Capturing the mundanity of humanity: the rapid rise of live-streaming

Sandi Thom’s “I Wish I Was A Punk Rocker (With Flowers In My Hair)” was a flop when it was released in October 2005. That it ended up topping the charts after it was re-released eight months later was down to the novelty of livestreaming.

Her 21 Nights From Tooting tour was, as the name implies, 21 gigs performed over consecutive nights from her basement in Tooting. Each show was streamed live over the web, which proved an irresistible gimmick for DJs and news reporters alike.

It didn’t matter that there was never much proof, beyond the say-so of Thom’s PR team, that her audiences each night numbered into the hundreds of thousands - it was a great story to tell each time before pressing play in the studio.

This was an era where most British people didn’t have broadband, after all.

These days, we’d call it going viral. Thom pulled off a one-hit wonder by exploiting new digital distribution technology, just as the Arctic Monkeys had built a huge fanbase before the release of their debut album by encouraging fans to share MP3s of their demos.

Livestreaming: punk or novelty?

Not to say that there weren’t people who saw past the novelty of the livestreams to what was being sold beneath - Charlie Brooker, besides (charmingly) calling Thom “the musical antichrist”, demanded in his Guardian column to know where all these supposed viewers were hiding.“If her sudden rise to stardom wasn’t the end result of a shrewd marketing campaign,” he wrote, “the implications are terrifying.”

They were terrifying, he argued, because “Punk Rocker” wasn’t “art”, it was “content”. Of course, besides this being just a standard old-man-yells-at-cloud argument against anything not to one’s own personal taste, it does misunderstand why the idea of streaming gigs was such a compelling one for so many people (even if they didn’t end up ever watching them).

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

They were an intimate thing, directly accessible by anyone. The quality of the song was besides the point.

A huge amount has changed in the 10 years since, but we would argue that that sense of intimacy and directness is still crucial to understanding the appeal of livestreaming as it exists now on social media, as opposed to the livestreaming which is boring and ordinary and has been everywhere online basically as long as the web has existed.

That means the tools which appeared, in rapid succession, from Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, after the streaming app Meerkat became the smash hit of SXSW in March 2015.

Twitter saw fit to bring forward the launch of its own streaming app, Periscope, in response, in turn killing Meerkat almost overnight, while YouTube and Facebook also pushed new, long-planned livestreaming capabilities.

Ordinary people doing ordinary things

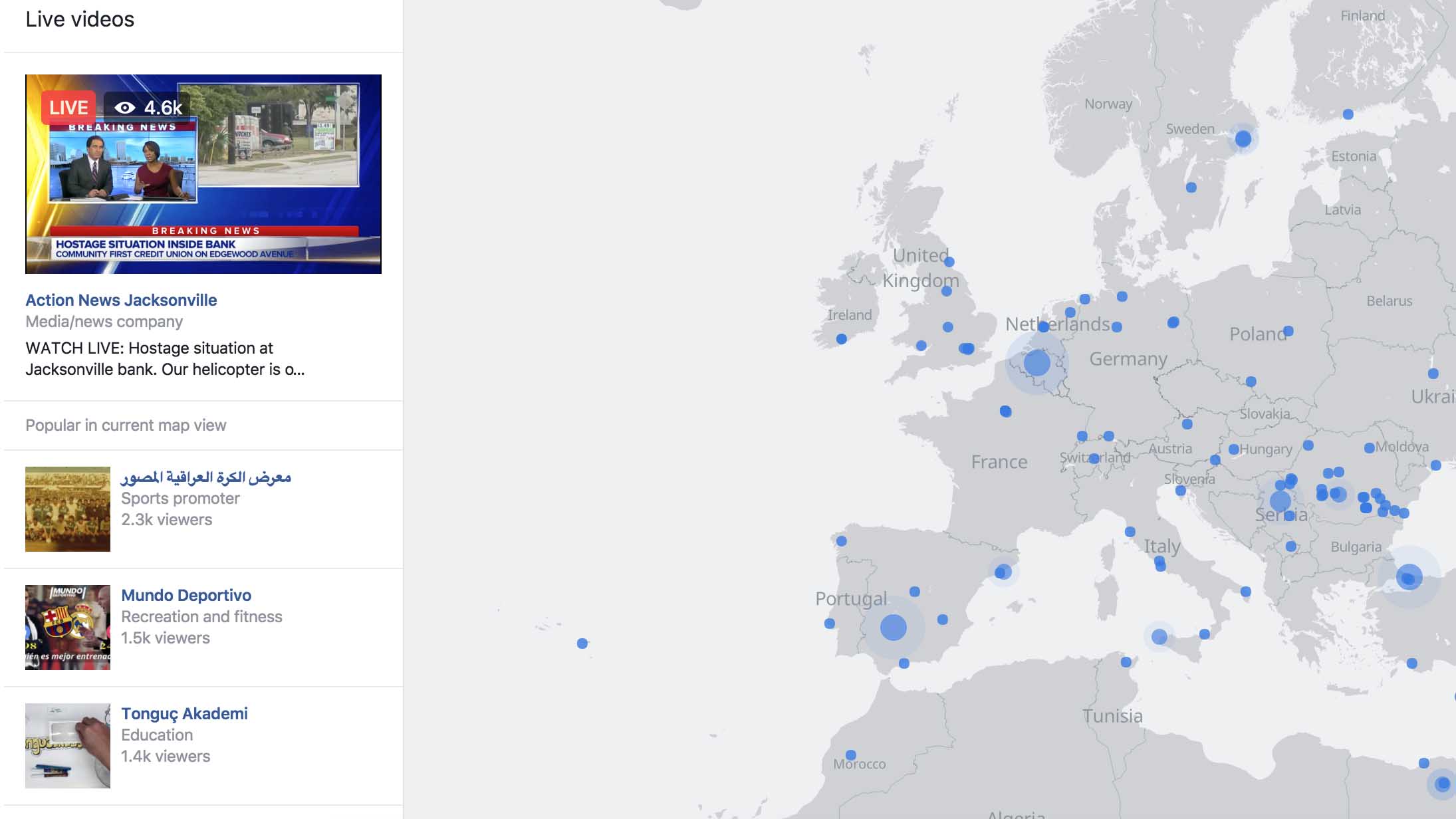

Facebook has a map of public Live broadcasts happening across the world that you can check in on at any time.

This is the best place to start when trying to understand why livestreaming is appealing to some who like to broadcast, and many more who like to watch. It’s fascinating, because it’s humanity.

Yes, there are celebrities on there doing what are essentially live vlogs or whatever because they’ve been paid for it, but it is at its best when watching perfectly ordinary people doing perfectly ordinary things across the globe.

Here’s what was happening in the first five videos clicked on, at random, when writing this piece:

- Some Morroccan dudes hanging out in a house, smoking a shisha pipe

- A woman in London giving a makeup tutorial in her bathroom

- Another woman, in Paris, delighted about how her baby shower was going

- A stream from inside the studio at a Buenos Aires talk radio station

- A student with long, wild hair answering viewers questions from Yangon

None of these people were broadcasting to more than a hundred viewers at once; the viewers they do have, judging from the comment boxes (what’s been posted in English, that is) are rubberneckers, walking down a residential street, gawping in on each window as we pass.

Yet the scenes in each of those windows are also illuminating for what they demonstrate about what these services are actually useful for, as opposed to what the companies that provide them might prefer.

Many of the streams on Facebook Live’s map are illicit re-hostings of professional sports or live TV streams. Half the people streaming from the UK after nightfall seem to be running pirate radio stations from their bedrooms, too.

The personal videos have a sense of presence that makes livestreaming a cousin of sorts to both virtual reality and Snapchat - formats which offer windows into other lives, either brief or in 360 degree.

Think of music livestreaming site Boiler Room’s plan to open the world’s first VR club next year, where anyone can “go clubbing” by sitting on their sofa with a headset; or of DJ Khaled, lost at sea on a jet ski.

No matter where you are in the world, if you’ve got a net connection, you can become an immediate observer of someone else’s story by opening their unlocked window and leaning in.

Broadcasting for all

Yet what livestreaming really represents is the democratization and pseudo-decentralization of the kinds of broadcasting infrastructure which used to only belong to television stations.

And, just as the ’90s desktop publishing boom meant anyone could slap some clipart on a piece of A4 and call it a newspaper, the ’00s livestreaming blitz seems to have brought with it a chaotic mix of low-budget broadcasting formats.

Controlling that low-budget aesthetic properly is what matters to making a livestream compelling, and there are examples to look to.

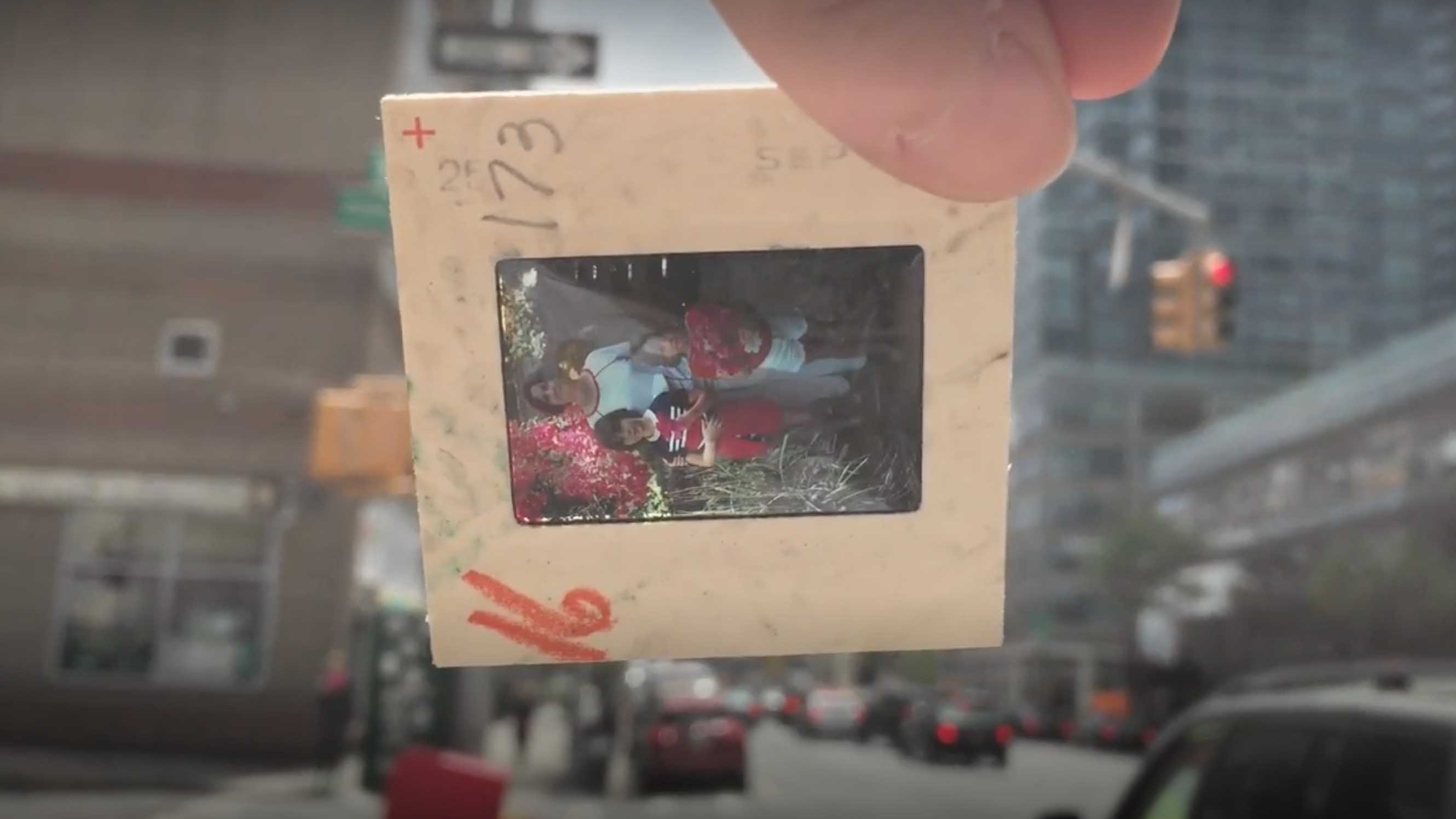

New York Times reporter Deborah Acosta found a garbage bag filled with color slides on the sidewalk earlier this year - instead of searching through them, investigating their provenance, and coming back later with a written piece, she instead whipped out her phone and livestreamed her initial reactions to each new memory held up against the sunlight during the middle of an otherwise normal day.

It made the discovery into an event, and her followers into co-detectives.

It became a whole series of livestreamed events - like Acosta on the phone, calling through the phone book, trying to reconcile fragments of names with these fragments of a life. That the slides turned out to be the property of a renowned author and naturalist was a lucky coincidence from a journalistic perspective.

They could have belonged to anyone; the low-key intimacy of going through someone’s trash and finding forgotten beauty was the difference between a compelling story and a misdemeanor.

The stars of the livestreaming age will similarly be those who can shape new kinds of raw intimacy into such stories.

Of course, this could all be one of those cases where the more things change, the more they stay the same.

In November last year, Sandi Thom took to Facebook in an infamously emotional video to complain about her latest single not being picked for both Radio 2’s and the Bauer Network’s playlists, thereby kneecapping its sales potential. It wasn’t a live video, but it was the same kind of appeal to the public as her 21 Nights From Tooting gigs, 10 years ago.

This time, much of the public responded with laughter - the social conventions of the online world are different now, and arguably colder. Honesty, and intimacy, can’t always be enough.

Ian is a London, UK-based writer and producer who specializes in exploring the intersections of culture and technology. He was previously on staff at Wired UK and The New Statesman, while his work has also appeared in Quartz, The New Republic, Wired US, Techradar, Ars Technica, The Next Web, and beyond. From 2015 and 2019 Ian was also the editor of How We Get To Next.