Open source is quietly powering a virtual revolution in some countries

Equality through education

Sacatepéquez, Guatemala. You won’t find the village of El Rosario and its corrugated iron and breeze-block houses on any printed map. Ironically, you can find El Rosario on Google Maps but the village itself doesn’t have internet access. Such a luxury is a number of bus rides away and not a journey you’d want a child to take alone.

Reducing the educational limitations for kids who grow up in places like El Rosario requires breaking vicious cycles that are generations-old: “The kids that don’t finish primary school end up working in the fields with their fathers,” says Sandra Castro, a teacher at the local school, Escuela Nacional El Rosario. “Our desire is to change that.”

One non-profit educational technology organisation that’s helping to effect that change in El Rosario and all over the world is Learning Equality. It’s an organisation that uses open source software and low-cost hardware to bring quality education to offline communities in the remotest parts of the world – and it’s gearing up to release its second-generation educational platform, called Kolibri.

Just under half the world has no internet access, while for many others that do, access is expensive, unreliable, and often low bandwidth, says Jamie Alexandre, cofounder of Learning Equality. “It’s not that a country is completely offline, it’s just very limited […]. It might only be in some of the cities.”

Which is why the Kolibri platform is designed to exploit the internet wherever it can find it. “We can use the internet to seed the software and content,” says Alexandre. “Some person somewhere has to download the software, but they can leave it running for a couple of weeks to get the first version of the content or they might run it at night if it’s cheaper […]. Then they can copy it onto a USB key or preconfigured server and carry that to somewhere that doesn’t have any connectivity, clone it across multiple devices or set it up wherever it is as a hotspot device.

“In some cases schools have [internet] connectivity even if it’s intermittent or slow, but it’s enough to get the content over a longer period, and then they can run it as a local server. Now it’s accessible over the local network within a school or with a hotspot within a class. Then other client devices can connect to that local server without needing any internet connectivity.”

Khan do

Alexandre has a background in cognitive science with a PhD in the subject from the University of California. For the first few years of his PhD he was interested in the theory of how people learn, particularly languages, but shifted into more applied work building a language learning website, and then he had an opportunity to spend a summer working for Khan Academy as a software development intern.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

“I wanted to intern there as they were rising in the field of educational technology […] and I wanted to learn and apply some of my techniques,” says Alexandre. “A lot of what I was doing was working on their core platform, but I saw all this exciting material being developed, these new pedagogical ideas, and new approaches and tools to support teachers and students.”

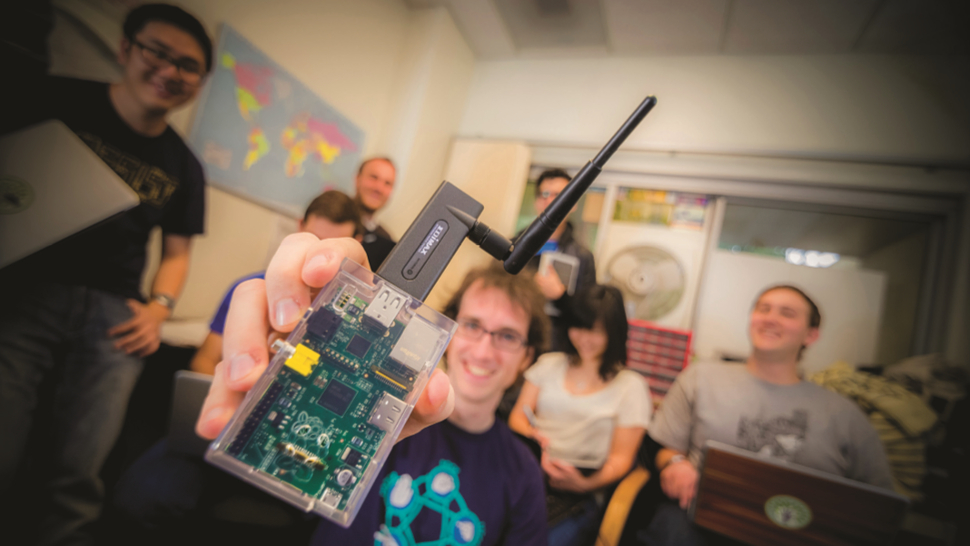

In a perfect triangulation, the Raspberry Pi launched in the same year and opened Alexandre’s mind to the possibilities: “Another intern and I were looking at it and saying: here at Khan Academy there’s all this amazing material, there’s this really, really low-cost device, low power and can be used in a diverse set of contexts even in places with limited infrastructure, connectivity or power. We can take all this cool stuff that’s happening at Khan Academy and we can squish it onto this Raspberry Pi, maybe that’s an opportunity to bring it to folks that would otherwise not have access.”

But it soon became clear that although the Pi was going to be the answer for some installations, the majority of the world needed an offline solution that could be used on many devices: “In 2012, two-thirds of the world was still offline,” says Alexandre. “So [KA Lite] started as a hack, an evening thing, and then we did a prototype, we demoed it and there was a lot of excitement and then I brought it back to grad school as I was still working on my PhD. That’s how KA Lite started.”

Let there be Lite

KA Lite duplicates the online educational experience of Khan Academy but for an offline setting, so pupils can access content, such as practical exercises and instructional videos. The initial version of KA Lite was announced on Reddit in December 2012. Alexandre felt KA Lite would get some initial interest and perhaps see folks wanting to collaborate, “but it turned out that people started deploying it immediately all over the world,” says Alexandre. Khan Academy linked to the project and it snowballed (as seen on an interactive map here).

What was a fairly early beta that didn’t have a lot of the planned functionality for wide-scale use was being adopted at a rapid pace. “It was in 60 countries within the first six months,” recalls Alexandre, and KA Lite’s architecture ended up being locked in because it had such an unexpected wide-scale adoption. The team were soon dealing with backwards compatibility as KA Lite now had a large, enthusiastic community to support.

Then the phone kept on ringing: “We started having conversations with UN agencies and the World Bank within months of starting out. It became very clear that there was a lot of need or demand, not some niche, but a huge critical global demand for high-quality educational resources in low resourced settings, [places with] limited internet, limited electricity and diverse, old hardware,” says Alexandre. So a group of students found themselves running a non-profit by the spring of 2013.

Top image credit: Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications

Chris Thornett is the Technology Content Manager at onebite, editor, writer and freelance tech journalist covering Linux and open source. Former editor of Linux User and Developer magazine.