Disney Plus’ new documentary will make you see Star Wars (and other blockbusters) in a whole new light

Light & Magic shines a light on the VFX geniuses of ILM – and it's utterly glorious

You probably remember a scene that transformed your idea of what was possible on the big screen, a moment that went so big on the wows that you simply had to shout about it – or at the very least, book another ticket to the theater to see it a second time.

Depending on when you were born, it could have been that Star Destroyer filling the frame in the opening seconds of the original Star Wars, the T-1000 seamlessly morphing into liquid metal in Terminator 2: Judgment Day, or photorealistic velociraptors going on the hunt in Jurassic Park.

All of these moments were imagined by visionary directors with an appetite for pushing the cinematic envelope, but George Lucas, James Cameron and Steven Spielberg were also standing on the shoulders of giants. Without the groundbreaking efforts of the visual effects pioneers at Industrial Light & Magic, their ideas would have remained mere words on a page – to paraphrase Harrison Ford, you could type that s**t, but until ILM came along, you sure as hell couldn’t make it happen.

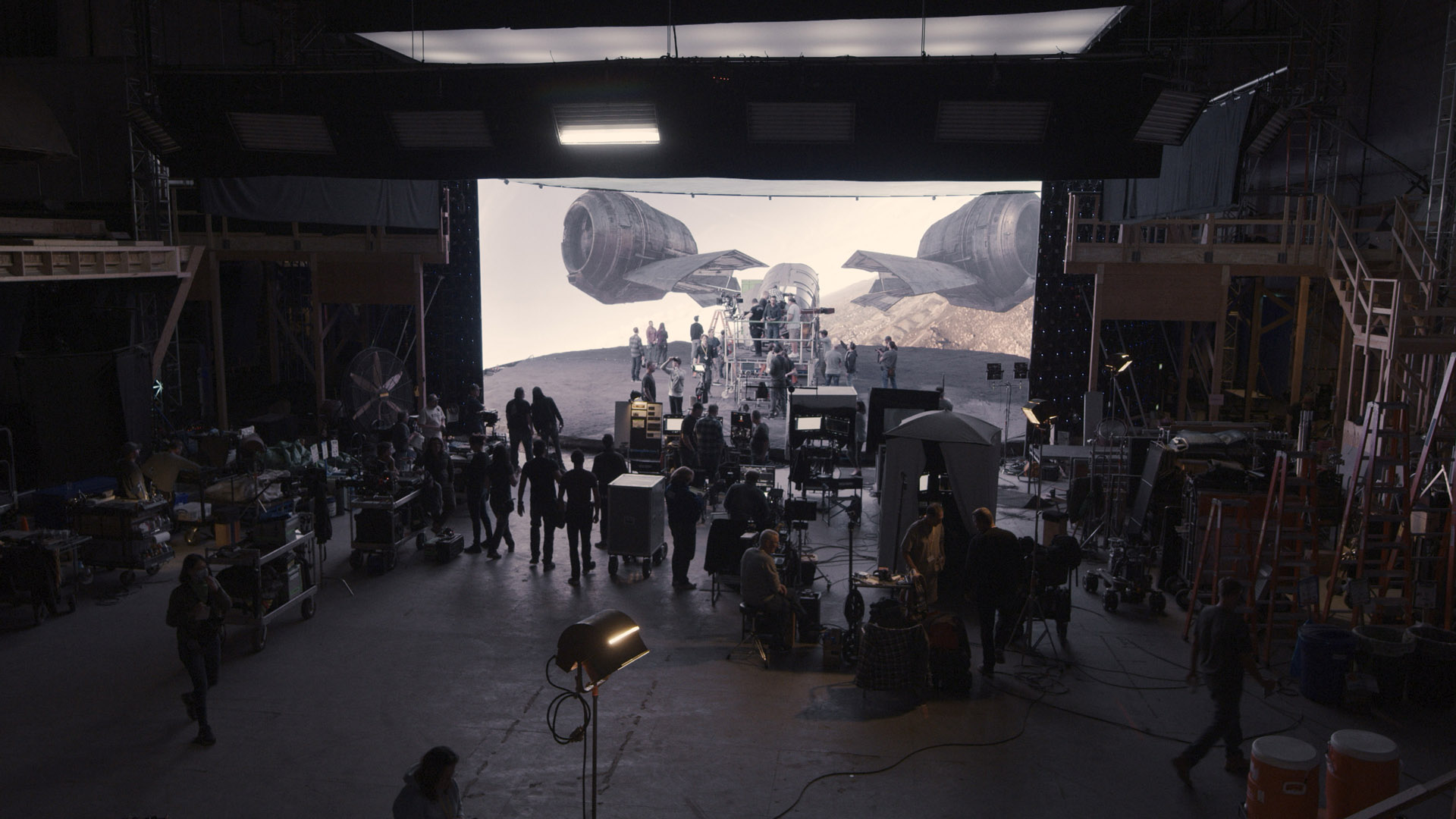

New Disney Plus series Light & Magic shines a light on pioneers who’ve consistently supplied the 99% perspiration that can turn a screenwriter’s 1% inspiration into jaw-dropping visuals. As the documentary charts the journey of Hollywood’s most famous purveyors of movie effects from the mid-’70s through to the CG-dominated present day, this joyous, awe-inspiring peek behind the filmmaking curtain helps you see your favorite blockbusters in a whole new way.

As numerous ILM geniuses (and we don’t use the word lightly) look back on glorious careers that have turned making the impossible possible into an artform, it becomes clear that the “magic” part of the company’s name is no exaggeration. Indeed, while keeping the mechanics of an illusion under wraps is traditionally part of the magician’s trade, looking behind the scenes at ILM only serves to make those iconic movie moments more special. This is where art, science and talent collide – and the results have a habit of being spectacular.

Illusions of grandeur

ILM was created because the interstellar action George Lucas had envisioned for Star Wars wasn’t possible with mid-1970s technology. Many of the major Hollywood studios had closed their visual effects departments, and while 2001: A Space Odyssey had delivered memorable space scenes in 1968, its stately, silent approach was light years away from the high-speed dogfights Lucas had in mind for X-wings and TIE Fighters. Lucas’s solution to the problem changed cinema forever, as he decided to establish a new company capable of turning his dreams into reality. That company was Industrial Light and Magic.

The director’s first port of call was Douglas Trumbull, the VFX pioneer who’d worked with Stanley Kubrick on 2001, and would go on to work spaceship magic on Close Encounters Of The Third Kind and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. But when Trumbull was unavailable, he pointed Lucas in the direction of a young protégé by the name of John Dykstra.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Although relations between Dykstra and Lucas would become strained through the making of A New Hope – with pre-release deadlines looming like an angry Star Destroyer, Lucas became exasperated with the amount of time the nascent ILM was taking to deliver finished effects shots – they were a match made in creative heaven. Armed with groundbreaking ideas about shooting spaceships with digital motion control cameras – his Dykstraflex system helped us believe a Millennium Falcon could fly – Dykstra gave his boss’s big ideas tangible, cinematic form. But arguably more importantly, he persuaded the likes of Dennis Muren, Richard Edlund, Joe Johnston, Phil Tippett and Ken Ralston to join him on Lucas’s damned fool idealistic crusade.

Although they’ve since gone on to become legends in the VFX community – picking up Oscars and stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame along the way – they were an unlikely bunch of recruits. Some of them had worked in advertising, others had attempted to emulate Ray Harryhausen in ingenious home movies, but while most of them lacked genuine big screen experience, that paled into insignificance next to their passion, ingenuity, and refusal to believe that anything – well, pretty much anything – was impossible. Watching them in Light & Magic, looking back as talking heads – or immortalised in an impressive collection of archive footage – is utterly, upliftingly infectious.

Sure, at times they look like students given the keys to the world’s greatest toy shop – Lucas compares the atmosphere at ILM’s original warehouse HQ in Van Nuys, California, to a “fraternity house” – but if this was a school, they’d be picking up straight As.

The craftsmanship of the spaceship models or background matte paintings is undoubtedly second to none, but it’s the seat-of-the-pants inventiveness that makes them really special. In those pre-computer graphics days, their solutions for getting the Falcon to jump into hyperspace, or – after Lucas opened ILM’s doors to his filmmaker buddies – making a house implode in Poltergeist, have a wonderfully MacGyver-ish quality. As glorious as modern CG can be, old-school analogue techniques involving optical printers, model-making kits, and stop-motion animated AT-ATs are so much more romantic than watching someone move pixels around with a mouse.

The digital age

Despite its affection for old-school filmmaking, however, Light & Magic also gives ILM’s pioneering moves into the digital world their due. Lucas himself emerges as something of a visionary, not just for forming the company in the first place, but also for identifying the ways computers could – and subsequently did – transform Hollywood.

ILM and Lucasfilm’s journey from the Genesis planet simulation in Star Trek: The Wrath Of Khan to the point where convincing dinosaurs could be created on a computer desktop – via The Abyss and Terminator 2 – is arguably as remarkable as anything Dykstra and his team pioneered on Star Wars. But it’s also tinged with an undeniable sadness, as effects legends who’d reached the absolute pinnacle of their trade in an analogue world either had to adapt to the new world order, or be left behind.

Now that pretty much anything a writer can imagine can be visualised on screen if you have enough time and money, few would argue that a return to the techniques that established ILM as a powerhouse would be financially or artistically viable. But Light & Magic shows how the likes of Dykstra, Muren, Edlund, Johnston, Tippett and Ralston were arguably just as important to Star Wars’ success as Harrison Ford, Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher – and celebrates them as the Hollywood legends they undoubtedly are.

After it ushered in a new era of big-budget blockbusters, Star Wars was often blamed by critics for kickstarting the dumbing-down of cinema. Light & Magic shows that the opposite was actually true, and that thanks to the work of ILM, a new form of storytelling – one unique to the screen – was born. Everyone has their favorite movie quotes, but most will also have their favorite Industrial Light & Magic effect too.

Light & Magic is available to stream now on Disney Plus.

Richard is a freelance journalist specialising in movies and TV, primarily of the sci-fi and fantasy variety. An early encounter with a certain galaxy far, far away started a lifelong love affair with outer space, and these days Richard's happiest geeking out about Star Wars, Star Trek, Marvel and other long-running pop culture franchises. In a previous life he was editor of legendary sci-fi and fantasy magazine SFX, where he got to interview many of the biggest names in the business – though he'll always have a soft spot for Jeff Goldblum who (somewhat bizarrely) thought Richard's name was Winter.