a lot of people to fight if it is going to win over the long run. Android may not be about to take Google down at the moment, but it's proving a hard beast to tame and steer. Without strong management and major changes in policy, it's unlikely that Google is going to claim the mobile advertising space it needs to, and in the future, without mobile, Google could be nothing."