Meet the real-life human cyborgs

Digital eyes, USB fingers - implants aren't just for Jordan

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Arms and the man

Sadly the "bionic arms race" owes much to a very real arms race. In 2005, the US military announced a multi-million dollar investment in prosthetic technology after a surge in the number of US soldiers losing limbs in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Improvements in body armour technology mean that attacks that just a few years ago would be fatal are now survivable - but the armour doesn't protect limbs.

Inevitably the military isn't just interested in rehabilitating injured soldiers. It's rather keen on enhancing soldiers' effectiveness in battle, too, which is why it's testing exoskeletons.

Earlier this year, Lockheed Martin inked a deal with Berkeley Bionics to develop the HULC - Human Universal Load Carrier - "to provide soldiers [with] a powerful advantage in ground operations." [PDF]

STRONGER SOLDIERS: The HULC exoskeleton isn't sci-fi: Lockheed Martin is working on it with the US Military [Image: Lockheed Martin]

The big problem with such technology is that it needs power. Military versions are powered by battery packs or small combustion engines, while civilian prosthetics tend to use batteries.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

That might change. US and Canadian scientists have found a way for prosthetics to generate power. As Dr Douglas Weber of the University of Pittsburgh told the BBC, "All of the new developments in prosthetics require large power budgets. You need power to run your neural interface; you need it to run your powered joint; and so on."

The solution? A modified knee brace that uses regenerative braking technology to turn movement into electricity.

Tech on the brain

Professor Kevin Warwick - dubbed "Captain Cyborg" by The Register - is famous for headline-chasing ideas such as implanting RFID chips under his skin or attempting telepathy by connecting two people's brains to computers, but behind the headlines he's doing some useful and potentially far-reaching work.

Warwick is helping to develop a new generation of Deep Brain Stimulation equipment, which uses electrodes to make an amazing difference to the symptoms of Parkinson's Disease, and in 2008 he unveiled Gordon the robot.

Gordon is no ordinary robot: he's controlled by living brain tissue. As Warwick explains: "The purpose is to figure out how memories are actually stored in a biological brain… if we can understand some of the basics of what is going on in our little model brain, it could have enormous medical spin-offs".

While Warwick and his colleagues are trying to find out what makes us tick, other researchers are finding new ways of making us shriek.

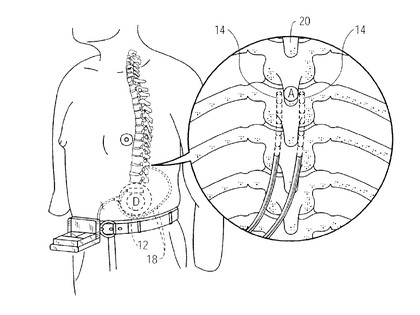

In 1998, Dr Stuart Meloy was implanting electrodes in a patient's spine to make her feel better - but to say he exceeded his remit would probably be an understatement. "You'll have to teach my husband how to do that," the patient told him, moaning with pleasure.

Since then Meloy has been studying the effects of electrodes on the pleasure centres of our brains, and his device - inevitably dubbed the Orgasmatron - will be on sale within a few years.

As Meloy told the LA Times, unlike most medical devices the Orgasmatron won't be tested on animals: "I don't know how to ask animals 'where do you feel the tingling?' or 'do you want a cigarette?'"

SPINE TINGLING: The orgasmatron stimulates the nervous system to induce orgasm - but don't expect to see it in Ann Summers any time soon

So are USB fingers and extra ears part of our future? Probably not. They're impressive but not exactly essential or even particularly worthwhile, and while military exo-skeletons are interesting in an "eek! Terminator!" kind of way the real advances are medical.

From digital eyes that restore sight to prosthetic limbs that generate their own power, work like real limbs and even provide sensory feedback, technology can repair, replace and possibly even improve upon the human body.

Experiments such as Gordon the robot could shed light on the way our brains work, and in the (very) long term computers may even be able to detect and transmit our very thoughts, enabling us to communicate almost telepathically.

If you think Twitter is pretty tedious now, you ain't seen nothing yet.

Contributor

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than twenty books. Her latest, a love letter to music titled Small Town Joy, is on sale now. She is the singer in spectacularly obscure Glaswegian rock band Unquiet Mind.