How technology is changing what we remember

Is tech helping human memory or hindering it?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I’m supposed to be making sure I can use the term ‘down with the fourth wall’ in the context I want to. But within a few seconds I’ve found an article titled ‘25 Classic Moments When Movies Broke the Fourth Wall’ and within a few more I’m learning that The Big Short enlisted Anthony Bourdain and a metaphor around a seafood stew to explain what a collateralized debt obligation is.

That’s great. Within a few more seconds I’ve saved all of those things, and I can continue back on my original path, finding out more about the fourth wall usage.

If I were reading a book, it would be the same as using a contents page to search for the relevant chapter, finding a more compelling chapter title, skim-reading that for a few pages, and then returning to the task at hand.

This way of learning hasn’t changed all that much; yet there is a growing concern in contemporary neurological studies around what is changing. With vast plains of external memory now available, can the human brain afford to be purposefully forgetful?

The Google effect

Gone are the days when we needed to remember phone numbers, house numbers, birthdays or appointments. The details we need access to require a lot less context, and virtually no mapping out of information. Your brother’s house number, the other names of your girlfriend’s family in case they pick up the home phone, even your Nan’s birthday – forgetting any of these will no longer leave you stranded in a social quagmire (although you should probably try and remember that last one).

The reliance that we place on our brains to accurately recall information is in decline, while the bond we form with technology that can outsource this information strengthens.

Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips , a landmark 2011 report printed in the magazine Science by Betsy Sparrow, Jenny Liu and Daniel Wegner, found that “[The Web] is an external memory storage space, and we make it responsible for remembering things”.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

In one of Sparrow’s studies, two groups of undergraduates were given trivia statements. One group were told they could retrieve the information later on their computer, while the other were told they wouldn’t be able to check back. The first group had worse recall than the second, suggesting that our brains are learning to disregard information found online.

This effect, as with the plasticity of brains, becomes stronger each time we experience it. The more we turn to Google for our answers, the less likely we are to retain what we find there. Instead of remembering a fact, Sparrow’s findings suggest that internet users have learned to remember how to find a fact.

Phone a friend

The good news is that our brains have never been that adept at remembering. Instead, we’ve historically used a technique called transactive memory, a term Sparrow’s peer Wegner proposed to signify the group mind (or hive mind, if you’re insufferable).

A transactive memory system is a mechanism through which groups collectively encode, store and retrieve knowledge. According to Wegner, a transactive memory system consists of the knowledge stored in each individual's memory, but mixed in with metamemory containing information regarding a teammate's domains of expertise. Effectively, you know what you know, and you know what kind of thing the others know.

A transactive memory system used to mean relying on your local community, whether that was your family or your pub quiz team. Now search engines, Evernote and smartphones are replacing personal contacts as our trusted external memory sources.

How many times have you been at a pub quiz aching to reach for your phone for a quick Google check? That’s your brain deciding that a search engine is a more reliable 'phone a friend' than your best mate.

It’s a subject that Nicholas Carr spends a lot of time on when deliberating over the future of the adult brain in his book The Shallows, published in 2010.

He argues that the internet is exposing the human brain to mind-altering technology, the levels of which haven’t been experienced since the printing press.

Our brains, according to Carr, are being rewired so they can only accommodate superficial understanding. Carr saw the ease of online searching and the distractions of browsing through the web as possibly limiting our capacity to concentrate.

However, with a few years' breathing space from The Shallows it’s actually beginning to look like our brains, plasticity and all, deserve a bit more credit.

After all, they were never specifically ‘programmed’ to read, to make it into town for bang-on 11am, to write, or to use a printing press – we’ve just been able to adapt. In spite of Carr’s claims that we’re drifting into the shallows of comprehension, it’s likely that, inside our heads, something much more complex is happening.

The intelligence race

Contrary to the assertions Carr made in his 2008 article Is Google Making Us Stupid?, futurist Jamais Cascio argued in a 2009 issue of Atlantic Monthly that technology is actually making us smarter. Cascio made the case that the array of problems facing humanity will turn the fight for survival into an intelligence race:

“Most people don’t realize that this process is already under way,” he wrote. “In fact, it’s happening all around us, across the full spectrum of how we understand intelligence. It’s visible in the hive mind of the internet, in the powerful tools for simulation and visualization that are jump-starting new scientific disciplines, and in the development of drugs that some people (myself included) have discovered let them study harder, focus better, and stay awake longer with full clarity.”

It’s now been five years since The Google Effect first made headlines. The idea that the internet can change how we think is no longer new or revolutionary. But the next generation of apps that aid these inventions with claims of total recall are still evolving – and you can bet our brains are too.

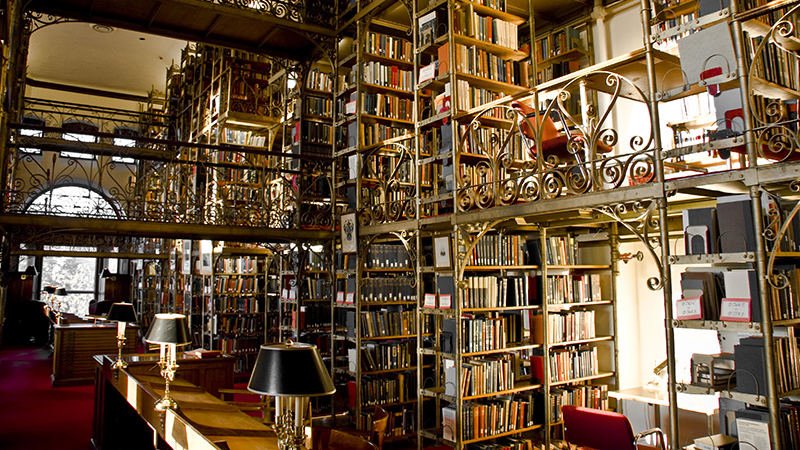

Main image: Cornell University Library. CC image courtesy eflon

Ava Szajna-Hopgood is a freelance writer and marketing and communication specialist with a passion for the creative industries. She worked as Features Editor for Urban Junkies for two years writing weekly trends, restaurant reviews and travel guides.