From parts to product: how a Windows 10 device is born

The Pyramid Flipper developers tell all

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Raising the barn

When both the designers and engineers finally reach a consensus, the company begins work on tooling, or creating the mold of the actual product, which includes the casing, the housing, the appearance of the device.

For this stage, Eve-Tech partnered with an Asian machining company named CNC Machining China. Using nothing more than part drawings and "detailed requirements" sent by email or fax, the tooling factory took a block of a material (usually plastic or aluminum) and cut it to shape using robotic machines.

"One piece is carved and then you get a finished product out of it, it's a little bit like a 3D printer. That's actually what Apple does for their products," Karatsevidis tells us.

A cheaper option, he says, would be die casting, where you take a sizable steel form and pour hot metal inside of it, resulting in the ejection of a ready-made enclosure.

After this stage comes the electrical engineering aspect to create an actual working device. For this, you'll need to first acquire a reference design or basically a blueprint layout of the motherboard. , a high-level layout of the motherboard, originating from Intel and passed on to the supplier. Karatsevidis says that you can expect a reference design from any chipset supplier such as Intel, but getting the motherboard ready after that is where things get tricky.

The manufacturer itself, in this case Eve-Tech, has to take the motherboard reference map then tweak it to match what the customer wants or, in the case of more prominent hardware creators, what the retailer demands. On a very high level, this involves trimming the motherboard and seeing if you can "squeeze" it into the product design.

Once the motherboard has been tailored to the device, the next stage is mass production, which comprises another subset of stages called EVT (engineering validation testing), DVT (design verification testing), and PVT (production validation testing).

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

EVT, Karatsevidis told us, tests what is essentially a working prototype, less the final casing design. It's a barebone mockup featuring nothing more than a motherboard and all of the internal components attached. Likewise, DVT tests the design and PVT makes sure the device is ready for mass production.

The final step in manufacturing is a pivotal one. It's finding a factory that will actually produce the product in the thousands.

"What you do is you take the project, and you get networked with them somehow because the email addresses on their websites just don't work," Karatsevidis said. "And then you come and you try to pitch your project to them. After you pitch it, they're either ready to do it or not."

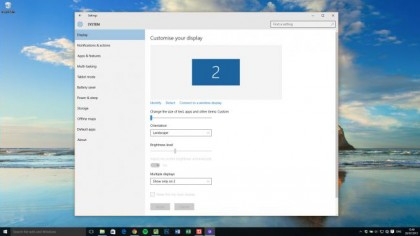

Software licensing

You might think going through Microsoft to get approved for Windows 10 licenses across half a million tablets would serve as an arduous barrier standing in the way of shipping a final product. But, according to Eve-Tech, it was the least threatening process.

"It's actually very easy," Karatsevidis told us. "You just tell [Microsoft] you need licenses, and then after that you're free to buy as many licenses as you want."

With the executive members of the company based in Finland, home of Microsoft's corporate mobile-centric offices, the only thing in the way of getting licenses was a 10 minute drive.

After working out a deal with Microsoft, Eve-Tech received special license keys to accommodate each of its devices.

Karatsevidis points out one more interesting factor in regards to software licensing, though, and that's bloatware – a subject that most PC users find annoying. Although the Pyramid Flipper will ship with the stock version of Windows 10 pre-installed, some PC makers are infamous for shoehorning in extra programs that you most likely didn't need or ask for.

"At our company, the idea is that we have Windows 10 with no bloatware, and this idea is something that big companies don't do," he told us. "They sell you laptops with pre-installed software there – they usually call it a free software package or something. Why you have it, I don't know if you've ever wondered, but to some people it's a surprise."

In many cases, the bloatware is disguised as anti-virus or some kind of third-party computer "aid" that expires after a trial period. The more lucrative manufacturers, like Dell or HP, will typically get between 30% and 50% commission if the customer decides to buy the software when the trial is over.

Markups on markups on markups

Finally, marketing is an ongoing procedure that often costs so much that it causes the manufacturer to ramp up the price on the hardware two or three times what it took to actually build it. We're looking at you Apple.

Karatsevidis reveals a considerable series of markup costs can be cut by reducing marketing expenses, eliminating retailers and instead of selling directly from manufacturer.

In between each of these is about a 5 to 15 percent markup on top of the product cost in addition to marketing costs. As a result, it's common that products are designed entirely with the retailer in mind rather than the consumer, which leads to what Karatsevidis considers shoddy products.

"Customers want something else, but retailers, they are the ones who actually tell the manufacturers what they should build, and that really leads to terrible things, like really bad designs on the market because no retailer would want to give up their clean margins," he said.

In the end, it appears that what it really takes to make a Windows 10 device is a strong sense of what the end-buyer wants, whether that's the retailer, the consumer, or in Eve's case, the people stampeding over tablet specs in the comments sections of articles like this.

- Find more inside stories on our behind the design series