Forgotten genius: the man who made a working VR machine in 1957

Wind, scent, vibration – Morton Heilig's Sensorama had everything but success

When we talk about the history of virtual reality, we usually refer to the promise of the eighties: the sci-fi movies and experimental products that first made us believe in a virtual world.

From there to here seems an eternity in terms of how far VR has come, but in truth, there have been working VR products since as far back as the 1950s. And one of the earliest still works today.

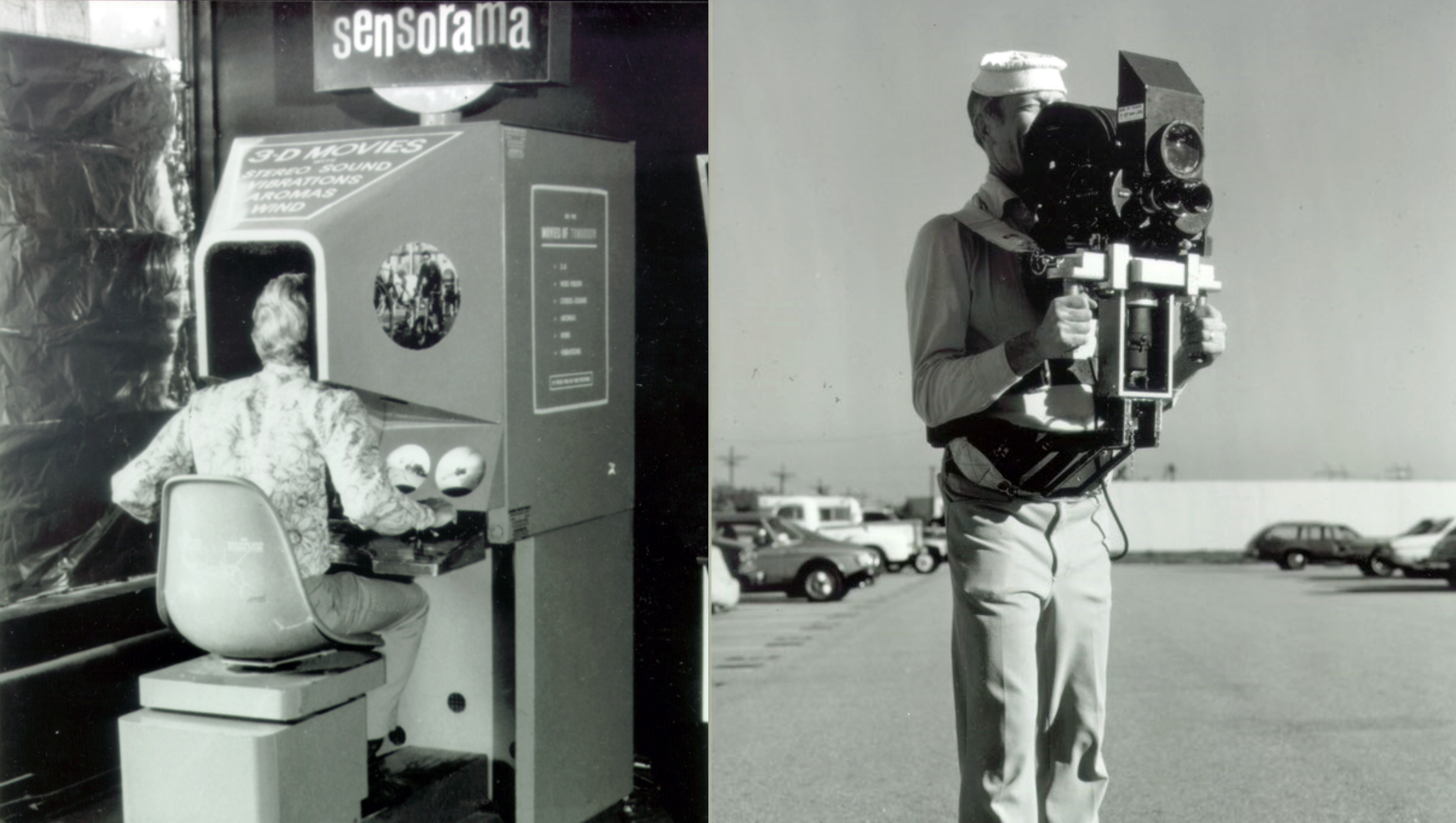

To call Morton Heilig a visionary would be to sorely undersell his brilliance. At a time when most people still owned a black-and-white TV, he hand-built a fully-functioning 3D video machine that allowed you to ride a virtual motorbike while experiencing the sounds, winds, vibrations and even smells of being on the road.

He called it the Sensorama Simulator, and it failed spectacularly.

What Heilig had built was so ahead of its time that it sat unloved by his swimming pool, hidden under a tarpaulin, for generations. His wife Marianne Heilig, who worked with him on many inventions, took on enormous debt to fund his ideas – so much so that she's still paying it off almost two decades after his death. So who was her husband, referred to by many as the Father of Virtual Reality?

"He called himself a Renaissance Man," Marianne told techradar, "because he had so many different talents. When he took me up to the apartment where he had the machine, I kind of oohed and aahed – but I didn't understand the significance of it at the time."

She wasn't the only one. An accomplished cinematographer, Heilig had created the Sensorama out of a desire to build the "cinema of the future." But a 3D cinema required 3D films, which were not easy to come by in the late 1950s.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

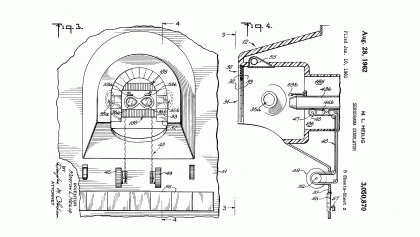

So Heilig invented a 3D camera and projector in addition to his viewing machine, and produced five films to demonstrate the Sensorama's capabilities. These were mostly passive ride-based experiences: a helicopter, go kart, bicycle and that motorbike.

Despite the lack of user control, the films still felt real: Howard Rheingold tried the still-working Sensorama in the eighties and commented that "the motorcycle driver was reckless, which made me very mildly uncomfortable, much to my delight."

The fifth film proved popular with investors, Heilig once joked: it was a raunchy number starring a New York belly dancer. Rheingold notes that the Sensorama would pump out cheap perfume whenever she was near the camera, and the sounds of the cymbals on her fingers could be heard in the appropriate ear. As adult video in virtual reality takes off in 2016, it seems Heilig knew what people wanted before they did.

Selling the future

Morton Heilig could clearly see the commercial potential for his invention, going to great pains to detail potential uses and benefits in his 1962 patent application. The inventor envisioned his machine being used to train the armed forces, industry labourers and students, explaining that "there are increasing demands today for ways and means to teach and train individuals without actually subjecting the individuals to possible hazards of particular situations."

Giving the example of a supersonic jet, Heilig comments that actually flying the jet is a better learning experience for students than just hearing about it, but would be "impossible or dangerous," and therefore his invention would give a better idea of the situation without putting anyone in danger.

"If a student can experience a situation or an idea in about the same way that he experiences everyday life, it has been shown that he understands better and quicker, and if a student understands better and quicker, he is drawn to the subject matter with greater pleasure and enthusiasm.

"What the student learns in this manner he retains for a longer period of time," the patent goes on to say – almost as if Heilig was expecting to sell the machine directly from the filing document.

In reality, the Sensorama was pitched by leaflet to large corporations including Ford and International Harvester, described as a revolutionary new showroom display. Again, Heilig predicted the future: scores of companies now use VR as a way to showcase their products and experiences.

But in the fifties, corporations just weren't ready, and the Sensorama failed to secure sufficient investment or sales.

An alternate route to riches was to use it as an arcade machine. A coin-operated unit was installed at Universal Studios "and was making tonnes of money with the quarters people were pumping into it," Marianne recalls, "but the management at Universal Studios at the time thought it was too much for a family company, so we had to take it out and put it on piers. It was on Santa Monica pier, in Times Square, and all over. It was a good little cash machine, I tell you that!"

But quarters weren't enough to sustain an invention that had cost a fortune to produce, and so Heilig sought investors. He arranged to meet in California with one interested party, introduced to him by "a guy who owned half of San Francisco at the time," Marianne comments, "but Mort was ten minutes late and the investor just left."

The powerful man who arranged the meeting did eventually put money in himself, but "Mort just couldn't get it going" - the machine was made of many pieces he had created himself, and wasn't especially robust: when it was put into an arcade, it promptly broke.