OnLive, Google Stadia and the long road to a worthy game streaming service

A potted history of the future of gaming

The world of gaming is changing. No discs. No installs. No boxes. That’s the seemingly-revolutionary promise of Google Stadia, the search and phone giant’s game streaming play for the hearts and minds of gamers. But, in spite of its apparent game-changing technological advances, Stadia as a concept has existed long before Google ever showed an interest in the space.

Game streaming is an area of gaming filled with lofty promises and missed expectations, but built on genuinely exciting principles. Google’s Stadia, revealed at GDC 2019, appears set to right the wrongs of many of its predecessors. But for Google and its heir apparent platform to manage that, the company will first have to have understood where its new platform's ancestors fell.

- First look: Stadia controller

- Hands on: Google Stadia review

- Why Google Stadia could spell trouble for the PS5 and Xbox Two

OnLive: the gaming giant that could have been

Readers of a certain vintage can cast their minds back 10 years to a very different GDC. Batman: Arkham Asylum and Call of Duty Modern Warfare 2 were the must-play games of the year, and the Nintendo Wii was still a marvel with its motion controls. But the games industry was about to get a surprise that would only begin to resonate nearly a decade later: the reveal of OnLive.

Despite the limitations of broadband connectivity at the time, OnLive, somewhat magically, actually worked.

OnLive was a cloud gaming service that used remote servers to render AAA games, beaming playable video streams back to gamers in their homes without the need of expensive consoles or PCs. If that sounds familiar, it’s because it's the exact same principle that Google Stadia is built upon.

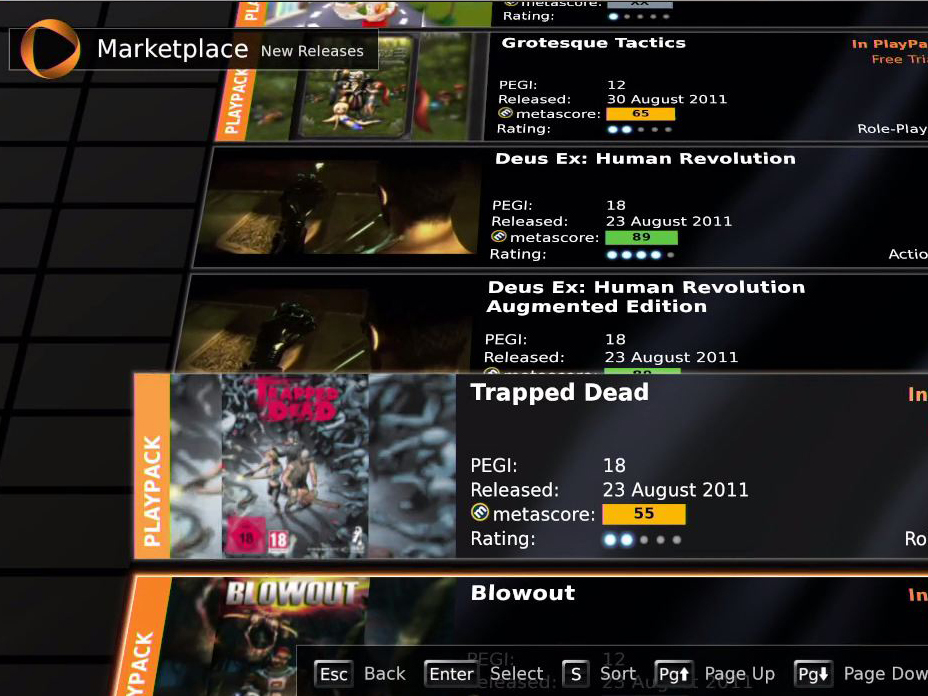

With servers around the globe, OnLive offered a reasonable catalogue of games to users for either a one-off fee or (eventually) as part of a per-month subscription package.

Despite the limitations of broadband connectivity at the time, OnLive – somewhat magically – actually worked. Users could log into the service via either a desktop client, mobile app or inexpensive microconsole (complete with unique control pad) and be presented with a 720p stream of AAA titles, including the aforementioned Arkham Asylum.

Input lag and latency were indeed present, and fluctuated dependent on a user’s distance from the OnLive servers as well as the quality and consistency of their broadband connection. But it was, for many of those that took the plunge with OnLive, an acceptable experience – one that would even introduce now-standard features of the gaming community beyond just game streaming, like the ability to broadcast and spectate other users’ play-in-progress.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Some analysts stated that OnLive at its height was worth as much as $1.8 billion (a sum primarily based around the technology OnLive was built on rather than its userbase, which was never really established or maintained beyond an early, short-lived spike in interest). The service eventually sold for just $4.8 million.

So what went wrong? Why did it never grow a substantial playerbase? Reports of mismanagement were rife. CEO Steve Perlman was by all accounts a genius, having previously created QuickTime and WebTV. But he failed to secure a growing catalogue of games to entice users, and apparently had fits of rage that resulted in partnerships being pulled when he found out developers were cutting deals with his rivals.

From a technical standpoint, too, the world simply wasn’t ready for OnLive. The average broadband connection in OnLive’s key markets didn’t have the consistent speeds required for a smooth experience at all times, and input lag prevented players from enjoying high-speed action games.

Gaikai and the roots of PlayStation Now

OnLive would be completely defunct by April 2015, with Sony picking up its patents. Previously in 2012, Sony had also acquired Gaikai, OnLive’s key rival, which lowered the barrier to entry with streaming games by offering streamed demos without requiring an online registration. Once a demo was complete, a player could then purchase the game in its entirety and continue playing. Websites could even embed the streams and take a cut of marketing revenue generated.

Gaikai would be the key to some of the most interesting aspects of Sony’s PlayStation 4 plans – elements that, in their own way, were important milestones for game streaming.

As with the PS3, gamers would be able to stream their gaming sessions to a Playstation Vita console over a home network, but with a far more enjoyable experience thanks to newer hardware and Gaikai’s technical knowhow.

More revolutionary was the concept of “Share Play”, using streaming tech to let a remote players join a ‘local co-op’ title over the web, as if they were in the same room together. You could even pass control of a single player game over to a remotely-located play using a streaming feed, letting them walk you through a difficult portion of a game.

Together, Gaikai and OnLive’s combined technologies would form the backbone of PlayStation Now, Sony’s own take on a game streaming subscription catalogue. Revealed at CES 2014, it was Sony’s workaround for supporting games on the previous generations of consoles, as the PS4 did not support backwards compatibility.

It also offered a PC client – a way to play otherwise-exclusive PS4 titles like Bloodborne on a computer. Somewhere in the region of 600 games are now playable for a monthly fee in this way, with PS4 games having now eventually made their way to the service too.

However, whether in response to Microsoft’s competitive Xbox Games Pass download subscription service or an admission that PlayStation Now’s streams also suffered from latency and streaming quality problems, PlayStation Now would also eventually add download options for select titles, which was a certified way to ensure smooth (if not instantaneously-accessible) play.

Current rivals and future hopefuls

Other household names of gaming have made similar attempts to make gaming more accessible through streaming.

Steam offered its In-Home Streaming service to gamers, letting them beam the video from their core, high end PC, to any other lower-powered PC (or Steam Link accessory) in another room. In effect, you could bring that high-end PC gaming experience to your living room over a low-powered laptop without having to move your huge rig around the house. Its latest evolution is Steam Link Anywhere, which brings mobile play into the mix.

Google may be an innovator with Stadia then, but it’s far from being an originator.

Nvidia's GRID system, introduced in 2008, is specifically designed to support cloud gaming systems. It would eventually become the backbone of its GeForce Now service, which has offered multiple services, from using a home computer to straem to a cloud-based subscription service to its latest iteration, which offers users access to a remote virtual computer from which to rent and stream a huge variety of PC games.

If Steam, Nvidia and PlayStation are Stadia’s existing competition beyond the console space, what’s awaiting it in the wings? Microsoft’s nascent Project xCloud.

It will leverage Microsoft’s Azure cloud data centers and the Xbox back catalogue to bring cloud-streamed games to any device with a screen – including mobile devices, where Microsoft is working to develop an unobtrusive touchscreen interface for playing on the go when a Bluetooth controller isn’t handy. There’s no word on an official service yet using Project xCloud, with it remaining very much in development. But don’t be surprised if it proves to be a large part of the Xbox Two experience.

Ultimately, Google may be an innovator with Stadia, but it’s far from an originator. Game streaming’s history is long and storied, and Stadia’s competition already exists, with services that are already breaking down the traditional concepts of console and game ownership. Google Stadia appears to be making all the right moves for its service to be a success, but it faces all the same challenges that have plagued its predecessors: it must have a strong game library; it must minimise input lag; it must be capable of delivering an enjoyable experience across middling broadband connections. And only some of those challenges are within Google’s power to influence or control.

Gerald is Editor-in-Chief of Shortlist.com. Previously he was the Executive Editor for TechRadar, taking care of the site's home cinema, gaming, smart home, entertainment and audio output. He loves gaming, but don't expect him to play with you unless your console is hooked up to a 4K HDR screen and a 7.1 surround system. Before TechRadar, Gerald was Editor of Gizmodo UK. He was also the EIC of iMore.com, and is the author of 'Get Technology: Upgrade Your Future', published by Aurum Press.