Inside the Project Blue mission to photograph 'sister Earth 2.0'

A new era of planet hunting

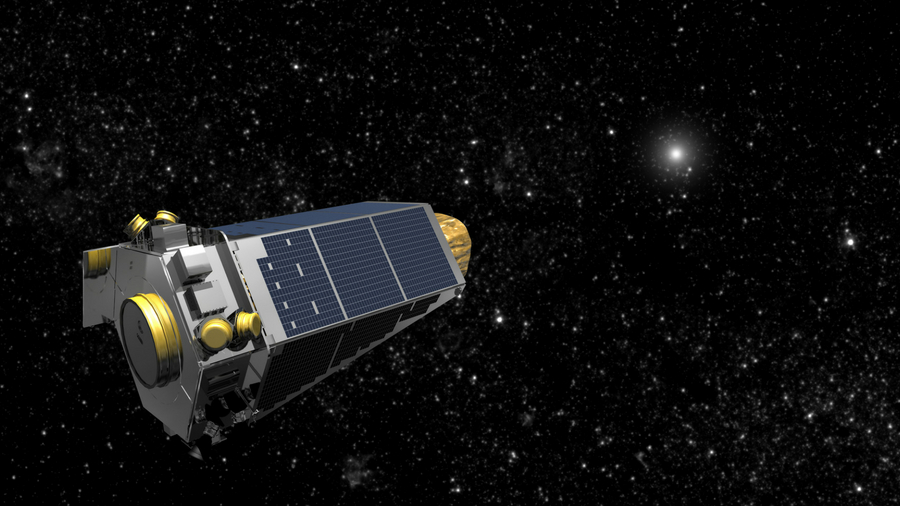

Main image: Data from the Kepler space telescope has been used to find thousands of exoplanets. Credit: NASA

It would be the greatest scientific find in history.

Countless alien worlds have been discovered in recent years – in fact, from a single example in 1992 there are now 3,730 confirmed exoplanets – defined as a planet that orbits another star – on the list. NASA has even launched its Exoplanet Travel Bureau, which explores three of the most Earth-like: Kepler-16b, Kepler-186f, and TRAPPIST-1e.

However, not a single exoplanet has ever been photographed.

Cue Project Blue, which aims to build and launch a space telescope that can image planets situated in the 'habitable zones' of stars in the Alpha Centauri system, the star system closest to us. A habitable zone around a star is the range of orbits far enough away for a planet to support liquid water, which scientists think is a must-have for life to evolve.

If any exoplanet has an atmosphere, or an ocean, this special telescope could photograph them… and could confirm the existence of another Blue Planet similar to our own, which may contain life.

- Do you have a brilliant idea for the next great tech innovation? Enter our Tech Innovation for the Future competition and you could win up to £10,000!

What is Project Blue?

Project Blue is about taking the search for Earth 2.0 from observational astronomy into visual astronomy. While most exoplanets have been discovered using the 'transit' method (a telescope observing a star's light dim slightly as a planet travels across its disk), the future of exoplanet exploration is going to be all about direct observation and photography.

Conceptually, Project Blue is a plan to produce an image to rival two other iconic astronomical images – Apollo 8’s 1968 photo of the Earth-rise around the Moon, and Voyager 1’s ‘Pale Blue Dot’ image from 1990, which Carl Sagan described as showing Earth as ‘a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam’.

The crowdfunded Project Blue mission (you can donate here), which aims to blast off in the 2021, is the brainchild of the BoldlyGo Institute, Mission Centaur, extraterrestrial life-hunters the SETI Institute, and the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Which star system will Project Blue look at?

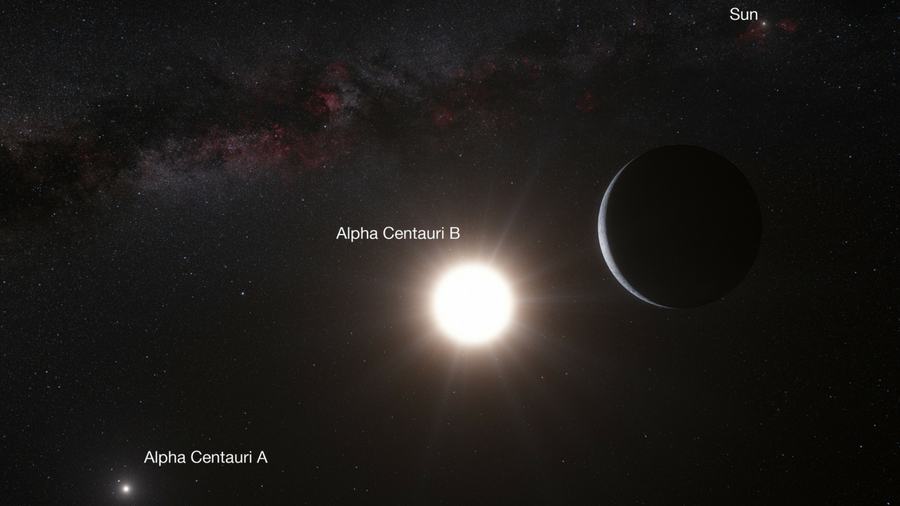

Alpha Centauri, the nearest star system to Earth. “It’s a special place to do exoplanet imaging,” says Dr Jon Morse, CEO and Chair of the Board, BoldlyGo Institute, speaking at the Dawn of Private Space Symposium in June. “It’s also the closest star system to us, by a factor of 2.5 closer than the next Sun-like stars that might have a solar system similar to ours.”

Alpha Centauri is no ordinary solar system. A mere 4.37 light years from us, it consists of three stars: two Sun-sized stars called Alpha Centauri A (also called Rigil Kent) and Alpha Centauri B, and the much smaller Proxima Centauri red dwarf star. In fact, Proxima Centauri is the nearest to us at just 4.24 light years, but despite an Earth-sized exoplanet called Proxima Centauri b being discovered in 2016, Project Blue will ignore it.

While it could be the closest exoplanet to us, there’s a simple reason why Proxima Centauri b is being ignored. “We’re not looking at Proxima Centauri because its habitable zones and the planet that we suspect is there are much too close to the star for us to spatially resolve it,” says Morse. “So we’re focusing on the Sun-like stars Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B.”

How big is Project Blue's telescope?

It's actually pretty small. "It's as large as it needs to be," says Morse. "Alpha Centauri is special because it’s only 4.37 light-years away, and we only need a 50cm diameter primary mirror in our telescope to spatially resolve the habitable zones."

From low-Earth orbit, this small space telescope will point at Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B, the two largest stars in the Alpha Centauri system, which are both the same size (give or take) as our Sun. Astronomers already know that Alpha Centauri B has a planet orbiting it, but it's not in the star’s habitable zone. So Project Blue will be on the lookout for new, as yet undiscovered – and, hopefully, blue – exoplanets.

A new era of exoplanet photography

If direct imaging of exoplanets is to be the future of astronomy, some foundational technologies need to be tested first, and that's exactly what Project Blue is intended to do. It will use a disk to block each star's bright surface – thus creating an artificial total solar eclipse – so it can see nearby planets.

But it will also use a technology called active wavefront control to detect very faint reflected starlight – something that even the US$8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope won’t be able to do. "JWST will have coronagraphs that scientists will use to image Jupiter-class planets around nearby stars, but the JWST coronagraphs won’t have active wavefront control, and so won’t be able to look as close to the stars as we intend to with Project Blue’s coronagraph," says Morse.

The only other mission currently planned to have a coronagraph to image exoplanets is NASA’s WFIRST mission, scheduled to launch around 2025. Future mission concepts that could photograph exoplanets decades from now include Starshade, EXO-C, HabEx and LUVOIR.

Where is Alpha Centauri in the night sky?

The two bright stars of Alpha Centauri appear as a single point of light in the night sky, and it’s mostly visible only from the southern hemisphere. It’s the brightest star in the southern constellation Centaurus the Centaur. In fact, Alpha Centauri and its visually close neighbor, Beta Centauri (which is a whopping 390 light-years from us), point to the Southern Cross.

However, those living below 25 degrees north of the Earth's equator (such as in Florida, North Africa, the UAE, Northern India and Southern China), do sometimes see Alpha Centauri peek above the southern horizon. That explains why this star was worshipped by the ancient Egyptians, who erected temples at Corinth and Delphi that align to the rising of Alpha Centauri.

How long would it take to travel to Alpha Centauri?

It may the closest star system to us, but using current rocket technology it would take about 30,000 years to cross the 40 trillion kilometres (or 4.37 light years, or 1.34 parsecs), between us and Alpha Centauri.

So if we could travel at a tenth of light speed, we could make the trip in about 44 years. Speculative projects include Breakthrough Starshot which would send 1,000 ultra-lightweight nanocraft traveling at a fifth of light speed, and propelling a tiny graphene-shielded spacecraft on the tip of a laser beam; it’s likely, though, that any mission we sent to Alpha Centauri would be overtaken by a mission launched much later but using newer, faster technology.

For the foreseeable future, however, interstellar travel is a slow process, and so the search for Earth 2.0 is likely to remain a purely photographic hunt for many decades to come.

TechRadar's Next Up series is brought to you in association with Honor

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),