Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Let's face it, wires are for losers. All the cool kids are down Starbucks with their Macs updating their MySpace pages, while slurping a decaf fat-free mocha choca latté with extra sprinkles, just to make sure you had to wait in line for as long as possible. Little does the loafing wireless user know, but making that connection is a vast array of complex protocols and signaling technology.

If you look into the 802.11 standard it's a hideous mish-mash of compromises, that if anything has only just been sorted out with the ratification Wireless-N. Why do we say that?

Take 802.11a, this ran at 5GHz and used a modulation system called OFDM (Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiplexing). The preferred frequency range is 5GHz, but back in 1997 this was only available in the US and Japan. The compromise was that the rest of the world used 2.4GHz for 802.11b.

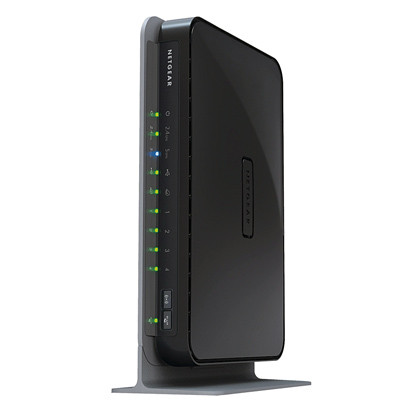

WI-FI ROUTER: Switching to 5GHz band can mean you can transmit twice as much data each time

The problem is this is a horribly noisy band competing with microwaves, DEC phones, Bluetooth and military 'airborne devices'. So it had to use a less-efficient modulation system, one called CCK (Complimentary Code Keying) for 2Mbps and 1Mbps speed and DSSS for 5.5Mbps and 11Mbps speeds.

802.11g upped speeds to 54Mbps by using the OFDM system, but this slaughters the maximum usable distance offering no improvements over 'B'.

To muddy the water even more a raft of manufacturers jumped on the 'turbo G' bandwagon. This makeshift standard used a number of techniques to improve the speed and distance of communication over standard 'G'.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The first from Atheros dubbed 'Super-G' and RangeMAX used channel-bonding. As the name suggests this makes use of two channels to broadcast data, doubling throughput to 108Mbps, but at the expense of potentially interfering with other wireless devices. Broadcom released a competing standard with a claimed throughput of 125Mbps that used a combination of aggressive compression and frame-bursting to boost bandwidth over a single channel.

The final crowning glory was the introduction of MIMO. At its simplest MIMO uses multiple data or spatial streams to transmit more data in one go and with better reliability via multiple antennas.

With the ridiculously elongated ratification process of 'N' the industry released its own MIMO-G options, then Pre-N kit, then Draft-1 N, Draft-2 N and now the dual-band capable 2.4/5GHz 'N' products. Thankfully, Draft-2 products are highly mature and the speed they're capable of is impressive.

WIRELESS GADGETS: You might have some trouble connecting this up with Ethernet cable so you might want to consider going wireless

The idealistic 300Mbps throughput is entirely fantastical – devised only in a laboratory – but we did record peaks as high as 17MB/s in a same room scenario and average transfers of 14MB/s are entirely possible. For day-to-day performance expect around the 8-10MB/s mark.