The connected kitchen is a half-baked pie

"Your oven subscription has expired. Pay $49.99 to continue cooking"

For the latter half of the 20th century, kitchen tools stayed pretty much the same. Your basic '80s microwave was still kicking, there were no great strides in saucepan technology, and the fridge was just a humble fridge.

But as the century turned and the Internet of Things exploded into a million pointless gadgets, companies desperately trying to find a new way to sell spoons seized on the 'connected kitchen' idea.

The kitchen of the future, they told us, would do all the hard work. Our appliances would collaborate and cook to perfection, we could shop from our worktops and nothing would ever expire, because we'd get a lovely text with a recipe artfully combining the Doritos, tuna and tinned peaches in the cupboard.

So now that the internet of kitchens has had time to establish itself, why has that tantalising foodtopia not even come close to fruition?

"Sorry, kids, no lunch today. The freezer's bluescreened"

Like much that falls under the umbrella of the internet of things, elements of the connected kitchen can be hilariously facepalm-inducing.

That's not so bad when it's a Bluetooth egg timer you bought cheaply online, but when your smart fridge starts accidentally giving away your Google login details it's no laughing matter – especially as you paid so much more to add 'smart' features to a thing that fundamentally was bought to just keep things cold.

The fact is, connected kitchen products are subject to all the same problems as the rest of our tech, but with some uniquely frustrating consequences.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

What happens when your fridge refuses to open because you're not using manufacturer-approved eggs? Or when your thirsty grandma can't get a drink of water because there's a software update in progress? What happens when your dog is unable to tell you that his Wi-Fi smart feeder hasn't worked for a week and he's starving?

Worryingly, only one of those examples is made up – the eggs. Software withholding drinks has actually happened, and a so-called smart feeder recently left pets hungry when the manufacturer's servers went down earlier this year.

While it's not quite to the level of handing over the keys to their nutrition, it's still quite terrifying to think that some people are giving failure-prone devices control over their food and water.

And it gets worse. Like any connected product, kitchen gadgets are susceptible to security flaws and exploits.

Internet security provider Bitdefender recently found that an unnamed (but popular) brand of smart plug was riddled with security holes, leaving it – and the products plugged into it – vulnerable to remote control by hackers.

"This type of attack enables a malicious party to leverage the vulnerability from anywhere in the world," Alexandru Balan, Chief Security Researcher at Bitdefender, comments in the company's writeup of the issue.

"Until now most IoT vulnerabilities could be exploited only in the proximity of the smart home they were serving; however this flaw allows hackers to control devices over the internet and bypass the limitations of the network address translation.

"This is a serious vulnerability, [as] we could see botnets made up of these power outlets."

And we all know how that could end up...

YouTube : https://youtu.be/T2OpRfLmhHU?t=110

As well as leaving your coffee machine at the mercy of an angry script writer in the Balkans, the not-so-smart plug was broadcasting users' Wi-Fi SSID and password in cleartext, and thanks to its email notification system (which required your credentials for some reason), it would also quite happily give out your email password.

If this is what we're facing from a device that's basically just a socket with a Wi-Fi chip, manufacturers need to do more to improve the security on their larger, more powerful devices.

We all assume that our connected oven is up to speed – but brands need to highlight the efforts made to stopping hackers from firing it up and burning down your house.

It's the same principle as Tesla being forced to explain the work it puts into making sure nobody is going to break into your car's digital brain remotely and drive you off a cliff.

The pattern is almost identical with all technology: if consumers perceive a threat, however unlikely or remote, they're highly unlikely to adopt new gadgets.

But it's not even safety that could scupper the connected kitchen: apply some of the most annoying things about tech in general to your kitchen gadgets and it's not hard to imagine what could happen if viruses or poor business management come into play.

Your dishwasher's manufacturer goes bust, so your 'lifetime' subscription is now defunct – and it won't work without one. Your kettle isn't as secure as it could be, and some teenage hacker realises it can send script to give it ransomware, so it refuses to make any more tea until you pay up.

Imagine having to apologetically tell your dinner guests that your oven can only make half the meal because it hasn't got the update to Android Roast Beef and the grill section doesn't work.

Are these problems we want? Fridge fragmentation? Chefs having to provide eight different versions of a recipe depending on which manufacturer's ecosystem you've bought into?

"Hey Cortana, what's for dinner?"

The surprising thing is that, despite the above concerns, people are still desperate to connect their kitchens to other things – and in fairness, it can actually make things better.

The company who made the quite useful smartphone kettle has graduated to cameras that let you look in the fridge when you're not at home; to some, this is an unnecessary expense, but when it saves you from buying something you already had in there when you're out and about, the seemingly-extravagant cost doesn't seem so bad.

Then again, we're still waiting for LG's explanation for actually designing a fridge that runs Windows 10, because it presumably wasn't "we thought kitchens would benefit from mandatory updates at the worst possible times".

And kitchen gadgets face the same credibility problem that many other tech products have run into initially: they seem to have been invented to solve problems that no one has ever actually experienced.

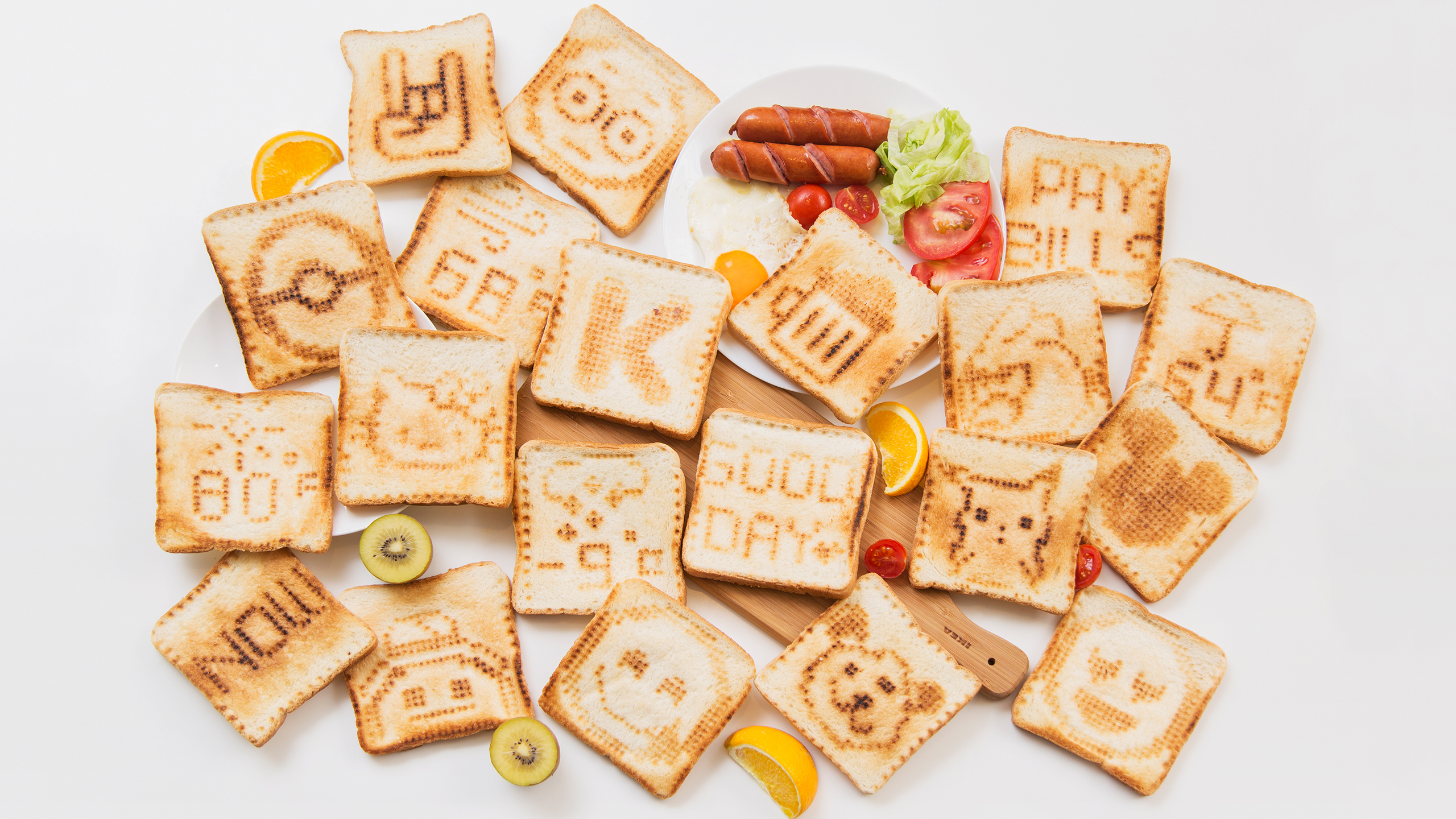

Should a $700 Wi-Fi juicer exist? You'd think not, but it did raise $70 million in funding. Would you sacrifice evenly-warmed bread if it meant your breakfast featured a low-res LOL emoji? It turns out that so many would that the Toasteroid raised almost $200k on Kickstarter.

You could argue that it's depressing to think there are important, world-changing problems the tech industry is reluctant to address, and then find that a lunchbox with its own app has raised a million dollars – but people like the idea of having their food somehow connected to the internet.

Like so many Internet of Things devices, the potential and the demand are clearly there. There's so much good the connected kitchen could do – reduce food waste, prevent house fires, improve nutrition – but we need to get past the stage where some manufacturers are making fridges that ruin your milk if they reboot, then text you to tell you to buy some more.

We will, inevitably, one day be able to run our kitchens largely from our smartphones. The connected kitchen is a good idea – it's just currently suffering from a case of too many cooks.

Once the initial, and often misdirected, excitement wears off, and the new big thing is adding Wi-Fi to your toilet seat (this may have already happened, but we're too scared to Google it), the concept will mature and we'll start seeing cohesive, thought-through systems coming to market.

In the meantime, however, until you can torrent bacon maybe it's best to keep the internet far, far away from our food.