What makes horror games so scary?

The horror game tricks and levels that fill players with fear

With familiarity the enemy of horror, it's no wonder that most of the scares that stick in our minds for years and years aren't actually entire games, but slices of other, non-horror titles. Thief for instance is an incredibly tense game, built around hiding in the shadows, being weak and vulnerable and playing incredibly carefully, but not horror.

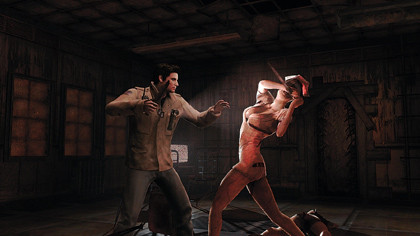

ALONE IN THE DARK: Master of the 'it's behind/above/anywhere around you' ooga-booga scare

The two levels that everyone remembers, however, are the ones where the darkness wraps around like Garrett's fine cloak: the Haunted Cathedral in the first game, and The Cradle in the third. The Cradle (created by Bioshock 2 head honcho, Jordan Thomas) is a mix of asylum and orphanage, as dark and spooky as any such place can be in the night, but also richly layered with history.

These aren't empty rooms. As you pick through, you slowly piece together what actually happened in this place; the dry heat brands used to try to burn out madness, the mutilated pictures, the ghosts trapped by the cold stone and tortured memories. It's the horror of dread, not fear, all the more effective for knowing that it's not that far off reality. The fact that it exists as a fictional space quickly ceases to matter.

The Ocean House from Vampire: Bloodlines pulls a similar trick. This one is all the more interesting because for the rest of the game, you're firmly cast in the role of predator: an unfeasibly tough vampire capable of going toe-to-toe with almost anything short of a werewolf, in a gameworld built on letting you enjoy that thrill.

Being haunted by ghosts – which you're explicitly told are beneath your notice – is a one-time experience, as you find yourself in rooms that explode into fire, with floors collapsing under your feet, spooky noises catching your attention, objects flying across the room. Nothing that happens is, in itself, that scary, but the first time through, it's an absolutely chilling experience, and one that sets up the idea that no matter how tough you think you are, there's always going to be something that can give you a shock.

Some of the scariest moments in games, though, come when you're not expecting them at all. Lands of Lore 2, for instance, is a fairly light-hearted RPG, which suddenly drops you into a ghost-filled series of caves with spooky voices taunting you.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Ultima VII was one of the first games to let the villain speak to you directly, suddenly breaking into laughter or screaming out of the speakers as you explored the land of Britannia.

Even Monkey Island 2, a comedy game, gets into the act. After a whole game set in a light-hearted, if supernatural-spiced Caribbean, the final act takes place in nothing short of a lost child's nightmare, with the villain bursting in at random intervals to torture the hero with a voodoo doll. These moments, unexpected but beautifully handled, are nothing short of a sucker punch, and all the more memorable for it.

Dreams of Silent Hill

Most dedicated horror games are typically referred to as 'survival horror' – action games, with more emphasis on dark locations, mazes, limited ammunition and jump-scares. Some of the most famous include the thirdperson adventures Resident Evil and Alone In The Dark, and more recently, Dead Space.

They tend to be third-person to make better use of cinematography, but this isn't mandatory. The real split comes from how capable the player is of fighting against the enemies; how much focus there is on survival instead of conquering the baddies.

As such, Left 4 Dead counts, but FEAR and Doom 3 not so much. Much of the genre comes to us from Japan, so it's no surprise that they tend to get fairly strange. Western games can be just as bizarre, though, and they don't get much more so than Alone In The Dark.

The opening sequence of this was one of the most iconic gaming experiences of the early 1990s: your character in the attic of a big spooky house, trying to close off the window and trapdoor and other entrances before any slathering monsters could break in. As you explored, you found a hideous HP Lovecraft-inspired secret beneath the house, unkillable monsters, copies of books like the Necromnicon in the library, and the secret horror hidden away in the basement.

The sequel… had you dress up as Santa to sneak past zombie pirates. Because it was Christmas and they were having a party. Yes. After that, things really got silly.

Alone in the Dark and the early Resident Evil games had a lot in common. They had a locked down setting, third-person exploration, and roughly the same idea of how to scare the player: lots of enemies jumping in through windows, off-putting camera angles, and main characters whose combat ability was mostly hampered by truly horrific controls.

In both cases, the ooga-booga scares were kept fresh by the fact that (first time through, at least) you had no idea what was going to happen. Enemies could come from anywhere. Anything could be a threat. Every door was there to build tension between rooms. Both of these games were soon replaced however by the Silent Hill series.

Silent Hill has its ooga-booga scares as well, but they're not the focus. Instead, they're primarily psychological horror, set in a small town that forces unlucky visitors to its foggy streets to literally face their demons; crafting Hell out of their personality flaws and biggest regrets.

SILENT HILL: Working the psychological horror gig since 1999

Unlike many survival horror games, we're not really meant to see ourselves as them, but rather peel away the layers to find out why they deserve their fate, and possibly help them find some peace as a result. As games, they're definitely flawed in many ways – you spent a lot of time just jiggling handles to find out where to go, for instance – but as pieces of horror, they're exceptional.

Everything from the haunting vocal tracks (look up 'Room Of Angel' online) to the foggy streets and bursts of static on the radios that let you know when trouble is coming…

Of the series, Silent Hill 2 is the only true must-play. The controls are terrible, and the later games progressively lose the plot, but all of them (aside from the latest, Homecoming, which is crap) share a knack for truly fantastic moments that will stick with you far longer than you'll ever want. In a good way. They demonstrate every single way of generating fear, and not many games do it better.

Fear and loathing

As with Hollywood, it's the lingering horror that marks out most of the best horror games: the backstories that make you wince, not the monsters. Cheap scares are exactly that. Scaly monsters have little power in and of themselves, not when we routinely blast our way through thousands of them in the course of a single game.

But an idea – that lingering dread – is something that transcends graphics and genre, something that stays effective long after a game has been consigned to the bottom of the pile. In a few rare cases, the effect remains so good, it's still effective even when the technology is obsolete or the market has moved on.

The importance of fear stretches beyond simply enjoyment though. We can sympathise with fictional characters, we can enjoy the experience of being awesome, but fear is the only emotion that truly puts us in their shoes; that lets us share that reluctance to go down the dark corridor, that makes us directly connect with the action on the screen. It's a pure emotion, a visceral reaction, one that goes right to our souls.

By beating it, we do more than beat the game; we achieve something, and it's all the more satisfying for not simply being a test of motor skills or cold, detached tactics. Done properly, fear is the ultimate spice. But if developers can please knock it off with the bloody spiders, that'd be nice.