Cutting edge: Intel's shape-shifting super substance

Kiss goodbye to static materials and single-function objects

Imagine a world free from material constraints. One in which fixed-function objects and static materials were ancient history. It sounds like science fiction. But believe it or not, researchers at Intel are attempting to create a super substance that will deliver all that and more.

Known as Dynamic Physical Rendering, or DPR for short, it's an incredibly ambitious project that might just revolutionise the way we think about and interact with objects and materials.

The basic idea involves a shape-shifting substance composed of millions of tiny, semi-autonomous units capable of intelligently reconfiguring themselves on the fly to assume almost any form you can imagine.

Currently, of course, Intel's DPR project is at a distinctly embryonic stage. The challenges that the research team faces span fields as diverse as nanotechnology, chip production and complex-system control software.

TechRadar caught up with Jason Campbell, one of Intel's leading researchers in the DPR field, out in sunny Santa Clara, California recently. The conversation that followed was fascinating. In simple terms, the project's aim is to build objects capable of changing shape.

The shape of things to come

"Our idea is to use lots of little parts that can rearrange themselves," Campbell explains. In theory, these individual parts, or nodes, would be tiny, semi-autonomous spheres grouped together into complex systems.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The basic concept involves a system, "that can scale down in size to microscopic nodes and scale up in complexity to millions, tens of millions or even hundreds of millions of nodes."

Size-wise, Campbell reckons things really start to get interesting in the 1mm down to 1/10th mm range.

"We think the most interesting applications for this technology involve interaction with human beings," he says. It's at 1mm and below that the resolution of a material made of spheres becomes convincing for humans, both to the visual and tactile senses.

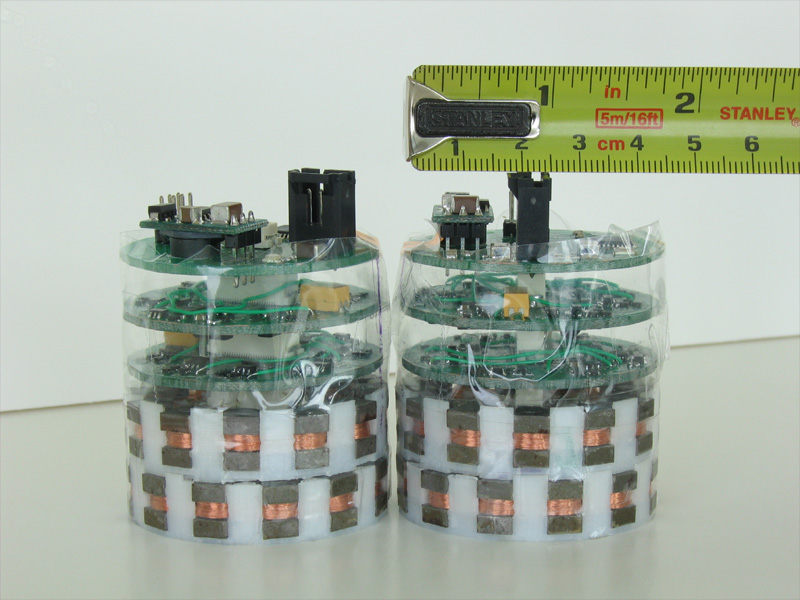

Most of Intel's research since the inception of the DPR project two years ago has involved a two dimensional analogue of the sphere model.

"For research purposes we've been building cross sections of those spheres," continues Campbell. "It makes the initial research simpler to conduct and also makes it easier for us to understand what's going on."

Each of the salt shaker-sized cylinders have electromagnetic actuators placed around their circumference, providing both locomotion and allowing them to retain contact as they "roll" around the surface of adjacent nodes and reposition themselves.

In development

The next step in the development process is already under way.

"More recently we've begun building millimetre-scale devices using electrostatic rather than magnetic fields. In the near term, the aim is to integrate circuitry into 1mm tubes, including an array of actuators and a small control chip, allowing multiple tubes roll around each other's surfaces. The next step from there is to go to full spheres," he says.

Incredibly, Campbell estimates that those 1mm spheres could be up and running within five years. That's right, a sphere which houses a control chip, communications interface, power source and actuators within a 1mm diameter.

Of course, that's assuming he and the DPR team solve the many tough technical challenges. How, for instance, would these tiny sphere's be powered?

"The use of a central power source and surface contacts is an option. But we think there's also enough energy available from daylight or strong artificial light to power these spheres using solar cells on the surfaces of the individual nodes.

"What's more, the nodes could have some translucency to transparency. So, light could penetrate multiple layers deep and power the whole ensemble," Campbell says.

Then there's the software challenge. It's one that Campbell believes will be every bit as hard to solve as the hardware. Controlling potentially millions of individual nodes is a problem of incredible complexity.

Technology and cars. Increasingly the twain shall meet. Which is handy, because Jeremy (Twitter) is addicted to both. Long-time tech journalist, former editor of iCar magazine and incumbent car guru for T3 magazine, Jeremy reckons in-car technology is about to go thermonuclear. No, not exploding cars. That would be silly. And dangerous. But rather an explosive period of unprecedented innovation. Enjoy the ride.