Does Kinect herald the demise of the keyboard?

Kinect for Windows would give us a new way to control our PCs

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Do you know TED? Not the guy called Edward who lives next door, the Technology, Entertainment, Design conference.

It's a series of lectures for invited politicians, academics and commercial developers to tell the world about their best ideas, then cruelly limits their talks to 18 minutes so they don't get boring.

Attendance at the events is both exclusive and expensive, costing over $5,000 a ticket. The TED website is more democratic and puts up videos of the best of these intellectual elevator pitches under the banner: 'Ideas worth spreading'.

Subjects cover everything from tackling global poverty to nanotech to Wikileaks.org. If you're at all interested in what the PC of the future might look like, the conference has also featured talks about micro-projection, virtual keyboards and changing trends in Human Computer Interaction (HCI).

It's particularly well worth digging out information about two talks that showcased at this summer's TED Global conference in Oxford.

First up, Microsoft's Peter Molyneux took to the stage to demonstrate his forthcoming Xbox 360 game: Milo. Milo is a small boy who is significant in two ways. Firstly, he's the latest iteration of the learning AI technology that has been central to Molyneux' work since Black & White. Milo can be taught to clean up his room or crush snails, depending on your proclivity.

It's a two way interaction though: he feeds back his thoughts about such actions to you with the kind of emotional depth that makes Kevin Spacey's robot Gertie from the film Moon seem callous and cold hearted. Milo learns from the movements and gestures picked up by Kinect, Microsoft's 3D sensor array that's coming to the Xbox on 4 November.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

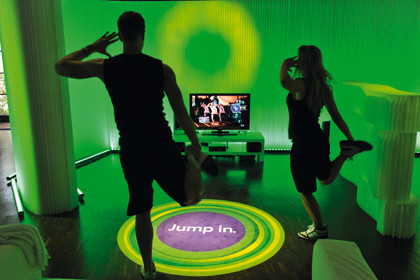

KINECT: Kinect needs to have sophisticated detection technology to accurately pick up your stupid dance moves

Kinect was first announced under the codename Project Natal just over a year ago, in June 2009. Kinect can track body movements from roundhouse kicks down to facial expressions and turn them into a control system for the games console.

In many TED Global reports, though, Molyneux' talk was eclipsed the next day by Tan Le. Tan is the head of San Francisco's Emotiv Systems, and her showpiece was a wireless headset called EPOC.

It turns the electrical traces of thought processes into input commands for a PC. Mind control and gesture-based interfaces? The desktop PC was going to have a tough time fighting off the torrent of new touchscreen tablets. Can it possibly remain relevant?

For a couple of days, journalists were shown around labs full of 3D printers and machines with ten giant steel fingers that could put a keyboard through a lifetime of torture in just a few weeks. The tour was rounded off with a demonstration of a holographic-type transparent display, hooked up to a webcam which followed a user's hand gestures to move windows around, shamelessly aping the computers in Minority Report.

It was a charmingly Heath Robinson device, complete with bare wires and Meccano-type struts, which wowed the crowd with its unexpected sophistication. Unfortunately, given the amount of work that had gone into this prototype and the creator's obvious pride, it wasn't destined to become Project Natal.

Natal will be launched on 10 November as Kinect, and is built using licensed technology from the Israeli company, PrimeSense.

Kinect for Windows

Microsoft isn't talking about Kinect for Windows yet – and indeed turned down a request to be interviewed for this feature about plans for desktop interaction in general. It's safe to conjecture that it wants to promote Kinect on the console for now.

There's a good chance that something similar will be available for the PC before long, though. As well as the inevitable clones which will spring up, Microsoft doesn't have complete control of Kinect.

PrimeSense is actively seeking ways to get its technology into other devices, and company VP Adi Berenson confirmed to Engadget.com that it has at least one set-top media player in the works, which was described as an 'HTPC', or Home Theatre PC.

That suggests some sort of x86-compatibility. This HTPC is likely to be a sealed unit, but PrimeSense's NITE software, which provides the gesture reading magic, runs on Windows and Linux. Even if there's no official Windows product for a while, it shouldn't be long before there are unofficial drivers for USB variants that are available.

With a Kinect-type device for the PC, it's entirely feasible that you could sit in front of a screen and wave your fingers into space to make letters appear, move a window or switch to the rocket launcher. If that's possible now, in five years time it'll be everywhere, right?

Multitouch

After all, look at how quickly multi-touch mousepads and phone screens have become ubiquitous after the launch of the iPhone; the human race must be crying out for an alternative to the keyboard and mouse.

Not according to those in the know. "As a Human Computer Interaction (HCI) researcher I tend to have a sort of love-hate relationship with the mouse," says Professor Scott Hudson of the HCI Institute at Carnegie Mellon University.

"The fact of the matter is that the mouse is an extremely good input device for what it does. If you are editing a document, working with a spreadsheet, or clicking on links on the web, you probably want to use a mouse for that because it does a really good job. In fact, you can show scientifically that for simple pointing tasks you are probably not going to get a whole lot better than a mouse in terms of basic performance."

The path of progress

Academics in the field of HCI can be a surprisingly conservative bunch, but the history of the field teaches caution. Gadgets such as the iPhone or Kinect don't spring fully formed from nowhere and push back the boundaries of what's possible overnight. It took over two decades for multi-touch tablets and screens to move beyond proof of concept and specialist use into mass production and consumer electronics.

For anyone who's not an HCI Researcher, the job title may suggest a working day that involves breakfast with HAL, a pair of augmented reality glasses and a some 'blue sky thinking' about anti-gravity operator chairs. This impression is probably due to the fact that the only time HCI hits the headlines is when something out of the ordinary is shown off or talked about in an academic journal.

Most of the challenges in HCI are far more prosaic. Inspired by Kinect, the iPad, EPOC, et al, I went in search of holograms and USB spinal taps, and found instead the unsung heroes who use eye-tracking technology to illustrate bad web design and make the internet a slightly less annoying place. You're far more likely to find people working on very practical projects than chasing supercool sci-fi dreams.

At City University's Interaction Lab in London, for example, projects include studying how people operate simple 3D games and hacking Wii-motes to turn a desk into a cheap collaborative touchscreen.

One input idea which has taken a long time to gestate is voice recognition. There are some devices, notably the iPhone and certain in-car sat navs, which have a reasonably usable voice control system, but City's Interaction Lab Manager, Raj Arvan explains why it's failed to take off on the desktop:

"Voice recognition applications are becoming more accustomed to picking up natural language and the way people speak, but they are limited culturally," he says. "That needs to be accounted for. You need to have the same level of language sophistication wherever a system is going to be deployed."

There's also no reason for a new technique to supplant an old one that works well. The purpose of design is not to replace something that's already working well," says Raj Arvan, "The keyboard and mouse do a good job.

"You could use voice recognition to augment them in small ways, say commands for printing or opening an email client, but they'd be supplementary to the core functions. That's how it starts off, then if in the future the next generation becomes more comfortable using dictation then they'll use it to write whole documents."

MS COURIER: Microsoft canned its two screen tablet, but Toshiba's Libretto is still due this year

This is good news for us, because it means that the home computer as we know it isn't going anywhere for a while. Next time you're wowed by a demonstration of augmented reality overlays or thought-sensitive controllers, watch Keiichi Matsudafor's excellent short film 'Augmented (hyper) Reality: Domestic Robocop' for a seminal lesson in why we should be wary of embracing new interfaces too quickly for our own good.

"I think in five years that Microsoft Windows will look, well… like Windows," says Carnegie Mellon's Hudson. "The graphical user interface that Windows embodies does a very good job at what it does and I don't see it going away any time soon or necessarily turning into anything else. But I think that's not the interesting question. The interesting question is what else will we see along side [Windows]?"

Get your supplements

This sentiment is echoed in the corporate strategies of Microsoft, Intel and Apple. It's best summed up by Microsoft's 'Three screens and the cloud' picture of harmony between the telephone, the PC system and the telly that CEO Steve Ballmer spoke about at the 2009 Consumer Electronic Show.

In the first half of the decade, everyone was competing to produce the single 'hub' device for the digital home. As a result there was a lot of pressure for the PC to evolve into a single 'convergence' unit with all manner of crap attached to it. Now there's an understanding that people don't want to replace the PC with one single device, but supplement it with other specialised boxes in the home.

C-SLATE: Work continues at Microsoft on the C-Slate, a display-based input pad

One of Intel's Consumer Experience Architects, Brian David Johnson, describes this using the image of watching TV while looking up information about the show on a laptop and at the same time tweeting about it through their phone. Each device has a specialism that doesn't necessarily need to be supplanted.

"People are very comfortable moving through their lives looking at different screens," he says, "It's not about the mobile phone killing the internet or the internet killing television and the PC going away … We need to understand that consumers' lives touch multiple products at any one time."

Hudson thinks this process of device proliferation, rather than convergence, has only just begun: "If I were to take a guess," he says, "I'd say that we will see an explosion of very small, inexpensive, and highly specialised devices. You can now buy for less than $1 a single chip with a computer in it that's much more powerful than the computer that was used in the lunar module and landed men on the Moon. There is a lot of potential in these devices that we haven't seen exploited yet."