Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

So, the security services are already wise to the techniques of the terrorist, and the government says it only wants CCDP to target those with real evil intent. Politicians are also fond of saying that if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear, but balanced against this increasingly empty platitude is the growing realisation that there are aspects to our online lives that can be either accidentally or deliberately misinterpreted.

Perhaps, for example, a long-term drinking buddy also spends his evenings writing a blog calling for the overthrow of the state. Is he just another armchair anarchist, or someone genuinely trying to bring about bloody insurrection?

Does your friendship mean that you too share his sympathies? Your surfing history reveals that you regularly read his blog, but what it doesn't reveal is your attitude to the content. Are you part of a subversive cell that regularly meets, or do you both simply share a taste for real ale, and enjoy chewing over why he's wrong?

Supposing you and a few friends hit upon an amazing idea for a product. You obviously need to keep it absolutely secret and vet all communications between each other until you can patent it, get financial backing and make your millions. You know that freelance hackers routinely sell industrial intelligence to the highest bidder, so you use the same secure communication techniques used by terrorists - and monitored by GCHQ. Could your need for secrecy turn you into government targets?

Just to see what all the fuss is about, you surf to inflammatory Islamic websites that advocate jihad against the West. Maybe you're writing an action novel and need an accurate description of such sites for authenticity. Does your surfing record mark you down as an al-Qaeda sympathiser?

Supposing your research also leads you to websites that show you how to improvise crude but effective bombs. Does simply knowing something constitute the intent to commit a crime?

Supposing you travel to the US for a holiday. On arrival, you discover you're on a watch list thanks to intelligence distilled from CCDP intercepts and shared by the UK. You're whisked away and interrogated by Homeland Security about relationships and activities, while your spouse and children fret for hours outside.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

What if you decide to overtly show your opposition to the government's snooping laws by deliberately inserting key phrases into unencrypted emails sent between a mesh of email accounts. What then? Can your misguided attempts at protest end in you being required to prove yourself to a stony faced official trained to disbelieve you - possibly in a foreign country where human rights take a backseat in the war on terror?

To find out, we spoke exclusively to an ex-member of one of the UK's security agencies. Hearing the listener Tony (not his real name) worked for a UK intelligence service for ten years. During that time, he spent time debriefing military and NGO personnel about their time abroad in various hotspots and used intelligence coming from GCHQ.

"The CCDP is in many ways a reaction to the problems that we, and undoubtedly any of our sister agencies had," he told PC Plus. "Cheltenham are fantastic at what they do, collecting intelligence, but it's not their job to analyse it."

But is mass surveillance - basically an ongoing fishing expedition - really the best way of going about things?

"There's a growing shift in attitude on how we collect data for intelligence purposes," says Tony. "Historically we've always collected data with a target-driven approach but that is now seen as being redundant." According to Tony, the real problem is the growing mountain of data that has to be sifted for it to become usable intelligence.

"Channels of electronic communication are increasing at an almost exponential rate. There's a fear that without a 'wholesale capture' policy, something's going to be missed. I don't think anyone is trying to argue that the current quality of data is insufficient, rather that the net (excuse the pun) isn't wide enough."

Tony also advises against deliberately trying to be mistaken for a terrorist as a protest against the government's plans. Dropping deliberately provocative phrases into email and text messages or deliberately making repeated contact with jihadist websites and looking up bomb making instructions may get you pulled in for questioning, even if just to make you realise that it's not big and certainly not clever to waste valuable resources.

"Data forensics always have been and always will be an invaluable, if sometimes inarticulate, tool in the creation of intelligence," says Tony. "Certainly an individual's patterns of communication may come up for scrutiny should it be highlighted as a need to do so, but that's all. I think it's a long shot to say that if you communicate like a known terrorist then you'll be considered one. What we're looking at here is raw data; that data is going to be looked at in these cases, investigated, and a decision will then be made."

So, act naturally and the unblinking eye of Big Brother will pass you by unnoticed, it seems. Your casual acquaintances are not interesting, and the security services won't necessarily read anything into them, it seems.

But what about the issue of the security services sharing all their gathered intelligence with other foreign powers? "Historically we don't share 'raw data' - there's legislation to prevent that," insists Tony. "The intelligence that is created from it, however, is highly likely to be shared within the same circumstances as current intelligence is. I don't imagine there's going to be a distinction within any of the intelligence services that certain intelligence was created using CCDP gathered data or not."

So, why not just target social media instead of vacuuming up everything we do online? "While we are successful in our current operations, the growth of networked communications means that it's becoming increasingly difficult," Tony argues.

"Today's major changes may well just be Facebook and Twitter, but targeting social media platforms doesn't legislate for tomorrow's [changes in technology]. This really is intended as a 'Grab everything we can and work out what to do with it later' process. The biggest risk is that the data, and supporting (but possibly irrelevant) data is included with that intelligence and shared."

Eyes on your data

It's important to understand that if anyone currently wants to read beyond the headers of email or SMS messages, or to listen into phone calls, they require a warrant issued under the Regulation of Investigative Powers Act (RIPA), which was set up to strengthen terror laws and to ensure that snooping powers are not abused.

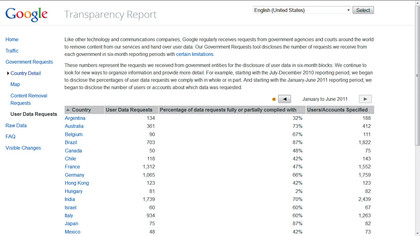

Because of the need for secrecy, total figures for the number of access requests are impossible to pin down, but Google's Transparency Report sheds some light on the situation. This details the total number of requests the search giant receives worldwide, including the numbers of users or accounts specified in the warrants and the number of requests complied with.

The latest figures are for the period January to June 2011. Not surprisingly, the US led the field with 5,950 requests for the content of emails sent and received by 11,057 individuals. Google complied with 93 per cent of these requests (a total of 10,293) either in part or in full.

The UK made 1,279 requests during the same period covering 1,444 individuals. Google complied with just 63 per cent of these (805 requests). The frequency of requests for access under RIPA and the range of groups with the authority to make them come as a shock to most people.

In 2008, the head of the Local Government Association, Sir Tony Milton had to tell local councils to reign in their investigators, who were using legislation to investigate cases of dog fouling and littering.

So, who will have access to the CCDP intelligence pouring out of GCHQ? The list of bodies that can request information through RIPA stretches from the Charities Commission to the General Pharmaceutical Council, which regulates dispensing chemists.

What worries opponents of CCDP is a potential scramble to register for access as there was under RIPA. "The new law does not focus on terrorists or criminals," says David Davis MP. "It would instead allow civil servants to monitor every innocent, ordinary person in Britain, and all without a warrant. This would be a massive, unnecessary extension of the State's power."

"All we're doing," insists Nick Clegg, "is updating the rules which currently apply to mobile telephone calls to allow the police and the security services to go after terrorists and serious criminals, and updating that to apply to new technology like Skype for instance, which is increasingly being used by people who want to make those calls and send those emails."

From this, we can see that the police will also be recipients of GCHQ's intelligence and that Skype will be monitored despite using secure 256-bit AES encryption end to end. Real-time access to conversations will still require a RIPA warrant, though how anyone will decrypt it without the correct keys remains a mystery.

We asked Tony whether it's possible that other bodies might also be given access to the intelligence extracted under CCDP. "The truth of the matter is that it's a certain possibility," he told us. "The legislation that is created to embody CCDP is going to need careful scrutiny and I would hope to see something a little tighter than [current legislation]."

Democratic issues

According to Dr Todd Landman, Professor of Government and director of the Institute for Democracy and Conflict Resolution at the University of Essex, CCDP marks a continuation in the global scramble for data about private individuals. "There are huge implications to the government's proposals," he insists. "In the war on terror, governments around the world have sought to enhance their power to intercept, collect and use private information."

Professor Landman worries about the level of supervision under which those with access to CCDP intelligence will work. "The claim is that the government merely wants to collect information on senders, receivers, date, time and so on, from which they will then build a case for a judge to issue a warrant that then allows access to full content of correspondence. The key question is the degree of judicial - or parliamentary - oversight that is built into the system to prevent the unaccountable use of the new power."

There's also the issue of intelligence being shared across international borders. "The problem is that international law tends to be about the relationship between a state and its citizens, but [the law] is not clear about sharing data between states," warns Professor Landman. "There are also EU directives about data protection that will be undermined by this new proposal."

"The whole plan needs parliamentary oversight," concludes Landman. "Regular reports from intelligence agencies on the use of the power and a special committee to oversee its use. That solution is paramount and it is up to the Lib Dems and Labour to do it, although Labour would have passed the same stuff."

Data overload

Criticism of CCDP also extends to the technological challenges of simply processing so much information about a population of over 60 million people. Is it true that every telecommunications company and ISP will be forced to install some kind of 'black box' on its backbone to perform deep packet inspection? And how will the mass of gathered data be kept secure from hackers while being accessible by GCHQ.

"As far as my understanding has it," says Tony, "under CCDP there would be no 'black boxes' - the data gets sent to Cheltenham almost immediately, or at least routinely. The EU Data Retention Directive is currently worming itself into our legislation and requires that ISPs keep records for however long it is. There's no word as yet as far as I'm aware that CCDP would require them to keep it also after having passed it on."

Home Secretary Teresa May also seems to confirm that there will be no centralised database. Writing in The Sun recently, she said: "There are no plans for any big Government database. No one is going to be looking through ordinary people's emails or Facebook posts. Only suspected terrorists, paedophiles or serious criminals will be investigated."

Tough questions

So, reading between the lines, it seems that there will be a process of temporarily gathering data and sending it to GCHQ, who will extract intelligence in real time before deleting the data to make room for new stuff. If there's no storage involved, the politicians aren't lying when they claim that they're not building a database about us.

The UK's security agencies undoubtedly face a tough job keeping us safe from future terrorist atrocities. How this situation came about is debatable, but what's clear is that we're at a point where difficult decisions need to be made about the balance between privacy and public safety.

The problem is, without clear information about what it is the security services are trying to do, and because slippery politicians are involved in pushing through legislation, public cynicism is high. Perhaps most worrying aspect the government's proposals is that we still don't know exactly who will have access to CCDP intelligence, and to what uses those bodies will try to put it. If RIPA shows us anything, it's that people will keep pushing the envelope of acceptable use until a scandal breaks.

Then there's the Data Protection Act, which says that personal data can only be used for the purpose for which it was collected, and that it must be deleted when that use comes to an end. But do current data retention laws also cover intelligence derived from the original data?

Balanced against these questions is the fact that a tiny fraction of our fellow countrymen actively want to commit murder on as large a scale as possible. Identifying them in a sea of 60 million people is something that will soon affect us all. How much it affects us, however, is something we still have a chance to shape.