Linux networking made easy

Common Linux networking questions answered

Ten years ago, most of us thought we would be able to live a full and happy life without worrying about whether we were getting maximum throughput across our networks, or whether the point-to-point latency on our machines would preclude us from popular gaming. But things have changed.

Televisions, games consoles and Linux machines all vie for IP addresses and bandwidth, usually on the same network, with poor wiring, poor layout and do-it-yourself support. Which is where we come in.

The Linux platform is the direct result of this network connectivity. It's an operating system that was designed from the first line of the kernel to talk to another kernel, and as a result, it's the perfect network troubleshooting platform.

You won't find settings hidden, parameters unprobed, or hardware unhinged under the surface, which is why Linux makes both a fantastic training ground for future system administrators, and a powerful ally in the hunt to track down intermittent problems and poor performance.

This is why we've pooled as many of the most common networking questions we could find. The answers should help you better understand how Linux handles the network, what kind of troubles are likely, how to get the best performance and how to create the most stable network in your neighbourhood.

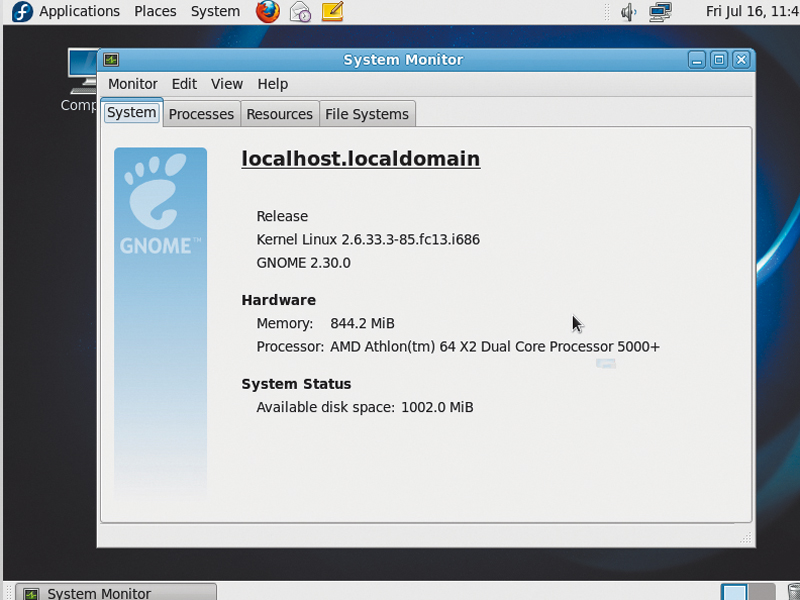

How can I change my hostname?

On the surface, this might sound like a rather technical question to start our networking article with. But your computer's hostname is really just the name you give your machine when you install most distributions.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Ubuntu will ask you for a descriptive name, for example, and this is displayed when you use a login screen or open a command prompt. But it's also the name used for your computer on the local network, and this is why, historically, it's called your system's hostname – the machine that's hosting your current session.

It's also a perfect illustration of how difficult Linux can sometimes be to manage, because with most distributions, there's no longer a GUI for changing something as simple as the hostname.

The old Gnome network manager used to have a field you could change, but this has now gone, leaving users facing either the command line or a tool such as Ubuntu Tweak. Fortunately, making the change on the command-line isn't that difficult, but you do have a couple of choices.

The hostname command should be up to the task, taking the new name as a single argument. But we found that this only seemed to make a temporary change on our system, which left us resorting to the old-school method: editing the /etc/hosts and the /etc/ hostname files, and simply replacing the single occurrence in each of the old hostname with your new new one.

Either way, after you've changed your hostname, you'll need to logout and back in again to see the effect, and for seeing the changes across a network, it's easier just to restart your machine.

How can I share my internet?

Now that most of us use a wireless router to access the internet, sharing an internet connection isn't as much of an issue as it used to be. New machines can either connect wirelessly, or use a spare Ethernet port on the back of the router. But if you do find yourself wanting to share a connection from your machine, there are several different ways you can do so.

If you have two Ethernet ports on your machine, one of which is connected to the internet, you can use the other port with a crossover cable to connect a spare machine. You then need to use your desktop's network manager to enable sharing on the working connection.

Gnome's default network manager includes this option, as does the version shipped with the latest versions of Ubuntu. You also need to use the network manager if you've got two Ethernet cards and only want to enable one. If they're both connected to valid DHCP servers (or are configured manually), and both use the same subdomain, they could conflict with one another.

Fortunately, enabling and disabling connections through the network manager is as easy as either deleting it completely or selecting it from the drop down list of connections from the menu.

How can I set my time using NTP?

Computers are really just big time pieces, yet despite their number crunching accuracy, they're not the best devices for keeping time, especially when it comes to switching between daylight saving modes. And if you travel with a laptop, very few distributions detect a change in location and update the time accordingly.

Of course, if you've got the patience and a decent chronometer, you can easily update the time on your system yourself, using anything from the system BIOS to the little clock that sits in your task bar.

But there's a better way, and it's a way that doesn't require caffeine-enraged reflexes. You can use something called NTP, the Network Time Protocol. This will synchronise your clock with a couple of local servers, and in the process, turn your machine into a local atomic clock. Almost.

If you're a GUI fiend, most system clock applications already include this feature. With the KDE desktop, for instance, you can right-click on the clock within the panel and select Adjust Date And Time. In the window that appears, you now just need to click on Set Date And Time Automatically. This will enable the Time Server field just below, and from there you should select an NTP server closest to your physical location.

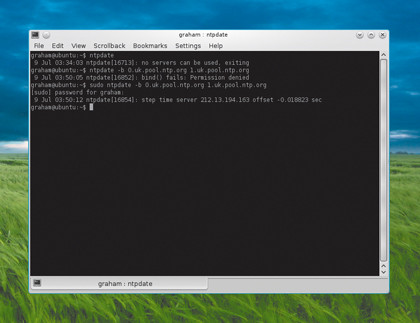

If you prefer to use the terminal, the command you need to use is called ntpdate. It's usually installed by default, but you'll also need the internet addresses of two time servers. The easiest way to find them is to point a browser at www.pool.ntp.org and choose a couple of servers from the list on the right.

Two are needed, because ntpdate triangulates the latency between you and the remote servers to generate a more accurate local reading. For this reason, it also helps if the two servers you choose are geographically close to your current location. It's then just a matter of typing ntpdate -b 0.uk.pool.ntp.org 1. uk.pool.ntp.org, preceded by su or sudo if you don't have the correct permissions to change the time.

You'll see the time update and the output from the command will tell you by how much the clock has needed to be adjusted, which can be a useful indicator of when you should next schedule a time update.

Why do websites sometimes fail to load?

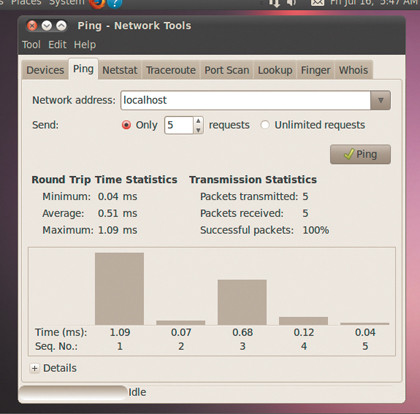

If your network appears to be running properly, but typing a URL into a browser results in nothing but a timeout message, then there's a good chance your problem is within a DNS server. It's the job of the DNS to translate the text-based addresses we use for most servers and websites on the internet to the numeric IP address used by the hardware.

If your DNS is working, for example, you can type ping linuxformat.com into a command line, and the first line of output should show something like the following: PING linuxformat.com (80.244.178.150) 56(84) bytes of data.

If you've not used ping before, it one of the simplest network diagnostic commands you can run. It sends a 'ping' message to a remote server. If the message is received, the remote server sends a 'ping' message back. Believe it or not, the name comes from the sound a submarine's sonar makes as it maps a surface.

You can see in the output of the command that the DNS has transformed our request for the Linux Format server into an IP address (80.244.178.150), and this is the first test you should try if you suspect you've got problems. It's also worth knowing the IP address of a server, as this can be used instead of the URL.

If ping requests are returned from an IP address and not from a URL, you've almost certainly got a DNS problem, and the best solution is to change your DNS. These days, your DNS server is mostly configured through the DHCP server that provides your computer with an IP address.

For most home systems this means your router, and it's also likely that the DNS server itself becomes the address of your router, which means that the first place to look if you want to change it is your router's configuration web page.

After you've found the location of the DNS configuration, use ping to check whether the IP address is still working. If not, check with your ISP to see whether this address has changed. If it has, just replace the old address with the new one. If not, you could always replace the old DNS address with a public server, such as those run by OpenDNS and Google.

OpenDNS addresses are 208.67.222.222 and 208.67.220.220. Google's are easier to remember – 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4 – but both promise to speed up the time it takes for your computer to get the IP address from a URL.

You can also change the DNS on a per-machine basis, and the graphical network configuration tool for your desktop should include the ability to modify the DNS server you're using. If not, the file you need to edit is called /etc/resolv.conf.

Newer distributions that rely on DHCP may not create this by default, so you'll need to create the file yourself. It should just contain something similar to the following:

nameserver 8.8.8.8

nameserver 8.8.4.4

As you should be able to see, we've used the IP addresses of Google's DNS service, but you could easily replace these numbers with the ones for OpenDNS, or even your own router or gateway if that gives you the results you need. Either way, before you'll feel the effect of any changes, you'll need to either restart your machine, or the network (try service networking restart).

Why isn't my USB modem working?

USB modems, of the old dial-up kind and the newer ADSL kind, are mostly dumb. All their functionality is loaded at boot time into the general-purpose processor running inside the box, and without a driver, these boxes can't function.

This is why so many USB modems don't work with Linux, because it's not a simple case of needing to reverse engineer the driver – it's a case of developing all of the modem's functionality from the ground up.

The exceptions are when the firmware for the modem (that's the code that runs on the processor) is made available. A Linux driver can then upload the code to the modem, which should then function perfectly. The only problem is that manufacturers are often reluctant to allow their firmware's to be redistributed, and the binary redistribution of firmware irks many free software advocates.

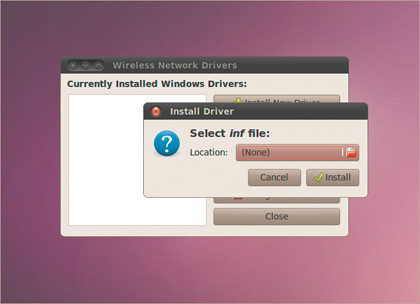

If your modem isn't working, this is likely to be the problem, and the best solution is something called NdisWrapper. This enables you to use Windows XP drivers for your device within your Linux environment. But before it will work, you have to first locate the .inf and .sys files hidden within the Windows driver package.

The best way to tackle this formidable task is to head over to the NdisWrapper wiki and search for your hardware. If your particular device is listed, you should find instructions on how to locate the files you require. It's then just a case of using either the command line or the GTK front-end to locate the files and install the driver.

After which, your system should detect and configure the hardware in exactly the same way as it would have had it installed a native driver.