How Apple became bigger than the Beatles

Apple's amazing rise to the top of the music industry

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Two years after Napster shut down, piracy was bigger than ever. The record labels were chasing Napster's spiritual successor Kazaa through the courts, but it was still going: at any given time between 1-5 million people were sharing more than 1.5 billion files, and that was just one of several file-sharing systems that appeared in Napster's wake.

MusicNet and PressPlay weren't making much of a dent because, as Paul Brindley puts it, "They came at it from the perspective of the majors trying to control the subscription business. They soon realised they were not very good at that, thankfully."

Mark Mulligan agrees, describing the legal services as: "A pitifully poor generation of products that actually accentuated the impact of disruption by making the legal alternatives [to file sharing] so poor that they were no alternative at all."

And then Apple released iTunes 4, which included its very own music store.

Everything MusicNet and PressPlay did wrong, the iTunes Store did right: instead of wildly varying pricing, every song was 99 cents. Instead of weird and inconsistent copy protection ("this track gives you one CD burn and three listens on a portable player, this track can't be burned at all, this track gives you six burns and 100 listens) iTunes tracks had FairPlay.

This meant you could use them on three (later, five) Macs, unlimited iPods and unlimited CDs – although you could only burn a playlist containing FairPlay tracks once).

Steve Jobs didn't want DRM at all. As he told Rolling Stone, "When we first went to talk to these record companies – you know, it was a while ago. It took us 18 months. And at first we said: none of this technology that you're talking about's going to work. We have PhD graduates here who know the stuff cold, and we don't believe it's possible to protect digital content."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The labels wouldn't budge, however, and despite Jobs' misgivings the iTunes Store launched with FairPlay-protected content. Critics accused Apple of operating a closed system, and that's true: it had the shop, the music software and the portable player.

"Closed systems can only work if they are used to protect a quality of experience, not to simply control," Mulligan says. "That's why Windows DRM-powered services failed and iTunes succeeded."

In less than three years Apple had 1 billion songs (the billionth was Coldplay's Speed of Sound) and four years later downloads cracked the 10-billion mark. As for PressPlay and MusicNet, the former was sold to Roxio, rebadged as Napster 2.0 and relaunched in 2003; MusicNet became MediaNet in 2007 and powers download shops from the likes of Yahoo, HMV and Zune.

ZUNE: Despite Microsoft's best efforts, the quite-impressive Zune HD isn't impressive enough to tempt people away from their iPods

Baby, you're a rich man

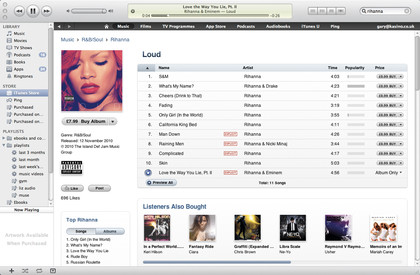

By 2007, Apple was the king of the music world. The iPod had 72.7% of the entire MP3 player market and 70% of the music download market. A 2007 study by Piper Jaffray found that among teenagers, iTunes had 90% share.

That market power meant Apple, not the music industry, was calling the shots – and that was largely the fault of the record labels. The DRM they insisted on wrapping their downloads in made Apple the most important player in digital music, because the only DRM that worked on iPods was FairPlay.

By effectively forcing every iPod owner to buy their songs from iTunes, the labels made Apple the only game in town. From 2003 to 2009, conversations between record labels and Apple went a bit like this: "Please can we put the prices up on iTunes? Please? Pretty please with sugar on top?" the labels would say. "Nope," Apple would respond.

As Steve Jobs told reporters in 2005, "If they want to raise the prices it just means they're getting a little greedy… Customers think the price is really good where it is." The standoff continued through 2007, when Steve Jobs wrote his Thoughts On Music essay (http://apple.com/hotnews/thoughtsonmusic) damning DRM and publicly urging labels to dump it.

EMI listened, enabling Apple to offer DRM-free songs under the iTunes Plus banner for a small extra charge, but other labels were stubborn. If they wouldn't do what Apple wanted, Apple wouldn't do what they wanted – so iTunes' price remained set at 99 cents and DRM remained on most iTunes tracks.

Unlike the labels, Apple doesn't depend on selling music for its income. It could sell every track at a loss and still rake in millions from iPod sales. The labels pushed for higher prices and Apple resisted – and the more songs it sold, the more powerful it became and the less leverage the labels had.

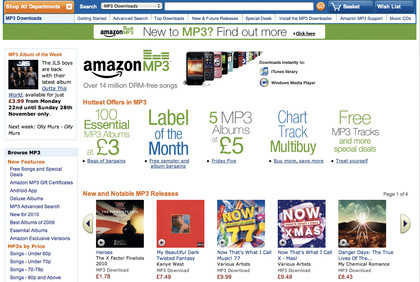

COMPETITION: Amazon's MP3 store doesn't appear to be taking market share from iTunes

Frustrated, some labels decided it was time to teach Apple a lesson: they would work with Amazon and help it launch an iTunes rival. The Amazon MP3 store launched in 2007 and offered DRM-free music, but it barely dented Apple sales.

Even today Amazon is far behind iTunes, with NPD Group reporting that Amazon has 12% of the music download market compared to iTunes' 70%. Amazon's share is growing, but not at Apple's expense: iTunes is up 1% since last year, with Amazon growing at the expense of Rhapsody, Napster and Microsoft's Zune.

Apple finally relented on pricing in 2009, but the labels had to dump the DRM to get it. Now, all iTunes music is sold DRM-free. Apple has long passed the point where it needs DRM to keep people shopping in iTunes.

Beatles for sale

The same Beatles deal that got Apple so excited could be getting other people excited too: antitrust regulators. While it's not illegal to have a monopoly in the US, it is illegal to throw your weight around to unfairly exclude your competitors. And with iTunes exclusives, it's arguable that Apple is engaging in anticompetitive behaviour because that music isn't available anywhere else.

That's not a big deal when it's the occasional Ellie Goulding or Rihanna bonus track, but when it's everything recorded by the most important band in history you can see why some might be concerned.

BONUS: One man's bonus track is another's anti-competitive behaviour. Critics say iTunes exclusive are unfair to the market

Every little thing

A lot depends on how you define the market Apple is in. If it's all music, then Apple's sub-30% share of US music sales means it's a big player, but hardly monopolistic. But if you only count downloads, then depending on whom you ask, Apple has between 70% and 90% of the market. When Microsoft had that much of the web browser market, regulators pounced.

"Apple is clearly too powerful," Mark Mulligan says. "Any market that has one company controlling 75% plus is not healthy." It's a view echoed by Columbia Law School professor and copyright expert Tim Wu: "Take a monopoly in several markets, mix it with an ideology of exclusion and it's easy to predict antitrust problems."

Wu points out that to regulators, iTunes' refusal to support other firms' MP3 players (and the upgrades that stop firms such as Palm from syncing their devices with Apple's software) look very like the kinds of behaviour that got Microsoft into trouble in the 1990s.

Mark Mulligan's concern isn't that Apple is taking an anti-competitive stance; it's that Apple's losing its long-held interest in music. "Steve Jobs' passion for music has undoubtedly been one of Apple's biggest assets," he says, but points out that Jobs' focus has moved to iPhones and iPads.

"Up until nine months ago iPods were still selling at record rates, so new iTunes customers were arriving at a sufficient rate to keep the digital market growing solidly," he says.

"Apple has taken its foot off the music product innovation pedal. Of course it has something up its sleeve, but it won't have the same priority a new-music offering would have had three years ago. As Apple dominates digital revenues, if music is less of a priority then the entire market feels the effect."

Apple has become so big in music that when it sneezes, the entire music business catches a cold – and there's no sign of a serious competitor on the horizon. "If Apple faced any serious competitive threat as a music provider they'd respond," Mulligan says. "They don't yet." The most likely competitor is Spotify.

At the time of writing, its long-awaited US launch has been delayed yet again, reportedly because it can't come to an agreement with the major record labels, and its UK operation is losing money.

"Their business model has so many questions over it Apple probably thinks it's wise to let Spotify burn through its investment," Mulligan says. "Then it could be bought by a large media or technology company that will, within a couple of years, sap the momentum out of it – as happened with MySpace, Bebo and Last.fm. Apple's crown isn't in danger yet."

Contributor

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than twenty books. Her latest, a love letter to music titled Small Town Joy, is on sale now. She is the singer in spectacularly obscure Glaswegian rock band Unquiet Mind.