Forgotten genius: the man who made a working VR machine in 1957

Wind, scent, vibration – Morton Heilig's Sensorama had everything but success

This commercial failure wasn't a first for forward-thinking Heilig. The obscure invention he patented just before the ill-fated Sensorama looks so eerily familiar, it's hard to believe it was created over half a century ago.

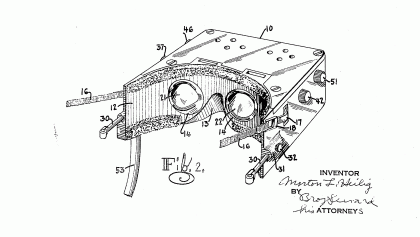

The majority of articles about the birth of virtual reality credit the 1968 Sword of Damocles as the first ever head-mounted VR display. But – as you may have guessed by now – Morton Heilig had something similar a full eight years earlier. His Telesphere Mask, patented in 1960, looks so uncannily modern in the patent drawings that you could be forgiven for thinking it was an early Gear VR.

Described by Heilig in his application as "a telescopic television apparatus for individual use," the Telesphere was in every way a 3D video headset of the type we're used to – except that instead of connecting to a smartphone or PC, Heilig's used miniaturised TV tubes.

"The spectator is given a complete sensation of reality, i.e. moving three dimensional images which may be in colour, with 100% peripheral vision, binaural sound, scents and air breezes," read the patent filing.

And it was still light enough to wear on your head, with adjustable ear and eye fixings. Some modern headsets can't manage that, and this was created at a time when it wasn't even certain the TV feed would be in colour.

Again, the Telesphere was a commercial failure, though it might have consoled Morton to know that a similar digital product was launched on Kickstarter 55 years later and didn't raise even half of its $50,000 funding goal.

So what happened to one of the first head-mounted displays in history? Is it on display in the Smithsonian, or taking pride of place in Mark Zuckerberg's collection?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"I have it in a wooden box," says Marianne Heilig. She dejectedly explains how she personally travelled to a Hollywood museum (without the enormous Sensorama machine - "it's the size of a vending machine"), trying to make the management aware of its significance. She was told they wouldn't even take it for free.

"I've almost given up on this whole thing, but I'm not just going to give it away after a lifetime of struggle. I'm still working just to pay interest on the debt because I refuse to go bankrupt," she says with tremendous dignity.

"It's very demoralising. They'll put on [display] Marilyn Monroe's clothing and shoes, but this is the future, and it started here in 1958. I don't understand the short-sightedness of people," she sighs.

A modern legacy

While Morton Heilig went on to design successful sports products and won the Auteur's Award at the Cannes Film Festival in 1974, he never gained the recognition he deserved for his tech vision. Nor did he live to see the head-mounted immersive reality he foresaw in the fifties come to fruition.

But Heilig and his pioneering inventions haven't been forgotten.

Alex Lambert, Creative Director of immersive experiences company Inition, frequently references the Sensorama machine in his presentations about VR. "It's amazing that someone did this with the rudimentary technology of the 1960s. That's some serious ambition!" he told techradar.

"The Sensorama really stands as the definitive early example of a concept that everyone is striving for: how can we use technology to create alternate realities?"

When Lambert goes on to describe his company's successful virtual reality wingsuit, the echoes of Heilig are stark - and rather eerie: "We added motion, then user-controlled motion and then wind. The wingsuit was a perfect use for VR, as it took something acutely dangerous people would otherwise be unable to do and made it instantly accessible with no training."

But Elliott Myers, creator of the soon-to-be-launched and very Sensorama-like Roto VR chair, says that even after all this time, we still haven't perfected what Heilig set out to do.

"Creating experiential simulators for entertainment (and profits) has long been seen as a holy grail. Alas, limitations of (often physically cumbersome) technology has stifled the delivery of truly immersive experiences," explains Myers. Heilig and his vending machine would agree.

"The current rebirth of VR certainly offers the visual and audio stimulus we've long anticipated. However, just as Sensorama envisaged back in the '60s, tactile feedback (wind, heat, smell and indeed taste) is still some way off [with most head-mounted devices]."

Myers' virtual reality chair uses many of the principles Heilig built into his machine. The motorised gaming seat offers wind, heat, scent and force feedback. The big difference is, the user can tilt and move to control the visuals, whereas Heilig's seat moved for you in sync with the video footage.

So what does Heilig's widow make of modern virtual reality, and its interpretation of his dream? "Just the other day I read an article in the LA Times with the headline 'Virtual reality races on' – it was on the front page. I saved it," she says. Clearly still besotted with the husband she met on a blind date, she adds: "The Oculus and the head gear, it's all very interesting, but Mort had the original."

The unknown genius

Virtual reality is almost certainly not the only development Heilig predicted – but we might never know about the others.

"I have 52 spiral notebooks full of his inventions and a lot of folders as well," says Marianne. "From common things to very imaginative and otherworldy things."

We can only speculate at what wonders those books contain – but again, instead of illustrating a coffee table tome or punctuating a Jobs-style biopic, they remain unsold and undiscovered at Marianne's home.

"I just hope the place isn't going to get a leak in the roof, because one time I had to rescue it all," she adds glumly.

It seems incredible that even in 2016, when the world has woken up to the potential of virtual reality and the prescient brilliance of Heilig's machine, that those drawings and prototypes haven't sold for millions.

That we're not all viewing his sketches in a gallery, or buying tickets to 'Sensorama: the Morton Heilig Story' (in 3D, of course), seems crazy when you hear the reactions to the ahead-of-its-time machine.

But, so often, true genius is seldom recognised until it's too late. Let's just hope by the time Heilig claims his title as the Da Vinci of VR, we haven't lost his other inventions to a leak in the roof.