What is a liquid lens? The tech that could revolutionize phone cameras explained

Find out how liquid lenses use fluid to focus faster

Lenses and liquids are generally best kept separate, yet the future of photography could lie in combining the two with, you guessed it, liquid lenses.

The average camera phone lens today is restricted to a fixed focal length. Adding versatility means either adding more lenses – or switching to a larger camera with adjustable optical elements.

Not so with liquid lenses: they use a small pocket of fluid instead of physical discs, changing shape to direct and focus light. They’re small, super-fast and sturdy, too. And they could change the world of smartphone photography.

Want to know more? Join us as we dive into the world of liquid lenses.

How do traditional lenses work?

Traditionally, the course of light through a camera lens is controlled by a series of polished optical elements. These curved discs – usually made from glass or perspex – are used to ‘bend’ light as it passes down the barrel. With the correct spacing between lens elements and the sensor, an image should arrive at a single fixed point, sharp and in focus.

In general terms, when a camera’s electric focus motor fires – or you manually twist the tube – the physical distance between those optical components changes. This in turn changes the focal length, bringing the image into focus on the sensor or, in the case of a zoom lens, altering the field of view – from wide-angle to telephoto.

As any owner of a DSLR or mirrorless camera will know, no single lens is fit for every situation. Some can cover fairly large zoom ranges, but they have to be sizable simply because of the space required to fit the optical elements inside. And if a lens doesn’t cover the focal length appropriate for a given scene, you’ll need to switch to different glass – as long as you have some stashed in your camera bag.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Just like prime lenses, most standard smartphone cameras feature a fixed focal length, thanks to their static optical elements. It’s rare to see genuine optical zoom on a smartphone, because it requires separation of these elements; even at microscopic levels, this is difficult to achieve within the slimline confines of modern mobile design. And that’s where liquid lenses come in.

How do liquid lenses work?

Imagine a water droplet on a leaf – the kind you often see captured on the pages of photography magazines. Just as this bead can refract natural light, so too can the fluid in a liquid lens guide light onto an imaging sensor.

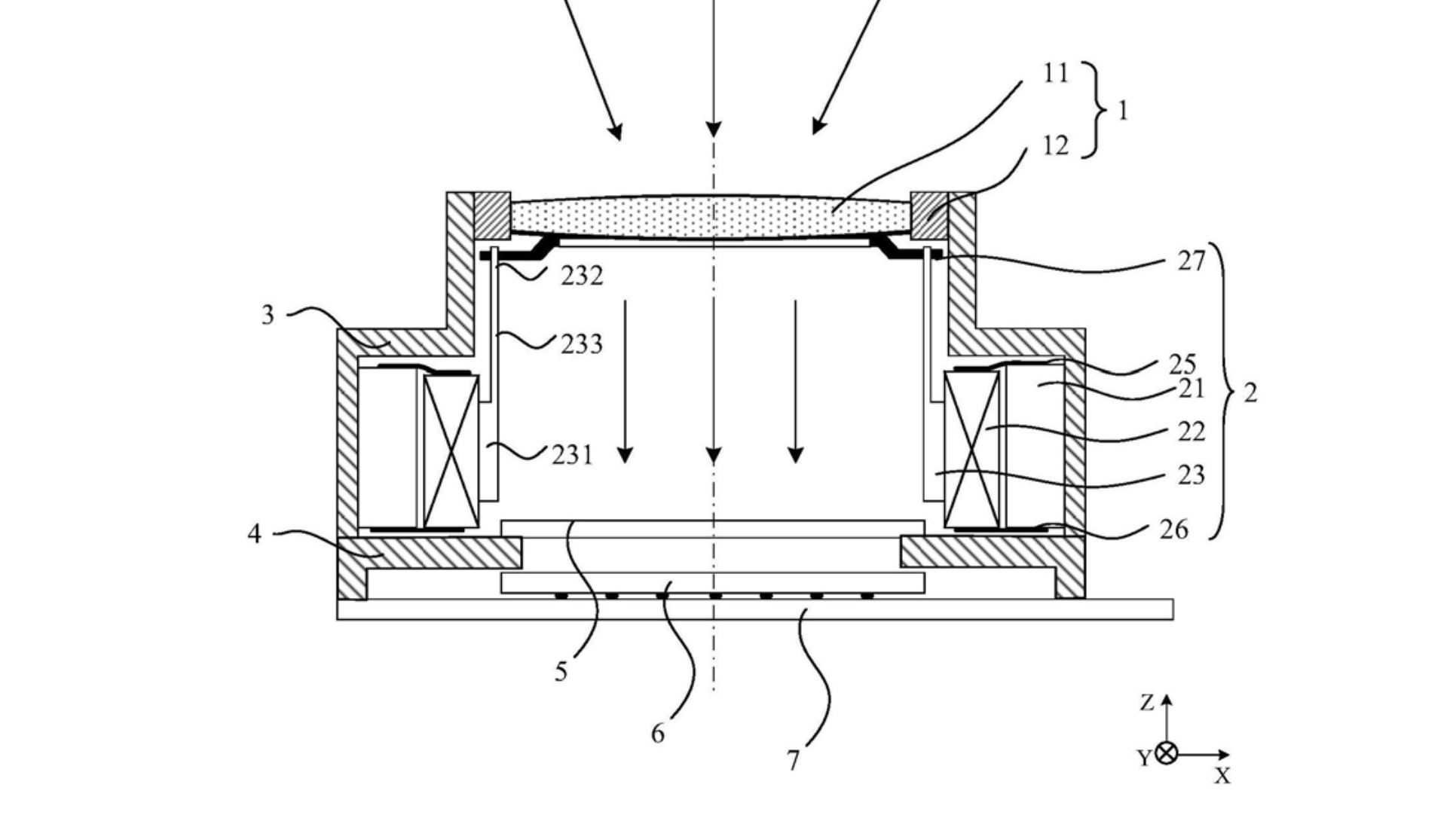

Most liquid lenses use no mechanical components. Instead, they contain a transparent fluid capsule. By applying pressure to part of this pod, its shape can be manipulated. Squashing or stretching it alters the trajectory of light passing through the optical-grade fluid – and therefore the focal length.

The liquid lens concept has been implemented in several ways, with different methods employed to exert pressure on the capsule. But the magic almost always happens when electricity is added.

One technique – known as ‘electrowetting’ – pairs water with a separate layer of non-conductive oil, which sit together in the lens. By applying voltage across the boundary between the two, the curvature – and so the refractive effect – can be altered in a fraction of a second. Corning’s Varioptic lenses use this technology.

Other solutions deploy alternative approaches to achieve the same result. Optotune’s focus-tunable lenses, for example, seal the optical liquid in a polymer membrane sac, which is then manipulated using electrical current.

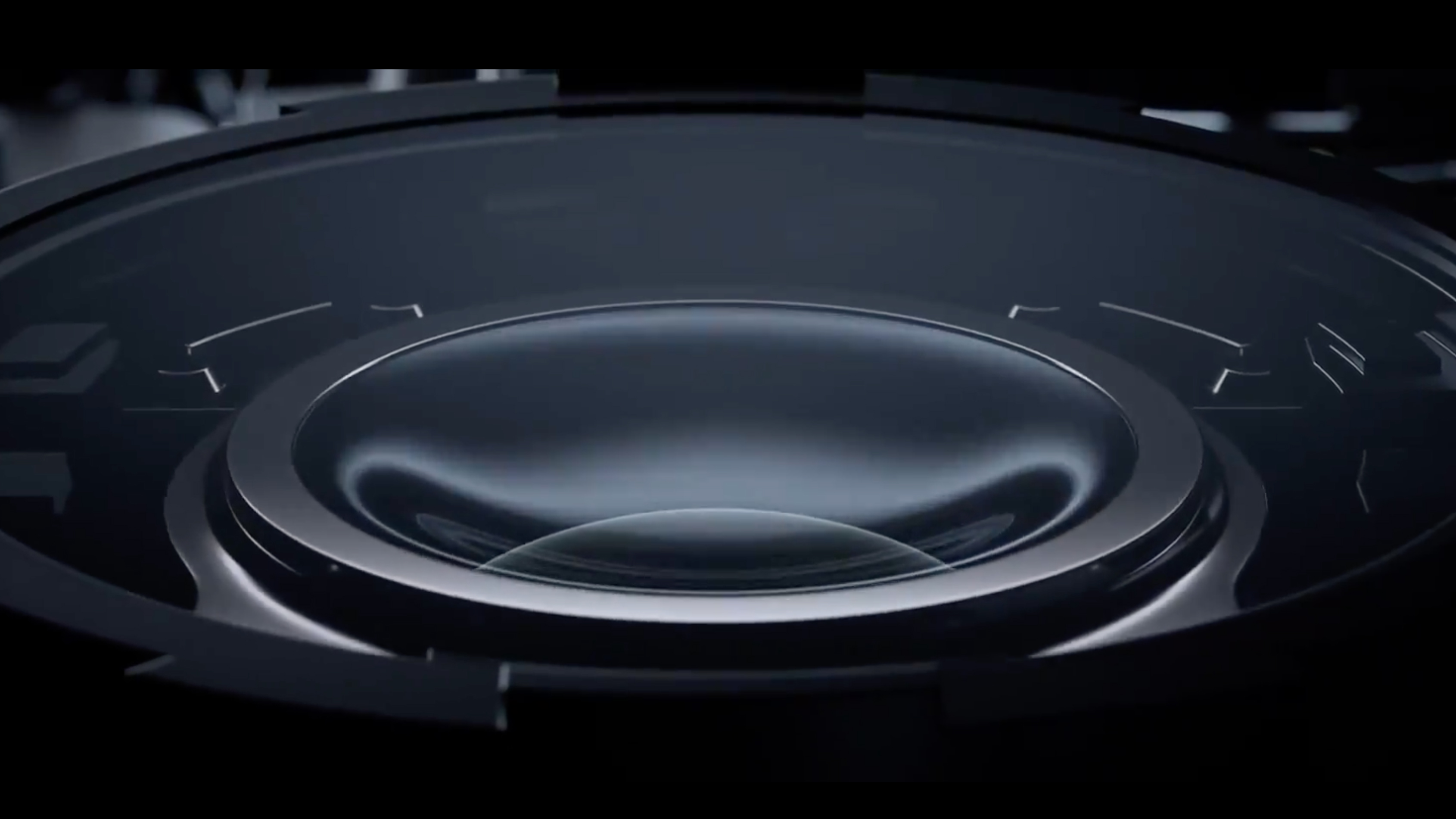

Xiaomi’s liquid lens tech, seen for the first time on the Xiaomi Mi Mix Fold (see above), takes a third route. The refractive fluid is contained in a film membrane, with a precision electric motor accurately deforming its radius to adjust focal length. The result is a single lens with a minimum focus distance of 3cm for macro shots and an optical zoom range of 3x – expanding to 30x with the help of some in-device digital trickery.

What are the advantages of liquid lens technology?

Liquid lenses offer several advantages over traditional lens technology. The main one is their ability to alter focal length without any moving mechanical parts. That means liquid lenses can be kept small and light.

Their tiny dimensions make them ideal for use on smartphones. So, too, does the ability to switch quickly between focal lengths, which could put an end to the multiple lenses now sprouting up on the back of smartphones. And if liquid tech can be integrated into the larger lenses used by DSLR and mirrorless cameras, your arsenal of bulky barrels could potentially be replaced by a single fluid solution.

Because most liquid lenses don’t use electric motors, they can normally focus far more rapidly than their mechanical cousins. The optical liquid inside reacts almost instantaneously to electrical current, which results in super-fast focus performance, plus pinpoint accuracy. The option to switch focal lengths in mere milliseconds could open up a world of possibilities for multi-talented photographers, too. Spotted a rare bird in the distance while shooting a flower in macro? No problem.

How Xiaomi’s approach compares isn’t yet clear: we haven’t been able to get hands-on with the China-only handset. Theory suggests a physical motor will be slower than a focus system which uses electrical current alone, but the liquid core will still deliver new focal length flexibility.

When liquid lenses use no mechanical components, durability is increased, as there are no moving parts to wear out or fail. Eliminating these elements also means liquid lenses consume minimal power, which should be good news for smartphone battery life. And whichever technique is used to manipulate the fluid cell, the liquid itself is generally less sensitive to vibration than a standard lens, which should result in improved optical image stabilization.

Like a standard smartphone lens, the physical aperture of a liquid lens doesn’t change. But liquid lenses offer a spectrum of focal lengths. Those two facts together should mean greater depth of field flexibility for mobile photographers, as well as improved low-light performance – aided by the low dispersion and high transmittance of light through the optical fluid.

Who is using liquid lenses now?

Thanks to their durability, tiny size and rapid reaction times, liquid lenses have been seen in industrial settings for several years.

The Edmund Optics M12, for example, is a lens recommended for use in production systems that require high-speed machine vision. This includes assembly lines, where objects of different sizes are inspected as they roll out of the plant. With all refocusing controlled by the liquid lens, the M12 is able to rapidly adjust to items as they pass beneath the sensor.

Despite their availability and potential advantages, liquid lenses have only just arrived on smartphones. Xiaomi’s folding Mi Mix Fold flagship – launched in April 2021 – is the first consumer handset to feature a liquid lens.

As above, Xiaomi’s system uses a high-precision electric motor to alter the capsule’s shape. At the time of writing, it’s the sole smartphone with a liquid lens – and it’s currently only available in China.

Will we see more liquid lenses?

While their size makes liquid lenses ideal for use in smartphones, it’s trickier to leverage the technology for larger camera formats.

Focus speed is just one aspect of a camera’s performance. Even with near-instant focal length adjustments on offer, pro photographers will still want the low-light skills and outright image quality offered by bigger sensors. That poses a problem: according to Edmund Optics, the largest liquid lens aperture is currently 16mm, which means it’s only suitable for use with sensors up to 1/1.8in.

While that’s fine for the sensors found in most compact cameras, it doesn’t come close to covering Micro Four Thirds or APS-C sensor sizes. Until the technology grows, liquid lenses are unlikely to replace traditional interchangeable glass. So it’s worth hanging onto your camera bag for the time being.

But it seems highly likely that liquid lenses will be deployed more widely in the smartphone market. If its patent filings are to be believed, Huawei already has plans to deploy the tech. Many predicted it would appear on the new Huawei P50 Pro powerhouse. It didn’t – but a liquid lens could yet show up on the P50 Pro+, which is rumored for launch later this year.

Perhaps understandably for an experimental imaging system, Xiaomi included standard cameras alongside the liquid lens on its Mi Mix Fold. Many manufacturers are likely to follow suit: in a smartphone market where multiple lenses are the norm, there’s a good chance you’ll see brands adding liquid lenses as one of many on their mobiles – at least until they understand the true capabilities of the technology.

Once the potential for liquid lenses is proven, though, it’s not far-fetched to suggest we may see a return to single lenses on future smartphones. If a single snapper is capable of switching quickly between focal lengths, zooming optically and resisting vibrations, why add more?

Current limitations mean larger liquid lenses are likely a long way off. But they’re already available in a form which fits most mobiles. Paired with the most powerful sensors yet seen in smartphones, the versatility of liquid lenses could revolutionize pocket photography – and sound the final death knell for compact cameras.

- These are the best photo editing apps you can download right now

For more than a decade, Chris has been finding and featuring the best kit you can carry. When he's not writing about his favourite things for Stuff, you'll find Chris field-testing the latest gear for TechRadar. From cameras to classic cars, he appreciates anything that gets better with age.