Here's how your phone is tracking you right now

Understanding how your phone uses sensors to keep tabs on you

Right now there's a good chance your phone is tracking your location, keeping tabs on your steps and recording any voice searches that you might make. And that's just the beginning.

Of course we all know that our phones can do far smarter things than we'll ever use them for and big tech companies make no secret of the fact that their products are packed full of a whole bevy of sensors.

So why are many of us surprised when we find out Google records every step we take? Or every voice search we make? Or Apple Health has been tracking our activity for months now when we already have a Fitbit to do that?

There's an irony here. We want our phones to be smaller, smarter and capable of doing more cool stuff than ever, and yet significant improvements in mobile tech mean everyone from big brands to small app developers could access data about everything we do just from our phones.

As more and more sensors are being packed into our phones there's never been a better time to explore what your handset is really tracking right now, which sensors are responsible and whether there's any reason to be concerned about it.

Which sensors are in your handset?

If we get back to basics, a sensor is a piece of tech that measures a physical quantity and converts it into a signal. This signal can then be used by an app or read by an individual.

Depending on what handset you have, it'll contain any number of different sensors.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The most obvious are all about movement. These include the accelerometer, for measuring movement and orientation, and the gyroscope, for measuring angular rotation across three axes and giving more accuracy to the accelerometer reading.

Location services are taken care of with a magnetometer for detecting magnetic North and some form of GPS chip or a related variant to plot your position on the map.

On top of this there are the more obvious ones, like a proximity sensor for recognising when you move your phone up to your face during a call, a microphone and a range of sensors within your phone's camera to ensure you take the best snaps.

There are also environmental sensors, which measure things like temperature, barometric pressure and light, although these are more commonly found in higher-end phones. These are used to do everything from tell you when your skin is getting hot through to boosting brightness levels in dark environments.

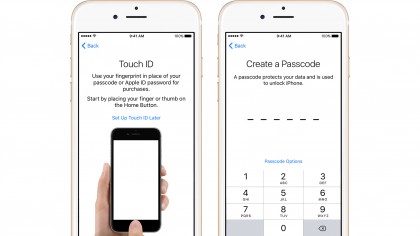

There are additional sensors out there too, as handsets like the iPhone 6S and Samsung Galaxy S7 also have their own fingerprint sensor.

The latter also goes further by packing a built-in heart rate monitor that comprises of both a red LED and Pulse Sensor. The Google Nexus 5 has a pedometer built-in, whereas other phones use data from a range of sensors to track steps - so every time you flicker your phone, something lights up inside to guess what you're up to.

Don't forget - most of the sensors are benign and helping you massively. The motion co-processor in the iPhone, for instance, can work how the phone is being used - is it on a desk, or in your pocket? - and use that information to decide whether to power on certain elements, crucially saving battery.

What are they tracking?

Here's where it gets more complicated. Sure, you have a bunch of sensors inside your phone. But figuring out what they can do, whether they're doing it right now and if you gave them permission to do it is a rather grey area and probably different for every user.

It's important to remember that the sensors themselves are just tools in the hardware, but it's how phone manufacturers or app developers tap into these sensors which we're interested in figuring out.

Gaurav Malik, Programme Leader and Senior Lecturer in computer Science at the University of East London said, "The number of sensors on your phone should not concern you, but the number of apps using that sensor data should."

He warns that we should be wary of "how the data is being used and also if there is any personal details being stored."

It's this tracking and subsequent storing of data which seems to have caused such upset over the past 12 months.

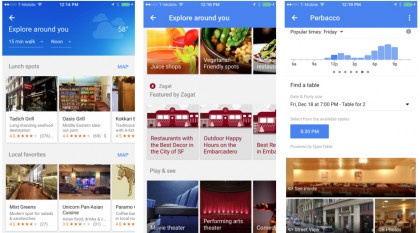

For instance, your whereabouts can be tracked with a lot of accuracy using a combination of your location-based sensors.

These can not only plot your position on a map, but in combination with an accelerometer they're able to paint a picture of where you've been over the past year or so too.

Google's Your Timeline feature made tech headlines when some users found out that the company had been keeping track of their location data and creating a creepy map of their whereabouts dating all the way back to near 2012.

Step tracking is similar. A few handsets have dedicated pedometer sensors, whereas others combine data from a number of different sources to track the steps you've taken throughout the day.

One example of how this data is used is to inform all of your third-party health apps how active you've been. But the likes of Apple Health collate all of this data too. So although you may be using a Fitbit, take a look inside Health on your iPhone and there's step tracking information there as well. Sure you may have approved it at some point, but did you know it was keeping such a close eye on your movement?

As more and more tech companies and apps aim to create personal assistants for our phones, the sensors within our microphones are becoming more important than ever.

This means voice tracking, analysing and recording tech wants to make sense of what you say to make our smart assistants more useful. But what many people don't realise is that Google stores your voice searches long after you've made them.

The thing is, when it comes to all of these sensors and the data they gather, it's relatively easy to delve into your settings and toggle different apps and services on and off, revoking access where you see fit.

Of course many people argue that something has been tracked without their permission. But as much as we don't want to admit it, the truth is that often we have given Apple, Google or an app permission to do something, we just didn't realise it because it's often not that straightforward.

We spoke to Mike Feibus, Principal Analyst at FeibusTech, about this problem and how many of us end up saying yes to permissions we don't mean to - either through negligence or just minsunderstandings.

He told us that although it's easy for companies to get us to say yes to stuff, it's not in their best interest moving forward - and it depends on the ilk of developer as to whether you should be really worried or not.

"No matter what permissions we agree to give an app, most of us assume there are boundaries you don't cross without explicitly asking if it's OK. It's no different than when we say "make yourself at home" to a visitor, we assume that they won't go poking around in our underwear drawer."

"There will be developers who continue to push the limits. But app developers who really want to know us – like Google or Cortana or Siri or Alexa inside Amazon's Echo – had better understand that they need to be trusted as a true personal assistance app."

Should we be worried about sensors and what they're up to?

The big question is whether we should really be feeding into surveillance paranoia and have reason to worry about the data that's being collected by the growing number of sensors in our phones.

Should we instead realise that some tech companies and apps might be sneaky and we should just become more aware of permissions ourselves?

Feibus told us that for the most part we shouldn't start smashing our phones or removing our batteries like Edward Snowden after 15 cups of coffee, because it's probably all about making money and irritating us with ads rather than nefarious tracking of our locations. He said:

"For the most part, those who watch us are in it for the money […] The most common thing going on in our phones is for marketing purposes. They'd like to understand where we go, what we like. Then the information feeds targeted ad campaigns."

In this way it's all down to personal preference. Some people are so used to being advertised to it might not bother them to find out their favourite supermarket might be buying their location data. Others would still be quite disturbed by that. Feibus agreed:

"There's a tendency for people to worry unless companies are specific about exactly what they intend to do with your data, and how they intend to protect it. Then people can make a decision on a case-by-case basis whether they want to participate."

Of course that doesn't mean there isn't scope for sensors to be used in more malicious ways that we'd never even know about until it's too late. For instance, a recent study made headlines that proved data from motion sensors could be used to read your PIN number.

But, just like protecting our credit cards as best we can, there's plenty we can do to stop fraud from happening — it's just never an absolute certainty. And that's how we should view the sensors in our phones, too.

If you wise up to the access you're granting apps and companies to the data that your sensors are collecting you should feel relatively safe and secure - and it's good to see Android's stopped offering a list of permissions when you download an app (which most of us never read) and asking for permissions the first time the app needs them.

A new map app will probably want access to your location services. Great! But if a flashlight app does, that should immediately ring alarm bells.

You should always be questioning whether a third party app is really built to do what it says it's going to do or whether it has ulterior motives.

The same goes for looking back through what currently has access to your sensors (head into your settings menu and find the list of applications in there to check), to make sure you didn't slip up in the past.

Malik agrees there's little genuine reason to be too concerned right now, assuming you don't mind companies selling stuff to you based on where you are. But he said that as more and more biometric sensors collect health data we might start facing issues around our private data being sold to the highest bidder.

He said, "As we start using sensors for more personal things like heartbeat and pulse, there is a risk the app, rather than the phone company, may share the data."

Right now your main concern should be whether you can control your location being sold to a restaurant or shopping mall for advertising purposes.

But as Malik suggest, this might soon be just the tip of the iceberg. As tech gets smarter, smaller and cheaper it's going to become more challenging to separate the data you don't mind being stored and shared from the stuff you really don't want getting into the wrong hands - so be vigilant with all the permissions you grant, and make sure you trust every piece of software you install onto your phone.

Becca is a contributor to TechRadar, a freelance journalist and author. She’s been writing about consumer tech and popular science for more than ten years, covering all kinds of topics, including why robots have eyes and whether we’ll experience the overview effect one day. She’s particularly interested in VR/AR, wearables, digital health, space tech and chatting to experts and academics about the future. She’s contributed to TechRadar, T3, Wired, New Scientist, The Guardian, Inverse and many more. Her first book, Screen Time, came out in January 2021 with Bonnier Books. She loves science-fiction, brutalist architecture, and spending too much time floating through space in virtual reality.