AptX unpacked: your guide to using Qualcomm’s Bluetooth codecs (and the devices that support them)

Better Bluetooth audio can be yours, but it’s very much buyer beware

In the ever-evolving world of Bluetooth audio, codecs are responsible for turning your tunes into something small enough to be transmitted wirelessly from your phone to your best over-ear headphones. We need codecs because that Bluetooth link just isn’t robust enough to handle unaltered audio straight from your preferred music streaming service.

Some of these codecs have been with us since the dawn of the MP3 format. They use “lossy” compression, which means they achieve their small size (as measured in bits per second) by removing some of the information from the source audio.

Now I’m going to be honest with you: the default lossy codec that runs on 99% of Bluetooth devices – known as SBC – is just fine for casual listening, as is the second most common codec, AAC. The quality of your source audio and the quality of your headphones (or a set of the best earbuds) will both play a bigger role in the enjoyment of your music than the Bluetooth codec your devices are using. If you primarily listen while on the go, whether on public transit or navigating busy urban sidewalks, you probably don’t need to give Bluetooth codecs another thought. To quote Ferris Bueller, “You're still here? It's over. Go home. Go.”

Better codecs, better audio

However, there are times when you might become aware of SBC and AAC’s shortcomings, especially if you find time to settle down in a nice, quiet spot, and you have access to a source of lossless and/or hi-res audio (read: not Spotify – or at least, not yet).

The good news is that there are better Bluetooth codecs available. Some, like aptX and LC3, (part of Bluetooth Low Energy Audio) deliver better audio quality at similar levels of bandwidth to SBC/AAC, while others are built to support 16- and/or 24-bit audio, with sampling frequencies of up to 96kHz. Some purport to even provide lossless, CD-quality – the gold standard for many audiophiles.

It’s a dizzying list that includes aptX HD, aptX Adaptive, aptX Lossless, LDAC, LHDC, SHDC, LC3plus, and Samsung Seamless Codec (SSC).

The bad news is that device compatibility restrictions can make even a seasoned audio reviewer’s head spin when attempting to access and use these codecs.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

I’m not going to get into the admittedly very nerdy discussions over which of these codecs is hands-down best. Instead, this is a guide to Qualcomm’s family of aptX codecs. Because of all the codecs in that list, they’re the most ubiquitous and also the most confusing.

Compatibility is key

The bottom line with any Bluetooth codec is that it needs to be supported on both the source device (your phone, tablet, or computer) and your target device (wireless headphones/earbuds/speakers), or it won’t work. You’ll still get audio, but your devices will revert to SBC or AAC.

Also, while it might sound self-explanatory, remember that whatever piece of digital audio content you're trying to stream also needs to be of suitably high resolution – so if you're streaming an MP3 file, say (at typically 96 to 320 kbps) using aptX HD-certified source and target devices, it still won't magically upscale to 576 kbps. The file may still sound a little better, because of the improvements to how the data's been transmitted, but aptX codecs cannot restore information lost in an MP3 file.

In summary, the first rule of aptX is: regardless of the aptX version you want to use, that version must be specifically supported. It’s easy to get tripped up here. Some newer versions are backward compatible with older versions, but not always. And sadly, some manufacturers incorrectly state the version that their product supports. There’s a lot of due diligence needed on our part as buyers, and I’ll cover all of the gotchas as we get into each version.

iPhone owners need not apply

The second rule of aptX is: it doesn’t work with iPhones, iPads, or Apple Watches. This includes its AirPods line of headphones and earbuds, and its Beats lineup.

The reason is simple, yet frustrating. Apple chooses not to license Qualcomm’s aptX technologies. Apple believes that AAC (and its lesser-seen lossless cousin, ALAC – or Apple Lossless Audio Codec, which is not supported by wireless AirPods) delivers sufficiently high-quality audio and the Cupertino giant uses it for all of its Bluetooth products.

So even if your new (non-Apple) headphones proudly state that they are aptX Lossless compatible, your iPhone won’t let you hear that improved audio quality. If you want a higher caliber of audio from an iPhone, Apple offers lossless quality via a wired USB-C connection on the AirPods Max (second generation), Beats Studio Pro, and Beats Solo 4.

Every aptX flavour

OK, with those two rules out of the way, it’s time for a quick rundown on the five (current) aptX versions.

AptX Classic: the codec that started it all, aptX Classic (or simply aptX) offers two key enhancements over SBC: better audio quality and lower latency. AptX also has lower latency than AAC and many have argued that aptX’s audio quality beats AAC, especially on Android devices. Like SBC and AAC, aptX is lossy and limited to 16-bit audio sources.

AptX HD: A higher quality version of aptX compatible with audio sources up to 24-bit/48kHz. Because of this, aptX HD is sometimes considered a hi-res codec, but since it also uses lossy compression, not everyone agrees on this point. What can’t be denied is that aptX uses more bandwidth (576 Kbps vs. a maximum of 352 Kbps for aptX), which means more of that precious information is preserved. Unfortunately, aptX HD can’t adjust that bitrate as wireless interference degrades the speed of your Bluetooth connection, which can cause audio dropouts. Backward compatible with aptX devices.

AptX LL (Low Latency): As the name suggests, this is a version of aptX designed to minimize the time between when audio is generated on your source device and when you hear it on your wireless headphones. With latency as low as 38 milliseconds, aptX LL makes fast-paced gaming possible when using wireless audio. Backward compatible with aptX devices.

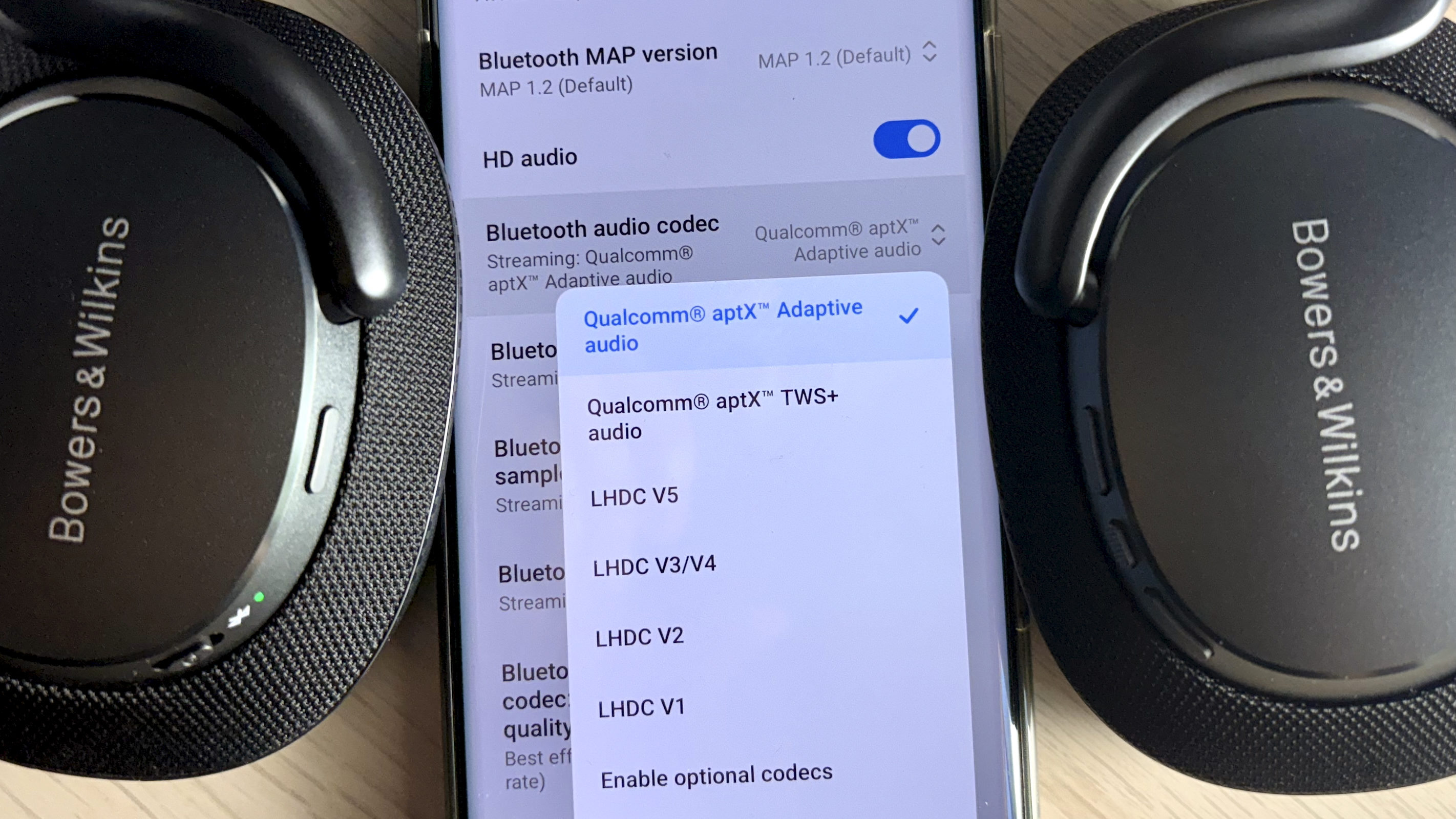

AptX Adaptive: This is Qualcomm’s flagship codec. It’s like a super-set of the three versions above, with the intelligence to know when it should focus on low latency, or when to transmit more data with support for up to 24-bit/96kHz hi-res audio. Though still technically a lossy codec, it can adapt its bitrate to match the quality of your Bluetooth link, offering more audio quality when it can, while simultaneously avoiding dropouts when things get dicey. Backward compatible with all aptX devices and select aptX HD devices.

AptX Lossless: A version of aptX that can deliver 16-bit/44.1kHz audio losslessly, and therefore at CD quality, according to Qualcomm. This requires a lot of bandwidth however – more than a typical Bluetooth connection can support – which is why aptX Lossless requires Qualcomm’s chipsets to be present in both the source and target devices. AptX Lossless is considered an add-on to aptX Adaptive, so any product that supports aptX Lossless automatically supports Adaptive.

Want aptX? Check this chart

The trickiest part about Qualcomm’s aptX technology is knowing whether your gear will work with it. To help answer this question, I’ve created a chart that covers most – but not necessarily all – of the prerequisites for each version. In each case, you’ll need a source and target device that meets these criteria.

AptX version | Source device types and minimum requirements | Target device types and minimum requirements | Notes |

aptX Classic | Android 8.0 or higher devices with aptX Windows 10 or 11 devices with aptX USB A or C dongles, external DACs, or transmitters with aptX | Bluetooth headphones, earbuds, AV receivers, or speakers with aptX | Though not officially supported, it’s possible to force a Mac to use aptX for Bluetooth connections |

aptX HD | Android 8.0 or higher devices with aptX HD USB A or C dongles, external DACs, or transmitters with aptX HD | Bluetooth headphones, AV receivers, or speakers with aptX HD | Not all Android 8.0 or higher devices support aptX HD Due to incompatibilities with primary/secondary earbud connections, aptX HD is rarely supported on truly wireless Bluetooth earbuds |

aptX LL | USB-A or -C dongles, external DACs, or transmitters with aptX LL | Bluetooth headphones or earbuds with aptX LL | Due to incompatibilities with Wi-Fi/Cellular antennas, aptX LL isn’t available on smartphones |

aptX Adaptive | Android 8.0 or higher devices with aptX Adaptive Windows 10 or 11 devices with aptX Adaptive USB A or C dongles, external DACs, or transmitters with aptX Adaptive | Bluetooth headphones, earbuds, AV receivers, external DACs, or speakers with aptX Adaptive | aptX Adaptive requires compatible Qualcomm chips in both source and target devices |

aptX Lossless | Android 8.0 or higher devices with aptX Lossless Windows 10 or 11 devices with aptX Lossless USB A or C dongles, external DACs, or transmitters with aptX Lossless | Bluetooth headphones, earbuds, or external DACs with aptX Lossless | aptX Lossless requires compatible Qualcomm chips and Snapdragon Sound in both source and target devices |

Exceptions exist

The biggest reason that Qualcomm’s aptX world can be so fiendishly difficult to navigate is that the company has always given its licensees the ability to carve out compatibility exceptions.

For instance, even though Google arranged for all versions of Android 8.0 and above to act as aptX and aptX HD sources, phone manufacturers can opt out of one or both. In Samsung’s case, it has chosen to keep aptX on its Android handsets, but not aptX HD.

The same thing goes for manufacturers of target devices. Qualcomm says that all aptX Adaptive headphones are supposed to be backward compatible with aptX and aptX HD. And yet, Focal’s Bathys and Bathys MG headphones – which support aptX Adaptive, are only backward compatible with aptX, not aptX HD.

Simpler with Snapdragon Sound? Not so fast

A few years ago, Qualcomm decided to make the process of identifying compatible aptX products a little easier. It introduced the Snapdragon Sound brand with the intent that if you saw this label on a phone and say, a set of wireless earbuds, you’d know they were guaranteed to work together.

Initially, Snapdragon Sound guaranteed the presence of these Qualcomm technologies:

• 24-bit/48kHz

• 24-bit/96kHz

• Low-latency mode when gaming

• aptX Voice (super wideband voice) when on a call

• Qualcomm Bluetooth High Speed link

A year later, aptX Lossless was added to Snapdragon Sound, but Qualcomm didn’t give it a new version to help identify the products that now supported Lossless. You had to look for aptX Lossless capability in the product specs.

Not long after that, Qualcomm withdrew the aptX Voice requirement from Snapdragon Sound, which further fragmented the label.

At this point, Snapdragon Sound is similar to the HDMI 2.1 specification. It indicates the possible presence of certain Qualcomm technologies, but it’s no longer a guarantee that they’re included. It’s up to us as buyers to read the fine print and determine whether we’ll get what we want.

Tricky, but worth it

If you’ve come this far and you’re still keen to throw together your own aptX-compatible set of devices, I think you’ll find the effort will be rewarded with noticeably better sound.

Especially when using aptX HD, aptX Adaptive, and aptX Lossless, I have found significant enhancements to the level of detail versus SBC and AAC codecs. On some tracks, this manifests as a better separation of musical elements. It almost always reduces the compression in both the highs and lows, letting the music “breathe,” with far more natural sound. I’ve also had instances where the precision of the soundstage lets me hear instrument positioning that would otherwise be smeared.

It might not make a difference when I’m at the gym or listening to podcasts, but in those rare moments when it’s just me and my music, these codecs get me closer to audio nirvana.

You may also like

Simon covers all things audio/video, whether it's reviewing the latest wireless earbuds, or explaining tech terms like spatial audio and PHOLED in language anyone can understand.

He has been covering technology for nearly 20 years; first as the editor of Canada's most visited Science and Technology hub on Sympatico/MSN, then later as a freelance journalist with bylines at Digital Trends, Ozy.com, Mobilesyrup, Driving.ca and VentureBeat. Simon has appeared as a guest tech expert on international TV and radio programs, including BBC Radio, CTV News Channel, and CBC Radio.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.