What do your apps want to know about you?

Separating the important facts from the jargon

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Surely there would be an interesting data collection policy here given Tinder is dating app? Is Tinder figuring out what sort of people you like? If you're always swiping right on people with glasses or older people the app could do something clever with that information, right?

The privacy policy doesn't reveal anything too juicy – but what is interesting is that like most (if not all) of the other companies listed here, Tinder says it reserves the right to collect data on you from other sources.

Tinder wonders if you've been using other dating sites

In this case, Tinder is owned by The Match Group which amazingly also owns many of the other big dating websites including Match.com and OKCupid. So if you sign up to multiple sites, Tinder might compile your data together – if not to get you better matches, but to paint a better picture of you to advertisers, no doubt.

Perhaps most interestingly the policy also mentions that Tinder will take a look at your public Facebook profile, if you sign up for Tinder using a Facebook login. The policy says:

"If you do so, you authorize us to access certain Facebook account information, such as your public Facebook profile (consistent with your privacy settings in Facebook), your email address, interests, likes, gender, birthday, education history, relationship interests, current city, photos, personal description, friend list, and information about and photos of your Facebook friends who might be common Facebook friends with other Tinder users."

Whether Tinder actually acts on this data is unclear - but the policy certainly reserves the right to collect it. Given that the object of dating website is to match you with like-minded people, it doesn't take too much of a stretch of the imagination to think how Tinder could improve its matching by comparing likes, background and other data about you.

However, according to most educated guesses, there's no evidence that your data is used in this way - so our guess is that it is the company granting itself permission to access this data just in case it wants to change things in the future.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Conclusion: If you use multiple dating websites don't be surprised if you start seeing some really specific adverts.

Belkin Wemo wants to know if your lights are switched on

Wemo is less well known, but could be indicative of an aspect of privacy that will become increasingly important in the not too distant future: the Internet of Things (IoT). Wemo is Belkin's brand for its connected devices – which covers everything from lightbulbs to plug sockets, to security cameras and other sensors, all of which can be controlled via the Wemo app.

In its privacy policy, it outlines the usual stuff, but also adds that the state of your connected devices could be collected by Belkin. In other words, under the policy Belkin could conceivably see when your lights are switched on, and even when motion has been detected in your house and so on.

In reality the explanation is far from sinister. In fact, it is pretty much intrinsic to how the product works: if you're going to control these devices (both locally and remotely) via an app, they need to send their data to a central server so the app knows how to handle them.

What this does highlight is that as IoT devices become more commonplace, we're going to have to get used to sharing ever more granular details about our lives. If your IoT devices detect heat presence but darkness in the room, don't be surprised if you start seeing adverts on the web reminding you to buy a new lightbulb.

Conclusion: If your house is wired up to the IoT, HAL9000 is already in charge, but to be fair he seems to be doing a rather good job.

Twitter hides in plain sight

Like everyone else, Twitter collects "log data", as well as data from widgets embedded in third party websites. So, for example, if you read a film review that has a Twitter button embedded into it, don't be surprised if you start seeing adverts on Twitter for that film (many other services, including Facebook, do the same thing).

What is interesting to note privacy-wise (and which you might already know) is just how much information you give to Twitter is public but sort-of hidden in plain sight. For example, you might not have fully realised that the list of people that you follow, and who follows you is public. Perhaps more importantly anything you favourite/heart is also public - and this has caught people, including some politicians, out before.

Twitter also logs your location if you grant it access on your device. This means that theoretically your tweets can be geolocated - which might be useful, but also reveal where you are if you don't want to be found.

Conclusion: Everything sensitive is probably already public anyway.

Facebook can use your data in academic studies

Given that Facebook accounts for a large proportion of our lives, there's no doubt that Facebook knows a lot about us. Which is probably why its policy is fairly exhaustive. In among all of the now normal stuff that we expect a service like it to collect, it also notes that it will collect your battery and signal strength. This is presumably so that developers can analyse app processing to check that your battery isn't draining, and also to enable the feature that lets you post offline.

The policy also notes that, like Spotify, your data may be used in academic research. Given the wealth of data, and the fact it could conceivably be segmented by location and demographics and so on, it's no wonder that scientists are keen to interrogate it.

It has already led to some fascinating results – including this paper on the extent to which people with similar political views either stick together or interact with people they disagree with.

Needless to say, Facebook's use of our data hasn't been uncontroversial. In the past Facebook received criticism for not letting users delete data – and even retaining data once accounts were removed. More recently, the company has come under fire for expanding its search capabilities to mine previously unsearchable data.

Conclusion: We already know that Facebook knows everything. Just make sure your privacy settings are set so you only share with the people you want to share with.

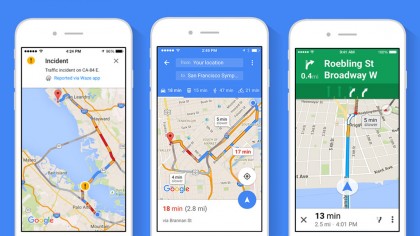

And now the big one: Google. Perhaps it is easier just to assume that Google remembers everything given the company's endless appetite for information.

The company's privacy policy then, is surprisingly brief, and talks about how it collects similar information to the other companies in this feature. This includes your "log" information – like your IP address and device information, as well as "unique" application numbers to identify your device. It also uses the aforementioned pixel tags. So far, so standard.

But interestingly it also notes something that you might not realise is being shared with Google: the times and dates of your calls on your (presumably Android) device, how long they lasted and the "SMS routing" data.

Google also notes that it will log your location information. If you have an Android phone Google will quietly collect data on everywhere you go - and recently even launched a feature that would enable you to retrace your steps. The good news is that if you don't want to be tracked you can switch off location history in settings on your Android device, and delete your existing location history on the Google Location History section of Google Maps.

The policy also says that it will capture data using "other sensors" – including nearby Wi-Fi hotspots. This is something that has caused controversy before when Google tried hoovering Wi-Fi networks up with its Street View cars. The idea behind it is that by measuring which networks are available and the strength of the signal, Wi-Fi networks can be used to geolocate users without GPS – so it will both work indoors, and drain less battery. You don't even have to connect to Wi-Fi for Google to get the data, including each router's unique MAC address.

In terms of how Google uses your data, it's exactly as you's expect: to serve you ads. Interestingly the policy does say that tailored adverts will not be driven by any data Google can deduce about you from "sensitive categories" – which it describes as health, sexuality, race and religion.

What is quite nice about Google's approach – and perhaps we should expect it given the vastness of Google's operation – is that the company provides a whole suite of tools to manage the data that Google contains, so you can download everything or tell Google what specifically to delete.

Conclusion: Google knows everything and in exchange allows the internet as we know it to exist. Whether this will be a fair trade in the long run remains to be seen, but for the time being it is working out quite well.

What have we learned?

Most of the policies are actually rather similar – with all of the apps tending to collect more rather than less data. This is probably for fairly obvious legal reasons: you can sue them if they collect something they haven't warned you about, yet you're not going to be very upset if it turns out that the companies aren't spying on you.

But it is perhaps worth taking a step back and considering just how much data about ourselves and our activities we now routinely share, every minute of every day. The amount of detail these companies – especially the big ones like Facebook and Google – hold about us could conceivably be quite dangerous.

If we want to continue to live in a society that respects the privacy of individuals, we need to become more diligent – and take more of an interest in how much these companies know.