How bio-hacking is changing your future

From DIY DNA to smart running shoes

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Biohacking is, by way of a definition, a systems-based approach to managing your body. The basic tenet is that by improving your inputs – whether nutritional, physical or medical – you can improve your body’s output.

Sounds simple enough, and in many ways it is – a new fitness regime, a fad diet, or a new Fitbit can all be considered basic biohacking strategies. However, there are an impressive range of more extreme versions out there right now, and we don’t mean hot yoga or personal trainers.

Building blocks

Perhaps most promisingly – and often controversially – genetic engineering is the most extreme example of biohacking: tweaking and manipulating the very building blocks of life. That may sound like overblown science fiction hyperbole, but the reality is very much upon us.

This year should have been a milestone year for ‘genomic services’, with the deadline for the completion of the a UK Department for Health's 100,000 Genomes project, an ambitious plan launched in 2012 to sequence 100,000 genomes from National Health Service (NHS) patients within five years. The 70,000 participants are patients with a rare disease, plus their families, and patients with cancer, in what is the largest national sequencing project of its kind in the world.

The deadline may have slipped a year, but the reality of DNA screening for rare diseases is here today, and the good news is that costs are dropping rapidly. Luckily, so are storage costs – the raw data from one single genome alone tots up to around 200GB, with every genome offering millions of variants from a reference model. The data generated by the 100,000 Genomes project is likely to surpass 20 petabytes alone, which is quite some backup requirement.

Although existing UK data protection laws cover the general principles around medical and personal data, the volume and unique nature of genetic information raises specific challenges. Greg McEwen, a healthcare partner at law firm BLM Law told us: “There are serious questions here around ownership of this data, and the challenges of securing and managing these volumes of highly personal information are considerable.

“If you are on the cutting edge of research of this type, you could for example end up with data that will predict an individual’s risk of developing cancer; if you were susceptible to a serious disease who would you want to know? Your doctor, your work, your insurance company? Would you even want to know yourself? It raises questions that require wider debate – there are no easy answers.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Of course, while central government may not have the best data protection record – the UK NHS’s recent collapse under the WannaCry ransomware attack doesn’t inspire confidence – there are at least solid regulations to build on. And the technology for genetic engineering is rapidly becoming available to all.

Just like some kind of reality-based Dexter’s Lab, you can now causally mess around with the very fabric of life itself in the comfort of your own home. Human genome sequencing might be a little too ambitious for aspiring beginners, but products such as this DIY genetic engineering lab starter kit enable you to can precisely cut and replace DNA sections in a living organism, on your kitchen table. This is down to the marvels of CRISPR/Cas9 technology, which currently runs to manipulating yeast or bacteria DNA.

DIY body printers?

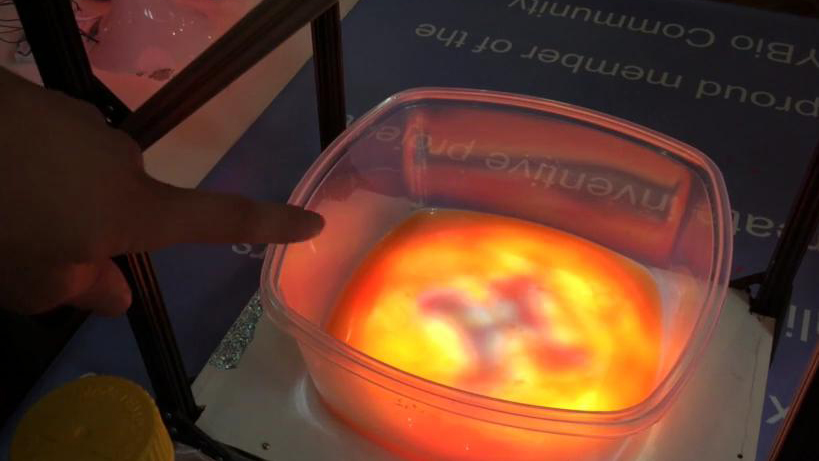

Manipulating bacteria is a strong theme in biohacking. Researchers at the London-based BioHackSpace have created the ‘JuicyPrint’, a 3D printer that uses light-sensitive substrate to ‘print’ in cellulose made by a genetically modified bacteria, Gluconacetobacter hansenii (it uses fruit juice as the initial medium for the bacteria, thus the name).

While the project might look somewhat DIY, the applications for human health are widespread. As the bacterial cellulose is biocompatible and very strong it can be used to create human tissue scaffolds (used in human organ harvesting), the fabrication of artificial blood vessels, and for a host of similar medical applications.

Smarter wearables

Fitness-improving wearables – or, in a bio-hacking context, cybernetic devices – that record biometric data have been around for some years now, and offer the potential to enhance your overall well-being by enabling you to make small improvements to your lifestyle.

Early versions may have been no more than a basic accelerometer in a band, but the latest crop of devices offer far more impressive technologies, lacing together multiple sensors and adding professional-level coaching to provide the essential context to what can otherwise be a confusing muddle of spreadsheet data.

One example is Arion, a combination of ultra-thin smart insoles and GPS-enabled training pods that offers continuous gait analysis and live feedback on the way you run through artificial intelligence (our Running Man of Tech, Gareth Beavis, has already put Arion through its paces).

Meanwhile, competitors Altra have put out the Altra Torin IQ, powered by iFit, a trainer with inbuilt dual footbed sensors and real-time run coaching that offers running intelligence in four critical areas: landing zone, impact rate, contact time and cadence.

Environmental modification

Interestingly, wearables and improved fitness are inspiring new ways of thinking about our everyday environment, and pushing grassroots groups to collaborate and attempt to change those environments for the better.

RunHack London is a group of keen bio-hackers who are aiming to remove as many barriers to running in London as possible, whether that's run-commuting or weekend leisure. The group is the brainchild of Future Cities Catapult, an organization that seeks to improve UK cities.

Scott Cain, Chief Business Officer at Future Cities Catapult, says: “We started out with the question of how we could make our cities more run-friendly, and took the format of a hack-type event. It’s about bringing together tech and wearables and data outputs to get new insights – we had some guys come along who scraped Strava running data and mined that data to show times, volumes and durations – we found out from this that London is the run-commuting capital of the world!

“We’re now working with connecting some of the output from the hack day with public transport representatives and other official bodies. Formalizing these ideas and packaging them up should give politicians the resolve to make decisions that will change the way our cities work for the better.”

The RunHack format is set to reach other cities as well as London, with dates being set for events in Shanghai, New York, Amsterdam and Sheffield.

Overall, biohacking is a broad church indeed, but one that technology is facilitating in a wide variety of ways. From building better, healthier cities around us to printing organs, diagnosing disease earlier to getting our marathon times down, biohacking is alive, well and growing apace – what are you waiting for?

Mark Mayne has been covering tech, gadgets and outdoor innovation for longer than he can remember. A keen climber, mountaineer and scuba diver, he is also a dedicated weather enthusiast and flapjack consumption expert.